Village Celebrations Alan Payne November 2014

It

is hard for us to believe that half of Box's population could sit down

and enjoy a communal afternoon tea together.

But that happened several times between 1890 and 1910. Nowadays when something significant happens we all turn on our televisions to access the latest information. That is what happened when man landed on the moon, for the death of Princess Diana and for the London Olympics.

In Victorian times, before such media, people got their information from sermons in the church pulpit, from notices in newspapers and from local gossip. But these ways did not allow everyone to access accurate information at the same time. The great communal public gatherings in the village reinforced the news in a way that is unimaginable in our time. This is the story of those gatherings from photographs taken at the time.

But that happened several times between 1890 and 1910. Nowadays when something significant happens we all turn on our televisions to access the latest information. That is what happened when man landed on the moon, for the death of Princess Diana and for the London Olympics.

In Victorian times, before such media, people got their information from sermons in the church pulpit, from notices in newspapers and from local gossip. But these ways did not allow everyone to access accurate information at the same time. The great communal public gatherings in the village reinforced the news in a way that is unimaginable in our time. This is the story of those gatherings from photographs taken at the time.

Background

The 1890s has been seen as a decade of Naughtiness with a newly-discovered freedom from Victorian social restraint.

It was a time of domestic peace and greater affluence and, for some in Box, the excitement of new, decadent art and literature; and the opportunity to travel with time for leisure to socialise with friends and family.

Whilst much of this perception has been created by the nostalgic reminiscences of people after the Great War, there were several times in Box when partying and pleasure was enjoyed by the whole village. This article seeks to record some of the communal fun and festivities of ordinary Box residents at this time. Many of the communal festivities in Box related to national events, royal jubilees and coronations.

Victorian Jubilees

Communal celebrations were an opportunity for the whole village to join together as a community, often full of nostalgia and patriotic sentimentality. For Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887 the Box Jubilee Festival Committee organised a procession and church service. There were bonfires on hills all around and the celebration was followed by a magnificent dinner for 1,100 parishioners, tea for 800 children and the presentation of special commemorative mugs, a few of which are still intact.

The 1890s has been seen as a decade of Naughtiness with a newly-discovered freedom from Victorian social restraint.

It was a time of domestic peace and greater affluence and, for some in Box, the excitement of new, decadent art and literature; and the opportunity to travel with time for leisure to socialise with friends and family.

Whilst much of this perception has been created by the nostalgic reminiscences of people after the Great War, there were several times in Box when partying and pleasure was enjoyed by the whole village. This article seeks to record some of the communal fun and festivities of ordinary Box residents at this time. Many of the communal festivities in Box related to national events, royal jubilees and coronations.

Victorian Jubilees

Communal celebrations were an opportunity for the whole village to join together as a community, often full of nostalgia and patriotic sentimentality. For Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887 the Box Jubilee Festival Committee organised a procession and church service. There were bonfires on hills all around and the celebration was followed by a magnificent dinner for 1,100 parishioners, tea for 800 children and the presentation of special commemorative mugs, a few of which are still intact.

|

These celebrations were outdone in 1896 by the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee.[1] The first task of the newly-formed Parish Council was to organise the festivities to celebrate the Queen’s achievements. The organising committee decided that a Festival was to be held following the lines of the earlier celebration and in addition a Permanent Memorial, in the shape of a Clock, to be placed in the School Tower.[2]

Proceedings followed the earlier arrangements: On Jubilee Day at 10.30, the Members of the Loyal Northey Lodge of Oddfellows, the Foresters (Bold Robin Hood) and members of other Societies met at the Schools, and formed a procession, headed by the Lyneham Brass Band... The village, which presented a festive appearance, was then paraded. |

(At) a field adjoining the Fete Field, kindly lent by Mr J Vezey (Chequers), over 1,100 sat down to a good dinner... After dinner came what has been described as one of the prettiest sights of the day. The members of the Ladies’ Committee, assisted by several gentlemen of the General Committee, marshalled the children at the Schools and, headed by the Band, proceeded to the field where a bountiful Tea was awaiting them. About 700 Children and 200 Adults partook thereof.[3]

Edwardian Period

For older Victorians, Queen Victoria stood for stability, certainty and the power of the British Empire. But by the end of her reign, many people had tired of the drabness of Victorian fashions and morality and wanted a fresh start. This can be seen in the celebrations of the new Edwardian era.

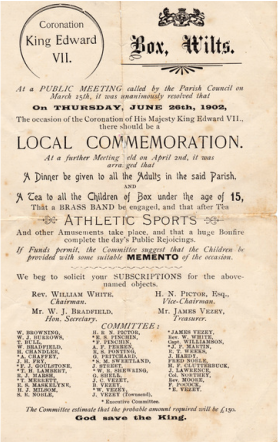

On 9 August 1902 there was the coronation of King Edward VII. A great many people had decorated their houses, which were prettily and effectively lighted at night and the streets were gay with flags and banners. An immense array of tables had been prepared in the fete grounds, covers being laid for 1,200 people.[5]

The Parish Council agreed to a dinner for all adults in the Parish and a tea for all children under 15 years with a Brass Band after the tea, Athletic Sports and other amusements including a huge bonfire.[6] Finally, there was a suitable memento (unspecified) of the occasion for the children.

Right: Notice by Box Parish Council in 1902 (courtesy Ainslie Goulstone)

Coronation of George V in June 1911

For older Victorians, Queen Victoria stood for stability, certainty and the power of the British Empire. But by the end of her reign, many people had tired of the drabness of Victorian fashions and morality and wanted a fresh start. This can be seen in the celebrations of the new Edwardian era.

On 9 August 1902 there was the coronation of King Edward VII. A great many people had decorated their houses, which were prettily and effectively lighted at night and the streets were gay with flags and banners. An immense array of tables had been prepared in the fete grounds, covers being laid for 1,200 people.[5]

The Parish Council agreed to a dinner for all adults in the Parish and a tea for all children under 15 years with a Brass Band after the tea, Athletic Sports and other amusements including a huge bonfire.[6] Finally, there was a suitable memento (unspecified) of the occasion for the children.

Right: Notice by Box Parish Council in 1902 (courtesy Ainslie Goulstone)

Coronation of George V in June 1911

Later Celebrations

By the mid-1900s the great celebratory gatherings were over, overshadowed by media presentations and cultural change. The Silver Jubilee of King George V in 1935 was hampered by the fear of war arising in Europe. We might imagine that the number of men on the committee organising the commemorations (pictured below) reflects these social strains. In May 1935 there was an open-air church service at The Northey Arms Hotel attended by 500 people. The celebrations moved to the Recreation Ground where there was folk dancing, and the King’s Speech, The Empire Broadcast, went out on the wireless.

In the evening there was a Chinese lantern procession and fireworks and Jubilee mugs were presented.[7] There were personal contributions to the festivities from the singer, Evelyn Laye, who entertained at The Northey Arms, which was owned by the actress, Miss Maisey Gay, who lived in The Whirligig (the name of her film) near The Swan.[8]

By the mid-1900s the great celebratory gatherings were over, overshadowed by media presentations and cultural change. The Silver Jubilee of King George V in 1935 was hampered by the fear of war arising in Europe. We might imagine that the number of men on the committee organising the commemorations (pictured below) reflects these social strains. In May 1935 there was an open-air church service at The Northey Arms Hotel attended by 500 people. The celebrations moved to the Recreation Ground where there was folk dancing, and the King’s Speech, The Empire Broadcast, went out on the wireless.

In the evening there was a Chinese lantern procession and fireworks and Jubilee mugs were presented.[7] There were personal contributions to the festivities from the singer, Evelyn Laye, who entertained at The Northey Arms, which was owned by the actress, Miss Maisey Gay, who lived in The Whirligig (the name of her film) near The Swan.[8]

The 1935 Commemoration Committee: Back row: P Lambert, R Blake, C Filder, J Abrahams, ?, F Nowell, H Rothery-Basinger, C Cox, H Armstead, Mr Vaughan, A Weekes. Middle Row: Rev G Foster, Hon Mrs Shaw-Mellor, J Browning, CW Oatley. Front row: F Merrett, W Dermott, A Cogswell, N Martin. (Photo courtesy Margaret Wakefield)

Conclusion

The Victorian and Edwardian times depicted in these photos are very different from our own age when news is accessed through social media on the internet by individuals on their own. There are aspects of these meetings that are gone forever: the belief that Sundays were different to working weekdays and had to be enjoyed in a proper way; the middle-class desire to educate children within one's responsibility; and the desire to glorify national public figures and British imperialism.

Of course it was the wealth of the village as well as the sense of occasion that allowed such communal events. But there is more to it than that. There are aspects that we still treasure including the recording of a simple pride in being acknowledged as part of the community of the village of Box.

The Victorian and Edwardian times depicted in these photos are very different from our own age when news is accessed through social media on the internet by individuals on their own. There are aspects of these meetings that are gone forever: the belief that Sundays were different to working weekdays and had to be enjoyed in a proper way; the middle-class desire to educate children within one's responsibility; and the desire to glorify national public figures and British imperialism.

Of course it was the wealth of the village as well as the sense of occasion that allowed such communal events. But there is more to it than that. There are aspects that we still treasure including the recording of a simple pride in being acknowledged as part of the community of the village of Box.

References

[1] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire: An Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.49

[2] Reprinted in Parish Magazine, June 1930

[3] Parish Magazine, June 1930

[4] Photo and details courtesy of Jane Browning

[5] Parish Magazine, September 1902

[6] Programme and photos courtesy of Ainslie Goulstone

[7] Parish Magazine, May 1935

[8] Victor Painter, Kingsdown Memories, WRO

[1] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire: An Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.49

[2] Reprinted in Parish Magazine, June 1930

[3] Parish Magazine, June 1930

[4] Photo and details courtesy of Jane Browning

[5] Parish Magazine, September 1902

[6] Programme and photos courtesy of Ainslie Goulstone

[7] Parish Magazine, May 1935

[8] Victor Painter, Kingsdown Memories, WRO