Common Field Farming Alan Payne and Jonathan Parkhouse, June 2021

|

The isolated farmsteads typical of the early Saxon period were no longer the sole basis of occupation by the middle Saxon period. Clusters of close-living residences began to arise, grouped into centralised settlements. This is often characterised as the "nucleation" (concentration) of residential properties and support buildings which, in later periods, were called villages. The changes were not universal, or synchronous and settlement shift occurred over a very long period of time and continued after the Norman conquest.

There were probably many different reasons for this development: the rise of aristocratic and royal power, the emergence of long-distance trade networks (although perhaps less evident in Wessex than further east), the development of towns, minsters, sites of production, and growth of a monetary economy. In addition, there were major changes in agriculture which some historians have called "a revolution". We can see how this new farming system merged different elements - large field areas cleared of scrub, a commitment by residents to work together, and the division of cultivated land into strips cultivated by different residents. Together these are called "common field farming". |

Evolution of the System

Collaborative farming in open fields (without walls or hedges) came into operation possibly in the late Saxon period, running alongside traditional land ownership.[1] This would have been a major change in society and would have taken considerable planning and greater centralised control. Its origins are not well-understood but we can see some origins in the way that society became stratified in the reigns of Ine and Alfred with the rise of a landholding elite, rather than the old ingas family structure. Alfred’s Laws envisage a very stratified society based on a person’s wergild (the value which had to be paid for causing a person’s death), composed of: noble (wergild 1,200 shillings), geneat (member of noble’s household 600 shillings), ceorl (lowest status of Anglo-Saxon freeman 200 shillings) and slaves (varied).

Collaborative farming in open fields (without walls or hedges) came into operation possibly in the late Saxon period, running alongside traditional land ownership.[1] This would have been a major change in society and would have taken considerable planning and greater centralised control. Its origins are not well-understood but we can see some origins in the way that society became stratified in the reigns of Ine and Alfred with the rise of a landholding elite, rather than the old ingas family structure. Alfred’s Laws envisage a very stratified society based on a person’s wergild (the value which had to be paid for causing a person’s death), composed of: noble (wergild 1,200 shillings), geneat (member of noble’s household 600 shillings), ceorl (lowest status of Anglo-Saxon freeman 200 shillings) and slaves (varied).

|

Glossary bordarii = cottager bretwalda = overlord ceorl = free commoner, often peasant coliberti = freed slave coseez = royal cottager cottar = tenant with perhaps 5 acres ealdorman = lord from ethel (noble) gebur = freeman owning plough and team geneat = member of noble’s household gesith = royal companion servi = slave thegn = lord villani = small tenant farmers holding perhaps 30 acres wergild = value of dead person payable to family |

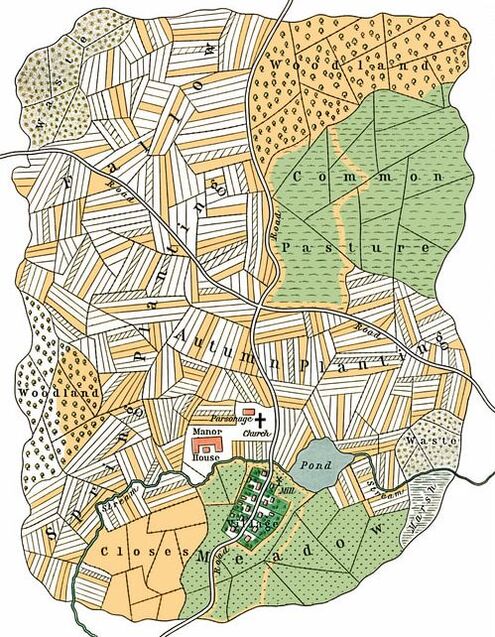

Fundamental changes were evident in Saxon society at a similar time to the evolution of open field farming. The

open fields were farmed communally by residents according to strict instructions as to usage in which all residents were required to plant the same crop which they sowed and reaped together. Some lords rose in status and some ceorls declined, eventually being reduced to the status of serfs (peasants). These serfs were obliged to working on the lord’s demesne land for customary days, often Mondays and three days a week at harvest time. In return for this service they were allowed to keep the harvest from other land such as farm strips in the open fields. This open field farming encouraged topographical change including nucleated villages and a court system to adjudicate land matters. Manorial courts were usually operated by the lord’s reeve (steward, sometimes head tenant) and had to decide crop rotation, land disputes, succession and tenancies. |

Local Circumstances

In the Cotswolds, two open fields generally prevailed (one farmed, the other fallow) but at Castle Combe there is evidence of a three-field system.[2] Elsewhere in later Saxon centuries, the two-field system evolved into three-field rotation - one field planted with winter wheat, another with spring barley, and the third left fallow and fertilised with animal manure or marl (silt) or lime. Some late medieval fields were laid out in a very precise way using a measuring pole or perch 16½ feet long, divided into areas 40 poles long by 4 poles broad, which equated to 220 yards long by 22 yards broad, making an area of 4,840 yards, exactly an acre.[3] But there appear to have been local variations in the way the fields were laid out, not least in local variants of the rod length with a 'short' perch of 15 feet in central and eastern England, and a 'long' perch of 18 feet in Wessex.

In some areas of England (particularly the Midlands) fields were ploughed communally in long narrow strips because the plough with its team of 8 oxen was cumbersome to turn, making it easier to cultivate a long, straight strip of land amounting to an acre. The separation of the fields is called a headfodland (headland), caused by the soil thrown up where oxen turned at the end of each straight furlong (220 yards). Each resident held individual strips (selions) scattered all over the area to ensure equality when only one field was planted and the other left fallow. But this doesn’t appear to be the basic field shape in Box.

In the Cotswolds, two open fields generally prevailed (one farmed, the other fallow) but at Castle Combe there is evidence of a three-field system.[2] Elsewhere in later Saxon centuries, the two-field system evolved into three-field rotation - one field planted with winter wheat, another with spring barley, and the third left fallow and fertilised with animal manure or marl (silt) or lime. Some late medieval fields were laid out in a very precise way using a measuring pole or perch 16½ feet long, divided into areas 40 poles long by 4 poles broad, which equated to 220 yards long by 22 yards broad, making an area of 4,840 yards, exactly an acre.[3] But there appear to have been local variations in the way the fields were laid out, not least in local variants of the rod length with a 'short' perch of 15 feet in central and eastern England, and a 'long' perch of 18 feet in Wessex.

In some areas of England (particularly the Midlands) fields were ploughed communally in long narrow strips because the plough with its team of 8 oxen was cumbersome to turn, making it easier to cultivate a long, straight strip of land amounting to an acre. The separation of the fields is called a headfodland (headland), caused by the soil thrown up where oxen turned at the end of each straight furlong (220 yards). Each resident held individual strips (selions) scattered all over the area to ensure equality when only one field was planted and the other left fallow. But this doesn’t appear to be the basic field shape in Box.

Open Fields in Box

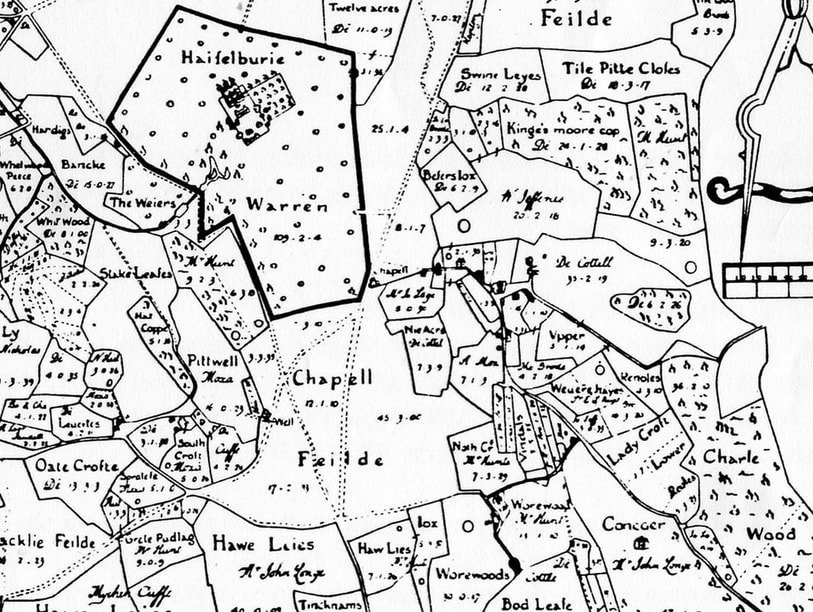

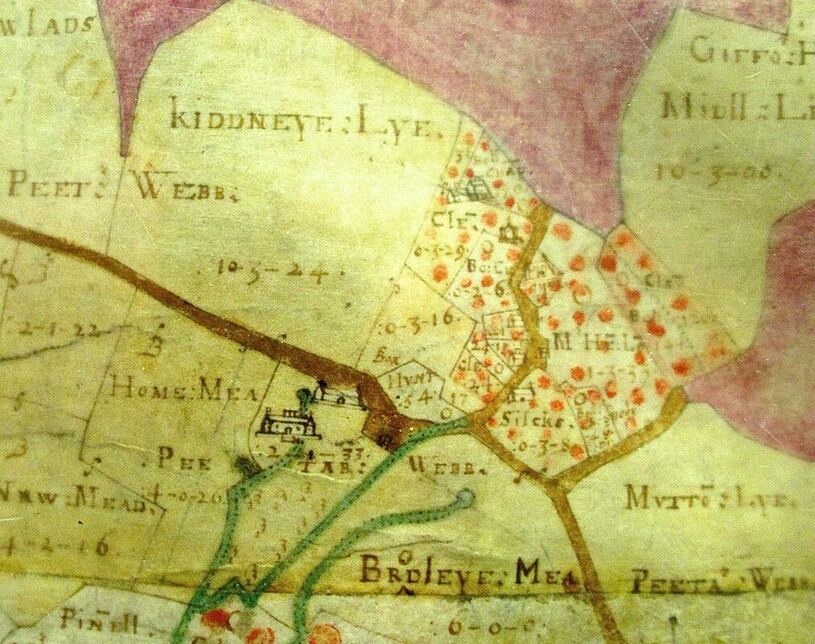

In the village, we are fortunate in having the Allen maps which give us a snapshot of what remained of our open fields at the start of the seventeenth century. Allen’s 1630 map shows two large open fields, called Box Fields: one of 38 acres, the other of 92 acres, divided by an embankment. To the north was a field called Bar Yeate, (a gated bridle-road that ran through the field), the name still remembered as Bargates. Possibly this was originally part of a central pathway into the fields but by the time of Allen’s map had become the boundary of the field.[4] A good view of these open fields is from the footpath to the north of Hazelbury Manor, where the path gives access to the centre of a large open field, still arable, undivided and exposed to whatever the weather throws at it.

Box’s Saxon fields are much more complex than classic open fields not least because of the predominance of animal husbandry in the area. In the west of the village was a field called Stichinges (a small piece of land) indicating it was unsuitable for arable.

In the 1840 tithe map there are several fields called leaze indicating that they were land not tilled, in other words pasture.[5] The fields include Swin(e) Leaze referring to grazing for pigs (ref 480). Sometimes usage may have varied, hence the oxymoron Oat Leaze (ref 146), part of a larger field called Mutton Ley.[6]

In the village, we are fortunate in having the Allen maps which give us a snapshot of what remained of our open fields at the start of the seventeenth century. Allen’s 1630 map shows two large open fields, called Box Fields: one of 38 acres, the other of 92 acres, divided by an embankment. To the north was a field called Bar Yeate, (a gated bridle-road that ran through the field), the name still remembered as Bargates. Possibly this was originally part of a central pathway into the fields but by the time of Allen’s map had become the boundary of the field.[4] A good view of these open fields is from the footpath to the north of Hazelbury Manor, where the path gives access to the centre of a large open field, still arable, undivided and exposed to whatever the weather throws at it.

Box’s Saxon fields are much more complex than classic open fields not least because of the predominance of animal husbandry in the area. In the west of the village was a field called Stichinges (a small piece of land) indicating it was unsuitable for arable.

In the 1840 tithe map there are several fields called leaze indicating that they were land not tilled, in other words pasture.[5] The fields include Swin(e) Leaze referring to grazing for pigs (ref 480). Sometimes usage may have varied, hence the oxymoron Oat Leaze (ref 146), part of a larger field called Mutton Ley.[6]

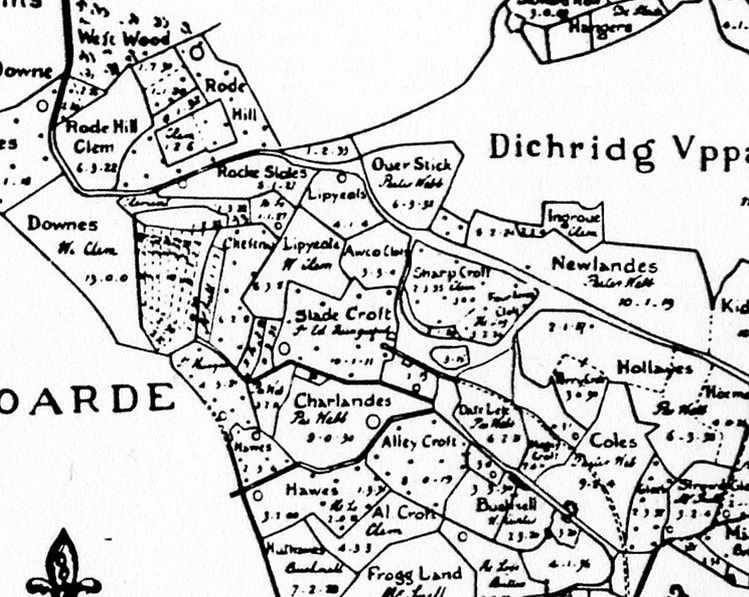

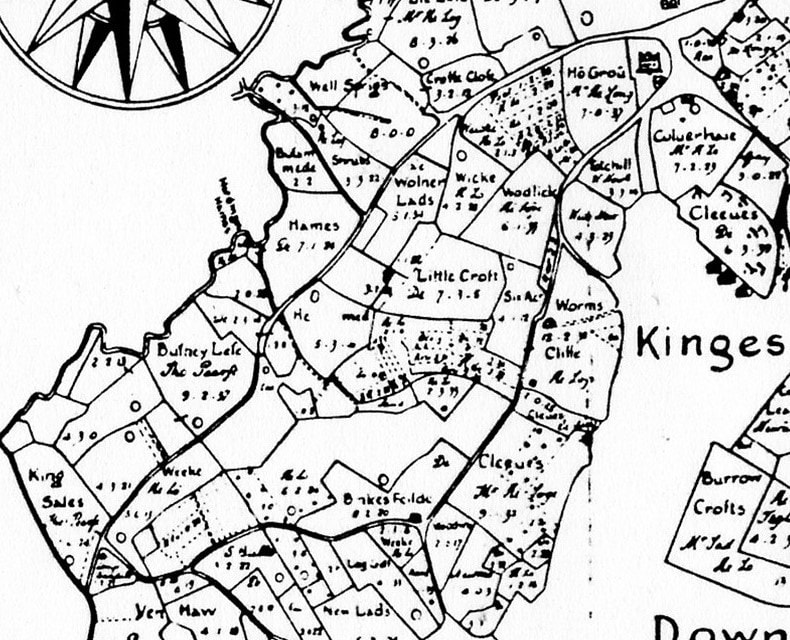

Looking at Allen’s 1630 map, we see a few reasonably long strips, but more strips which are relatively short and fat without the classic ridge and furrow with a reverse-S form. As well as those close to the open fields, strips exist throughout the area at Alcombe, Box Hill, Middle Hill, Ashley, Henley and Kingsdown. There is some (very modest) modern evidence for strip fields in the area of calcareous grassland at Wadswick Common (sometimes called Hazelbury Common), visible after the grass is cut in the early autumn; one can see a few of the strips shown on Abraham Allen's 1626 plan of Chapel Field, of which this area was a part. A couple of the paths crossing the common follow the edges of the strips, which here are long and thin.

Open Fields in the Hamlets

As well as the common fields in the centre of Box, there is evidence in several other areas, particularly at Ditteridge. Here there are two fields: Dichridg Uppar Feilde comprising 111 acres, 0 roods, 22 perches, the largest field in the area, and Dichridg Low Feilde of 67 acres, 2 roods, 17 perches. The fields were probably larger than those in Allen’s map because areas on the periphery have been enclosed, one such called Ingrove. Another field marked on Allen’s maps, Tile Pitte Fielde, was also open and has its own plan (in which it is named Tile Quarr Feylde). Separate plans also exist for Chapell Feilde, Blackley Field and Ditteridge. There may once have been a separate map for Box fields, too.

Ditteridge is an interesting administrative area. Whilst the main block of the landholding seems to have been in the north of the present Box parish, there are many other small blocks of land which belonged to Ditteridge, spread throughout Box parish. By the time of the tithe apportionment in 1840 some of these blocks did not correspond with the boundaries of the fields within which they were situated and we may be looking at perhaps just a few strips in the open fields which had been incorporated into the parish of Ditteridge. Does this imply that originally Ditteridge had been carved out of a larger entity, or the estate of an owner who managed to build up a demesne spread all over the common fields? Or is there some other explanation?

As well as the common fields in the centre of Box, there is evidence in several other areas, particularly at Ditteridge. Here there are two fields: Dichridg Uppar Feilde comprising 111 acres, 0 roods, 22 perches, the largest field in the area, and Dichridg Low Feilde of 67 acres, 2 roods, 17 perches. The fields were probably larger than those in Allen’s map because areas on the periphery have been enclosed, one such called Ingrove. Another field marked on Allen’s maps, Tile Pitte Fielde, was also open and has its own plan (in which it is named Tile Quarr Feylde). Separate plans also exist for Chapell Feilde, Blackley Field and Ditteridge. There may once have been a separate map for Box fields, too.

Ditteridge is an interesting administrative area. Whilst the main block of the landholding seems to have been in the north of the present Box parish, there are many other small blocks of land which belonged to Ditteridge, spread throughout Box parish. By the time of the tithe apportionment in 1840 some of these blocks did not correspond with the boundaries of the fields within which they were situated and we may be looking at perhaps just a few strips in the open fields which had been incorporated into the parish of Ditteridge. Does this imply that originally Ditteridge had been carved out of a larger entity, or the estate of an owner who managed to build up a demesne spread all over the common fields? Or is there some other explanation?

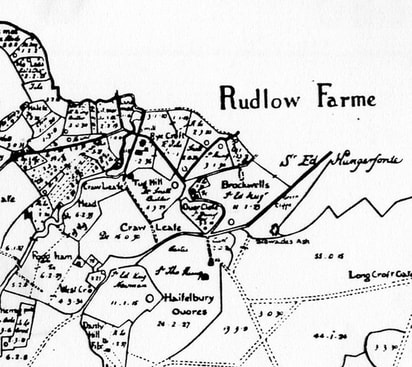

Field strips are shown in Allen’s 1630 map as dotted lines (maps courtesy Wiltshire History Centre)

Above Left: Alcombe, Above Right: Henley, Below Left: Ashley and Kingsdown Below Right: Rudloe

Above Left: Alcombe, Above Right: Henley, Below Left: Ashley and Kingsdown Below Right: Rudloe

We need to mention another singular item in the Allen maps which has attracted considerable speculation from historians, the location of the Oulde Church at Hazelbury. On the map, the site appears to be in the middle of open fields, perhaps left isolated when the villagers gravitated towards a nucleated centre closer to the By Brook. Evidence of considerable stone remains have been found in a field close to the air shaft and woods, near Woodland Adventurers, Quarry Hill but these have not been investigated further, so we have no identification or dating which is reliable.

Finding Evidence of Settlement in Early Medieval Box

The present Box village is highly centralised but we know that much of the residential area was developed in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Allen maps of the early 1600s also show a nucleated village – albeit much smaller - centred on the church and the Market Place. However, we don't know when this nucleation took place or how the settlement pattern changed, as it will have done, over several hundred years. It is hard to identify settlement in the area even by the time of Domesday Book, which has five entries for our area which are difficult, perhaps impossible, to locate precisely.

There haven’t been any finds of Saxon or Viking coins or pottery in Box to help identify an early medieval settlement. This isn’t indicative as not many finds have been made in nearby locations. The nearest find was at Slaughterford in 1957 when a single coin of King Egbert was discovered along with later coins of George II.[7] The Saxon coin has the king’s name Ecgbeorht and that of the moneyer who minted it Tidbearht at Canterbury. Two coins minted at Bath in the reign of Edward the Elder (king 899 to 924) have been found in hoards in other parts of the country and a hoard of fifty silver pennies dated about 955 was found in Bath in the grounds of Abbey House in a wooden box but no reason for their burial has emerged.[8] The use of coinage became a significant factor in Saxon commerce, not national specie as we are accustomed to but local moneyers, authorised to produce coinage and obliged to buy their dies from the king who regarded this as another income stream.

The present Box village is highly centralised but we know that much of the residential area was developed in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Allen maps of the early 1600s also show a nucleated village – albeit much smaller - centred on the church and the Market Place. However, we don't know when this nucleation took place or how the settlement pattern changed, as it will have done, over several hundred years. It is hard to identify settlement in the area even by the time of Domesday Book, which has five entries for our area which are difficult, perhaps impossible, to locate precisely.

There haven’t been any finds of Saxon or Viking coins or pottery in Box to help identify an early medieval settlement. This isn’t indicative as not many finds have been made in nearby locations. The nearest find was at Slaughterford in 1957 when a single coin of King Egbert was discovered along with later coins of George II.[7] The Saxon coin has the king’s name Ecgbeorht and that of the moneyer who minted it Tidbearht at Canterbury. Two coins minted at Bath in the reign of Edward the Elder (king 899 to 924) have been found in hoards in other parts of the country and a hoard of fifty silver pennies dated about 955 was found in Bath in the grounds of Abbey House in a wooden box but no reason for their burial has emerged.[8] The use of coinage became a significant factor in Saxon commerce, not national specie as we are accustomed to but local moneyers, authorised to produce coinage and obliged to buy their dies from the king who regarded this as another income stream.

Conclusion

Obviously, a village developed in the centre of Box at some time but we don’t know when or why this happened and the possibility remains that this occurred slowly in the later middle ages. The use of geometrically precise grids for laying out topography and field areas seems to have been prevalent in Wessex between AD 600-800 in monastic situations and again between about AD 940-1020 in a wider range of circumstances. The issue is important because it is likely that the same units for laying out open fields would be used for laying out settlements themselves, enabling us to determine the origins of Box village.

The earliest evidence we have is the Allen map which shows a fieldscape, already greatly altered by piecemeal enclosure and by the amalgamation of many of the strips. What is clear is that Box’s open fields were extensive, and may once have covered the majority of what is now Box parish. What we do not have is any indication of the date at which the open fields came into being, whether this change was a single planned operation or a more intermittent process. Any conclusion about dating remains uncertain and could be entirely post-conquest perhaps in the mid- or late- 1200s.

Obviously, a village developed in the centre of Box at some time but we don’t know when or why this happened and the possibility remains that this occurred slowly in the later middle ages. The use of geometrically precise grids for laying out topography and field areas seems to have been prevalent in Wessex between AD 600-800 in monastic situations and again between about AD 940-1020 in a wider range of circumstances. The issue is important because it is likely that the same units for laying out open fields would be used for laying out settlements themselves, enabling us to determine the origins of Box village.

The earliest evidence we have is the Allen map which shows a fieldscape, already greatly altered by piecemeal enclosure and by the amalgamation of many of the strips. What is clear is that Box’s open fields were extensive, and may once have covered the majority of what is now Box parish. What we do not have is any indication of the date at which the open fields came into being, whether this change was a single planned operation or a more intermittent process. Any conclusion about dating remains uncertain and could be entirely post-conquest perhaps in the mid- or late- 1200s.

References

[1] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.269

[2] John Hare, A Prospering Society, 2011, University of Hertfordshire, p.15

[3] WE Tate, The English Village Community, 1967, The Camelot Press, p.36

[4] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.127

[5] The word is cognate with Old Saxon lēsa (meadow)

[6] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.93

[7] www.britnumsoc.org/publications/Digital%20BNJ/pdfs/1955_BNJ_28_35.pdf

[8] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.108

[1] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.269

[2] John Hare, A Prospering Society, 2011, University of Hertfordshire, p.15

[3] WE Tate, The English Village Community, 1967, The Camelot Press, p.36

[4] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.127

[5] The word is cognate with Old Saxon lēsa (meadow)

[6] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.93

[7] www.britnumsoc.org/publications/Digital%20BNJ/pdfs/1955_BNJ_28_35.pdf

[8] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.108