Middle- and Working-Classes, 1870-1920

Alan Payne May 2015 Story of class struggle in late Victorian Box

Alan Payne May 2015 Story of class struggle in late Victorian Box

It is not possible to talk about late Victorian society without mentioning the rise of the middle class and the common shared culture they developed. We might ridicule some of their pretensions now but we can't ignore their impact because they created our standards and it is their status to which we now aspire as normal. But we should not deny the division created when Box people split into hierarchical layers who rarely mixed socially and who connected at work only as employer and employee.

The concept of class goes back to the early 1800s and is usually associated with industrialisation. According to the historian EP Thompson, the working class was established by 1832.[1] However, the form that class took varied over time. The concept developed significantly after 1870 as people tried to come to terms with a host of social changes. One traditional view of class (upper, middle and working class) gives a structure which never existed in Box in practice. Others have divided people into two sorts: those who owned property and ruled; and those who rented and were employed, which has merit in highlighting the importance of the home.

Thompson argued that class occurred when a group of people have a common sense of identity in relation to others and did things together to express and support the interests of their fellows. He argued that, ultimately, class centred on access to the means of production, the manufactories, that we have written about elsewhere in this issue. It was these people who created wealth in the village and owned the factories who were Box's middle class; and the people they employed who can be identified as working class. In this article we look at people in Box from contemporary photographs to illustrate the rise of the middle class in a rapidly changing world between 1870 and 1920.

The concept of class goes back to the early 1800s and is usually associated with industrialisation. According to the historian EP Thompson, the working class was established by 1832.[1] However, the form that class took varied over time. The concept developed significantly after 1870 as people tried to come to terms with a host of social changes. One traditional view of class (upper, middle and working class) gives a structure which never existed in Box in practice. Others have divided people into two sorts: those who owned property and ruled; and those who rented and were employed, which has merit in highlighting the importance of the home.

Thompson argued that class occurred when a group of people have a common sense of identity in relation to others and did things together to express and support the interests of their fellows. He argued that, ultimately, class centred on access to the means of production, the manufactories, that we have written about elsewhere in this issue. It was these people who created wealth in the village and owned the factories who were Box's middle class; and the people they employed who can be identified as working class. In this article we look at people in Box from contemporary photographs to illustrate the rise of the middle class in a rapidly changing world between 1870 and 1920.

Social Division in Box

We can see clearly the rise of the middle classes in Box. The old order shifted away from the old established families (like the Northeys, lords of the manor) and away from the highly monied families (the Pictors, who owned many quarries; and the Horlocks at Box House). Their authority was determined by an unchanging caste system, based on birth and pre-existing status, and was swept away when England moved from the Georgian to Victorian periods.

Class divisions arose out of the individual effort of a few Box families. The new aspiring middle classes had themselves previously been quarry employees who invested in property, domestic and manufacturing, which they occupied and personally controlled. They established family connections throughout the village: the Vezey, Pinchin, Lambert, Browning, Perren, Richards and similar families all inter-married. These families were in control of their economic destiny through running their own businesses and they distributed their own kind of individual philanthropy in the village through the clubs and organisations which evolved at this time.

Below them came the lower middle class: those who had secure jobs or were important tradesmen. These people were employees of the railway and the Post Office, farm and quarry managers, clerks (always men), traders and shop owners. Often they were the smaller shopkeepers in the Market Place and the shops which arose in the hamlets. Usually they rented their homes and business premises, sometimes from the great Northey estate which monopolised large parts of the village before 1919.

By the time the Great War started in 1914, Box School on the London Road had been in existence for forty years. But education did not offer opportunity to all in Box and its success was only partial. In 1911 there were 539 individual families listed in the Box and Ditteridge census. Of these, an amazing number (162 of household heads, equivalent to 30% of families) were engaged in the quarrying industry, despite the fact that the quarry trade was already plunging into serious decline. Along with over-reliance on quarrying, male employment in the area was concentrated on labouring. Farm employees, domestic gardeners, carters and council road repairers totalled 106 households (nearly 20%).

These workers were not the largest group, however. This was the position of married women, whose domestic duties were all-consuming in a period before washing machines, refrigerators or domestic water supply. They were domestics who bore unwanted numbers of children in an age before the pill, often very poorly educated.

We are hard pressed to see written or visual evidence of the lives and conditions of the working class. Partly this is because workers often lacked literacy and rarely had access to photography. Perhaps we should say these were conspicuous by their absence. Workers didn't challenge the existing order by joining a trades union, nor did they cause industrial strikes or disobedience. Many of the working class in Box were not industrialised working class. We can epitomise them as sub-contract workers in the quarry trade, often working on piece-rates for a family gang-master (foreman or overseer), usually father or uncle. These were the Dancey, Pinnock, Hancock and similar families.[2]

Forces of Change

Social change affected all aspects of late Victorian life in Box: church, local politics, leisure and lifestyle. It was largely caused by a shift in wealth and local influence. The paternalism of the squire and the church gave way when challenged by the rising middle class. The aspiring class were given considerable local power through changes in the franchise (particlularly Disraeli's 1867 Parliamentary Reform Act and the 1884 Act which opened voting to certain tenants rather than property owners); their patronage of local clubs and associations (cricket club, scouts, badminton); and the creation of devolved local government through the county, district and parish councils acts in 1888 and 1894. It enabled them to overrule the wishes of the lord of the manor (which they did over common land rights) and to distribute their own kind of non-sectarian patronage.

In one sense the middle classes created class division. It was part of their attempt to establish themselves and to differentiate their new status from their past. They were so successful that many of their attitudes have been absorbed into our modern life and we imagine their attitudes were always the norm.

We can see clearly the rise of the middle classes in Box. The old order shifted away from the old established families (like the Northeys, lords of the manor) and away from the highly monied families (the Pictors, who owned many quarries; and the Horlocks at Box House). Their authority was determined by an unchanging caste system, based on birth and pre-existing status, and was swept away when England moved from the Georgian to Victorian periods.

Class divisions arose out of the individual effort of a few Box families. The new aspiring middle classes had themselves previously been quarry employees who invested in property, domestic and manufacturing, which they occupied and personally controlled. They established family connections throughout the village: the Vezey, Pinchin, Lambert, Browning, Perren, Richards and similar families all inter-married. These families were in control of their economic destiny through running their own businesses and they distributed their own kind of individual philanthropy in the village through the clubs and organisations which evolved at this time.

Below them came the lower middle class: those who had secure jobs or were important tradesmen. These people were employees of the railway and the Post Office, farm and quarry managers, clerks (always men), traders and shop owners. Often they were the smaller shopkeepers in the Market Place and the shops which arose in the hamlets. Usually they rented their homes and business premises, sometimes from the great Northey estate which monopolised large parts of the village before 1919.

By the time the Great War started in 1914, Box School on the London Road had been in existence for forty years. But education did not offer opportunity to all in Box and its success was only partial. In 1911 there were 539 individual families listed in the Box and Ditteridge census. Of these, an amazing number (162 of household heads, equivalent to 30% of families) were engaged in the quarrying industry, despite the fact that the quarry trade was already plunging into serious decline. Along with over-reliance on quarrying, male employment in the area was concentrated on labouring. Farm employees, domestic gardeners, carters and council road repairers totalled 106 households (nearly 20%).

These workers were not the largest group, however. This was the position of married women, whose domestic duties were all-consuming in a period before washing machines, refrigerators or domestic water supply. They were domestics who bore unwanted numbers of children in an age before the pill, often very poorly educated.

We are hard pressed to see written or visual evidence of the lives and conditions of the working class. Partly this is because workers often lacked literacy and rarely had access to photography. Perhaps we should say these were conspicuous by their absence. Workers didn't challenge the existing order by joining a trades union, nor did they cause industrial strikes or disobedience. Many of the working class in Box were not industrialised working class. We can epitomise them as sub-contract workers in the quarry trade, often working on piece-rates for a family gang-master (foreman or overseer), usually father or uncle. These were the Dancey, Pinnock, Hancock and similar families.[2]

Forces of Change

Social change affected all aspects of late Victorian life in Box: church, local politics, leisure and lifestyle. It was largely caused by a shift in wealth and local influence. The paternalism of the squire and the church gave way when challenged by the rising middle class. The aspiring class were given considerable local power through changes in the franchise (particlularly Disraeli's 1867 Parliamentary Reform Act and the 1884 Act which opened voting to certain tenants rather than property owners); their patronage of local clubs and associations (cricket club, scouts, badminton); and the creation of devolved local government through the county, district and parish councils acts in 1888 and 1894. It enabled them to overrule the wishes of the lord of the manor (which they did over common land rights) and to distribute their own kind of non-sectarian patronage.

In one sense the middle classes created class division. It was part of their attempt to establish themselves and to differentiate their new status from their past. They were so successful that many of their attitudes have been absorbed into our modern life and we imagine their attitudes were always the norm.

Family Life

At the heart of middle class philosophy was the reverence of family life. The ideal of domesticity started in the 1830s and 1840s and reached fruition in the late Victorian period. The role of the matriarch came to define our ideal of motherhood until the end of the last century. At its heart was the symbolism of wives as Madonna-like figures, who didn’t work outside the home themselves but orchestrated family life in the domestic world that they created for their households.

At the heart of middle class philosophy was the reverence of family life. The ideal of domesticity started in the 1830s and 1840s and reached fruition in the late Victorian period. The role of the matriarch came to define our ideal of motherhood until the end of the last century. At its heart was the symbolism of wives as Madonna-like figures, who didn’t work outside the home themselves but orchestrated family life in the domestic world that they created for their households.

Left: Gertrude Botcherby playing the family piano at home in 1906 (courtesy Claire Botcherby)

Left: Gertrude Botcherby playing the family piano at home in 1906 (courtesy Claire Botcherby)

The

wealth that these middle class families acquired enabled them to buy

properties with large gardens on the roads outside central Box. Their houses were properties like

the Richards family at Thornwood, Devizes Road shown in the heading photograph. These properties became their castles,

closed worlds to anyone outside their extended family sphere, where the

head of the household established new types of behaviour and etiquette.

The influence of these middle class households is still fundamental to our modern life. They introduced the idea of taking meals together, of family gatherings to listen to the piano (later the wireless, now the TV), and of taking holidays as a family unit. We are still family-centric in our domestic ideals.

The influence of these middle class households is still fundamental to our modern life. They introduced the idea of taking meals together, of family gatherings to listen to the piano (later the wireless, now the TV), and of taking holidays as a family unit. We are still family-centric in our domestic ideals.

Of course, it was an abundance of domestic space which allowed the development of family life. The middle class were able to enjoy separate areas to be with the children (the nursery, parlour, drawing room and the garden) and to be away from them (the library and the master bedroom). This was a luxury not afforded to the poor: farm labourers, many quarrymen, the elderly and especially the women who ran these households. They survived in cramped cottages with two or three rooms in which to live, cook, eat, wash and sleep.

|

To us, the houses of the poor would seem dirty, damp, dark and depressingly overcrowded. Without running water, earthen closets were a necessity and public bathing facilities in the Bingham Hall were a welcome (if occasional) taste of cleanliness.

Without birth control, there were too many children; without antibiotics, too many infant deaths. Death stalked the young. Often young babies were recorded in ink only to be crossed out later. James Manfield at Ingolls Cottages was a cowman who, during the course of completing the 1911 census, wrote beside the name of his daughter Edith slipt away. Photo right: courtesy Katherine Harris |

The

middle class had space to survive these problems; the poor resorted to

placing children with grandparents, aunts or sometimes abandoning them. The

idea that a family could live together in a property was

incomprehensible in these conditions. Instead, men resorted to the pub

and clubs to find space and women sent their children to play outside

whatever the weather.

Badly educated and extremely poor, the lowest class often had little hope of a decent family life without an improvement in their domestic living conditions. Thomas Hardy’s portrayal of rural poverty comes across powerfully and realistically. Elizabeth-Jane in The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886) endures rural life; Tess in Tess of the D'Urbervilles (1891) is ultimately destroyed by it. Whilst we now like to idealise the simplicity of rural existence, Karl Marx famously referred to the idiocy of the rural life.[3]

Houses as Castles

The great divide between the middle class and the poor was the Victorian attitude to the home. The middle class defined our meaning of domesticity, owning their own house to offer family security and privacy. Their domestic lifestyle has been defined as: a world of interior space, heavily curtained off and wary of intrusion, and opened only by invitation for viewing on occasions such as parties or teas.[4]

We see these houses throughout Box: detached and semi-detached properties built after 1870 along the Devizes Road, Bath Road and London Road. They all had their dining rooms and parlours, where guests were entertained by piano recital and readings, separated from the private areas like the kitchen and bedrooms. A sense of order was a necessity, as was the appearance of family solidarity.

The interior decoration that the middle class introduced was new and long-lasting. We still take for granted wainscoting at the bottom of the wall, friezes at the top, and wallpaper which became cheaper after 1836 when the Wallpaper Tax of 1715 was repealed. The gap between working and middle class was exacerbated by the new furnishings which graced homes at the height of imperial affluence. Houses were stuffed with rugs, wall paper, glassware, ceramics and mahogany furniture. It was an age of exhibits from all around the world and strange new gentility exemplified by antimacassars (cloth protection) on the backs of chairs to stop hair cream soiling the furniture.

Badly educated and extremely poor, the lowest class often had little hope of a decent family life without an improvement in their domestic living conditions. Thomas Hardy’s portrayal of rural poverty comes across powerfully and realistically. Elizabeth-Jane in The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886) endures rural life; Tess in Tess of the D'Urbervilles (1891) is ultimately destroyed by it. Whilst we now like to idealise the simplicity of rural existence, Karl Marx famously referred to the idiocy of the rural life.[3]

Houses as Castles

The great divide between the middle class and the poor was the Victorian attitude to the home. The middle class defined our meaning of domesticity, owning their own house to offer family security and privacy. Their domestic lifestyle has been defined as: a world of interior space, heavily curtained off and wary of intrusion, and opened only by invitation for viewing on occasions such as parties or teas.[4]

We see these houses throughout Box: detached and semi-detached properties built after 1870 along the Devizes Road, Bath Road and London Road. They all had their dining rooms and parlours, where guests were entertained by piano recital and readings, separated from the private areas like the kitchen and bedrooms. A sense of order was a necessity, as was the appearance of family solidarity.

The interior decoration that the middle class introduced was new and long-lasting. We still take for granted wainscoting at the bottom of the wall, friezes at the top, and wallpaper which became cheaper after 1836 when the Wallpaper Tax of 1715 was repealed. The gap between working and middle class was exacerbated by the new furnishings which graced homes at the height of imperial affluence. Houses were stuffed with rugs, wall paper, glassware, ceramics and mahogany furniture. It was an age of exhibits from all around the world and strange new gentility exemplified by antimacassars (cloth protection) on the backs of chairs to stop hair cream soiling the furniture.

All of this contrasted with the overcrowded and unhealthy homes of the poor. Often houses that we think of as a single residence were split into two for totally different families. It was almost impossible for agricultural labourers to establish their house as central to their family. They often lived in tied agricultural cottages, where their accommodation was dependent on their labour and might be withdrawn at retirement. In 1911 George Currant's family included his wife Ella Louise and six children aged from 8 years to 3 months squashed into three rooms at 1 Wilton Cottage, Ashley. George, aged 32, had a regular income as a railway packer for GWR but the cost of so many children meant he could not afford the rent of a larger house.

In 1911 John Moss (aged 73) was a carter who lived in totally overcrowded circumstances at Blue Vein Cottages in two rooms with his wife Dorcas (charwoman aged 47) and their three children George (16 farm labourer), Beatrice and Harriet (aged 14 and 12 school children). For the poor, a house was a night shelter and not much else. Decoration and furnishings took second place to the necessities of cooking, eating and sleeping. Maintaining the home was an enormous burden on poorer women: cleaning the grate and collecting fuel for the fire; bringing water to wash clothes and for people to bathe in; just the job of keeping the floor clean and dry when large numbers entered on wet days.

For the very poor (widows and the elderly) the work was increased by the need to take in paying guests (boarders) as a vital part of generating an income in order to fund the rent due each month. Sometimes boarders were the poorest or totally dependent. In 1911 John West was a carman (carter employed by GWR for making local deliveries) who had a boarder Ann Tiles, widow aged 82 totally blind since 46 years old.

And at the very bottom of Box's social structure in 1911 was a vagrant, Charles Franklin, who was found Wandering Found in Shed at The Meads, who called himself a general labourer.

In 1911 John Moss (aged 73) was a carter who lived in totally overcrowded circumstances at Blue Vein Cottages in two rooms with his wife Dorcas (charwoman aged 47) and their three children George (16 farm labourer), Beatrice and Harriet (aged 14 and 12 school children). For the poor, a house was a night shelter and not much else. Decoration and furnishings took second place to the necessities of cooking, eating and sleeping. Maintaining the home was an enormous burden on poorer women: cleaning the grate and collecting fuel for the fire; bringing water to wash clothes and for people to bathe in; just the job of keeping the floor clean and dry when large numbers entered on wet days.

For the very poor (widows and the elderly) the work was increased by the need to take in paying guests (boarders) as a vital part of generating an income in order to fund the rent due each month. Sometimes boarders were the poorest or totally dependent. In 1911 John West was a carman (carter employed by GWR for making local deliveries) who had a boarder Ann Tiles, widow aged 82 totally blind since 46 years old.

And at the very bottom of Box's social structure in 1911 was a vagrant, Charles Franklin, who was found Wandering Found in Shed at The Meads, who called himself a general labourer.

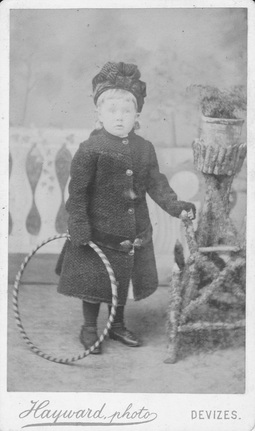

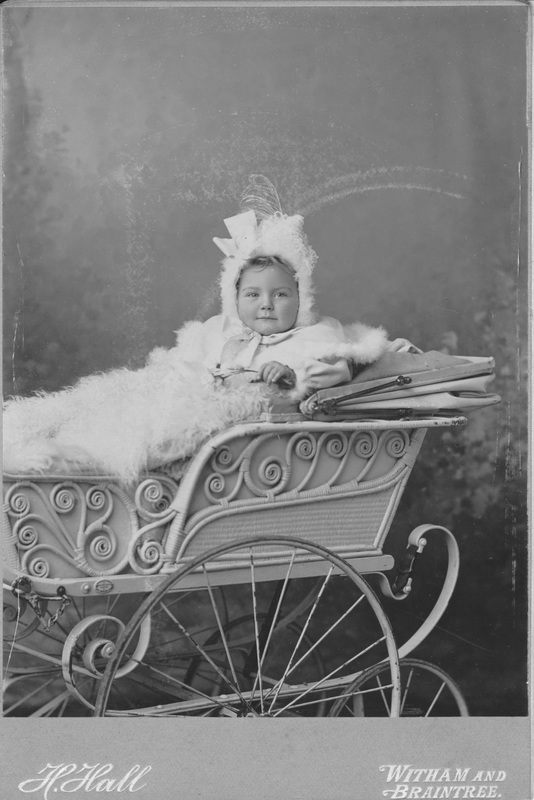

Children

Perhaps the driving purpose of the middle classes was to establish family dynasties for themselves and their offspring. It has been said that the late Victorians created childhood as a precious time to be awarded to children, allowing them to play and enjoy a period of growing up before embarking on a life of adult work. There are many photos of children in this series which would have been unthought-of in previous times.

Perhaps the driving purpose of the middle classes was to establish family dynasties for themselves and their offspring. It has been said that the late Victorians created childhood as a precious time to be awarded to children, allowing them to play and enjoy a period of growing up before embarking on a life of adult work. There are many photos of children in this series which would have been unthought-of in previous times.

All photos in this section come from Phil Lambert's marvellous family album of residents in Box (courtesy Margaret Wakefield).

The individualism of these middle class children, posed and preparing to take their role in society, contrasts greatly with the over-crowded group photos of their working class contemporaries. For them photos were often a once-only occasion, facilitated at school and depressingly uniform in their attitude to individuals.

The educational level of working class children on leaving school severely restricted their later employment opportunities. It was only in 1870 that the idea of compulsary schooling was adopted by the government and this was not introduced in practice until the 1880 Act made attendance compulsory for children aged 5 to 10 years.[5] Subsequent Acts raised the leaving age and by 1899 the minimum leaving age was set at 12 years. Little wonder that so many adults failed to have the basic reading and writing skills needed for anything other than labouring work!

Things were no better when working class children left school. Many poor lads became errand boys or assisted as agricultural labourers or in the quarry trade. For girls, adolescence often meant a decade spent away from home in service. All along the London Road were the semi-detached villas of Box's lower middle class residents and in the attic lived the maid of all work (general servant). In 1901 a fifth of employed women in Britain were in domestic service, which was by the far the largest single occupational group. Usually the live-in servants were not local to their employment area to reduce the risk that they would abscond and return home.

There were maids in service in most of the affluent Box households in 1911. At Hatt House was Edmund Story-Maskelyne, a retired barrister aged 81, who lived with his wife, Martha, in 14 rooms looked after by a cook (Mary Painter aged 28), parlour maid (Florence Thorne, 24), and housemaid (Ethel Painter, 22). Beatrice Northey (widow of 48 years) lived in ten rooms at Holmelea with her daughter, a companion and two servants, a domestic cook and house parlour maid.

Things were no better when working class children left school. Many poor lads became errand boys or assisted as agricultural labourers or in the quarry trade. For girls, adolescence often meant a decade spent away from home in service. All along the London Road were the semi-detached villas of Box's lower middle class residents and in the attic lived the maid of all work (general servant). In 1901 a fifth of employed women in Britain were in domestic service, which was by the far the largest single occupational group. Usually the live-in servants were not local to their employment area to reduce the risk that they would abscond and return home.

There were maids in service in most of the affluent Box households in 1911. At Hatt House was Edmund Story-Maskelyne, a retired barrister aged 81, who lived with his wife, Martha, in 14 rooms looked after by a cook (Mary Painter aged 28), parlour maid (Florence Thorne, 24), and housemaid (Ethel Painter, 22). Beatrice Northey (widow of 48 years) lived in ten rooms at Holmelea with her daughter, a companion and two servants, a domestic cook and house parlour maid.

|

Some historians have tried to justify the system by referring to the education poor girls were given when they became part of a middle-class household. The girls were clothed in smart uniforms and educated by their mistress in the middle-class values of obedience, sobriety and, above all, service to God through hard work.

But the volume and harshness of the work cannot be excused. They did the cooking, dish washing, fire lighting, child care and all domestic drudgery. Often they were on duty from 7am to 10pm with a half day off on Sunday to go to church.[6] Right Marjorie Hancock in service (courtesy Bob Hancock) |

Many

servants came from the extremes of poverty or the workhouse, where they

were taught sewing, laundry and cleaning to prepare them for service.

In the 1870s to 1890s charities like Barnardos and the Girls Friendly Societies placed orphans as young as 11 and 12 years as servants to stop them being tainted as work-shy adults. These girls often became tweenies (the lowest of all servants) who collected the chamber pot and bed pans, fetched water and carried coal to the fire grates.

One of the main drivers for female domestic service was rural underemployment in Southern England where there were insufficient jobs to support the growing population. Service became a particularly female occupation because a tax on male servants had existed since the 1770s, restricting them to the butlers and coachmen of the very weathy. Without the opportunity of service, a lot of young men emigrated to the New Worlds of Canada, Australia and USA.

In the 1870s to 1890s charities like Barnardos and the Girls Friendly Societies placed orphans as young as 11 and 12 years as servants to stop them being tainted as work-shy adults. These girls often became tweenies (the lowest of all servants) who collected the chamber pot and bed pans, fetched water and carried coal to the fire grates.

One of the main drivers for female domestic service was rural underemployment in Southern England where there were insufficient jobs to support the growing population. Service became a particularly female occupation because a tax on male servants had existed since the 1770s, restricting them to the butlers and coachmen of the very weathy. Without the opportunity of service, a lot of young men emigrated to the New Worlds of Canada, Australia and USA.

|

Good Manners

Contemporaries had no difficulty defining the class to which they belonged - it was quite evident by the manners people showed. Not least of these was the Victorian attitude to death and mourning. The widow of a middle class man was expected to wear full black silk and crepe clothing (First Mourning) for a year and one month; followed by Second Mourning with less crepe for a further six months; then Ordinary Mourning for six months with no crepe; and finally Half Mourning where lavender and grey were allowed as colours.[7] Of course you earned greater respect by extending these time periods in imitation of Queen Victoria herself. The initial success of Courtaulds was based on supplying enormous quantities of mourning crepe to middle aged, middle class women and the company only later turned to synthetics. It goes without saying that the battle to avoid destitution was more important to many working class women than respect through sartorial elegance. Left: Sarah Jane Kingston, the mother of TH Lambert, seen in mourning clothes (photo courtesy Margaret Wakefield) |

Religious Divide

Class divisions were apparent in every aspect of late Victorian life, including religious beliefs. By belief as well as convenience the middle class families in central Box attended the established church at St Thomas à Becket. But this was not the same for the working class families living at of Kingsdown and Quarry Hill. Instead the out-reach work of Methodist preachers took religion to them, building a number of Mission Chapels in the hamlets at Quarry Hill, Kingsdown, Beech Road and Prospect.

Class divisions were apparent in every aspect of late Victorian life, including religious beliefs. By belief as well as convenience the middle class families in central Box attended the established church at St Thomas à Becket. But this was not the same for the working class families living at of Kingsdown and Quarry Hill. Instead the out-reach work of Methodist preachers took religion to them, building a number of Mission Chapels in the hamlets at Quarry Hill, Kingsdown, Beech Road and Prospect.

It was the Methodist Church movement that did much to offer hope of improvement to the working class and in so doing the poor embraced the concept of dignity for their own class. (The word posh still has overtones of pretentiousness above one's station.) The sharing of testimony built up confidence in the poor as God's chosen children; dissenting schools encouraged education; and absenteeism (teetotalism) encouraged moral and socially acceptable behaviour.

Leisure and Outings

Part of the proof of being middle class was the demonstration of time for leisure and etiquette (gentility) by the family adults. Family picnics to Kingsdown were a good way to show breeding and wealth whatever the ground conditions. It was a stroll or gentle ride from the village and more rural than the old Fete Field, at the foot of the Box Tunnel.

Part of the proof of being middle class was the demonstration of time for leisure and etiquette (gentility) by the family adults. Family picnics to Kingsdown were a good way to show breeding and wealth whatever the ground conditions. It was a stroll or gentle ride from the village and more rural than the old Fete Field, at the foot of the Box Tunnel.

The poor had little time for such outings but when they did it was usually at Fete Field (now Bargates) where children of the village might more easily gather to play. The effects of the Great War reduced the inclination for leisure and also encouraged greater mixing by children.

Mixing of Classes

This photo below shows children of the village celebrating at Fete Field under the old Oak Tree in 1916.

It shows a mixing of classes, albeit coloured by the innocence of childhood, which we expect for all adults in Box today.

The children shown include: Anthea Eyles, Dick Eyles, Frank Bradbury, Mac Davies, Donald Bradfield, Joan Pearson, Judy Davies, Jean Davies, Phil Lambert and Douglas Creighton.

If you can identify any of the others, we would love to hear from you via the Contact page.

The children shown here attended Box school but not all children in the area did so in 1911. John Betteridge was a delver (ditch digger at stone quarry) at Kingsdown who sent his son aged 10 to school but could not afford to send his daughter Gwendolyn aged 9, who worked at home.

(photo courtesy Margaret Wakefield)

This photo below shows children of the village celebrating at Fete Field under the old Oak Tree in 1916.

It shows a mixing of classes, albeit coloured by the innocence of childhood, which we expect for all adults in Box today.

The children shown include: Anthea Eyles, Dick Eyles, Frank Bradbury, Mac Davies, Donald Bradfield, Joan Pearson, Judy Davies, Jean Davies, Phil Lambert and Douglas Creighton.

If you can identify any of the others, we would love to hear from you via the Contact page.

The children shown here attended Box school but not all children in the area did so in 1911. John Betteridge was a delver (ditch digger at stone quarry) at Kingsdown who sent his son aged 10 to school but could not afford to send his daughter Gwendolyn aged 9, who worked at home.

(photo courtesy Margaret Wakefield)

After World War 1

After 1918 many of the pretensions of class division appeared ridiculous. War took lives regardless of social position, morals or religious beliefs. Conscription in the Great War brought together people of different classes and showed that their spirit was more important than family status.

After 1918 many of the pretensions of class division appeared ridiculous. War took lives regardless of social position, morals or religious beliefs. Conscription in the Great War brought together people of different classes and showed that their spirit was more important than family status.

Elsie and Doris Wilkins posing in the latest fashion (photo courtesy Stella Clarke).[8]

Elsie and Doris Wilkins posing in the latest fashion (photo courtesy Stella Clarke).[8]

There were enormous structural changes in the economy after 1918, including the growth of white-collar jobs; more working opportunities for women; a massive decline in domestic service; and the growth of the new industries in the south of the country (especially around Bristol) which led to a flight from the countryside into the towns.

Economic decline and the depression of the 1920s also reduced the divisions in society. Agriculture continued to have long-term problems in rural areas mainly caused by lack of investment. And many of Box's manufacturing industries, like Box Brewery and Box Mill, declined until their ultimate closure or change of use.

Social change was encouraged by technological innovation such as the rise of the cinema. The Roaring Twenties and the Flapper style of clothing of that time affected all classes in society, keen to move forward from the difficulties of the previous decade. Some people could afford to buy the latest styles; others produced their own versions of sartorial elegance.

The growth in newspapers (and women's magazines in particular) and better education meant an increase in aspiration (and income) to emulate the mores and fashions of superior stratas of society.

Economic decline and the depression of the 1920s also reduced the divisions in society. Agriculture continued to have long-term problems in rural areas mainly caused by lack of investment. And many of Box's manufacturing industries, like Box Brewery and Box Mill, declined until their ultimate closure or change of use.

Social change was encouraged by technological innovation such as the rise of the cinema. The Roaring Twenties and the Flapper style of clothing of that time affected all classes in society, keen to move forward from the difficulties of the previous decade. Some people could afford to buy the latest styles; others produced their own versions of sartorial elegance.

The growth in newspapers (and women's magazines in particular) and better education meant an increase in aspiration (and income) to emulate the mores and fashions of superior stratas of society.

Lasting Impact

We have referred to the development of the middle classes in general but are there any specific results that have remained with us in Box? We have seen that there were few conflicts between the middle and working classes in the village. Partly this was because middle class families often evolved out of quarry workers, so they understood better the working conditions of the employees in their charge. At the same time, the working classes were themselves aspirational as proto-employers through the ganger system in the stone works.

As a result, there was considerable harmony in employer-employee relations in Victorian Box. Perhaps we still see the outcome of these social changes in the community spirit that Box is reputed to enjoy today. This unity makes the current discussion about changing the parish boundaries to move Rudloe out of Box into Corsham all the more inexplicable. Let the councils be wary of disrupting the parish's historic harmony for short-term expediency.

We have referred to the development of the middle classes in general but are there any specific results that have remained with us in Box? We have seen that there were few conflicts between the middle and working classes in the village. Partly this was because middle class families often evolved out of quarry workers, so they understood better the working conditions of the employees in their charge. At the same time, the working classes were themselves aspirational as proto-employers through the ganger system in the stone works.

As a result, there was considerable harmony in employer-employee relations in Victorian Box. Perhaps we still see the outcome of these social changes in the community spirit that Box is reputed to enjoy today. This unity makes the current discussion about changing the parish boundaries to move Rudloe out of Box into Corsham all the more inexplicable. Let the councils be wary of disrupting the parish's historic harmony for short-term expediency.

References

[1] EP Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, 1963, Victor Gollancz Ltd

[2] Roger J Tucker, Some Notable Wiltshire Quarrymen, free Troglophite Association Press

[3] Karl Marx, Communist Manifesto, 1848, Chapter 1

[4] http://www.historygraphicdesign.com/index.php/industrial-revolution/the-industrial-revolution/637-victorian-era

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raising_of_school_leaving_age_in_England_and_Wales

[6] Pamela Cox, Servants: The True Story of Life Below Stairs, 2012, BBC TV

[7] Manners and Rules of Good Society, or, Solecisms to be Avoided, 1887, Frederick Warne & Co

[8] You can read Stella's amazing life story at A Lifetime of Memories.

[1] EP Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, 1963, Victor Gollancz Ltd

[2] Roger J Tucker, Some Notable Wiltshire Quarrymen, free Troglophite Association Press

[3] Karl Marx, Communist Manifesto, 1848, Chapter 1

[4] http://www.historygraphicdesign.com/index.php/industrial-revolution/the-industrial-revolution/637-victorian-era

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raising_of_school_leaving_age_in_England_and_Wales

[6] Pamela Cox, Servants: The True Story of Life Below Stairs, 2012, BBC TV

[7] Manners and Rules of Good Society, or, Solecisms to be Avoided, 1887, Frederick Warne & Co

[8] You can read Stella's amazing life story at A Lifetime of Memories.