Buried in Box Cemetery Alan Payne June 2024

Cemeteries are very curious places. They are obviously full of dead people and the sadness of our loss. But they are also abundant with natural life, flowers, birds and grasses and a visit there gives us a closer connection with the past. Seeing the headstones of these graves gives us vivid memories of our heritage, the people and events in Box village. Box Cemetery helps to enrich our lives. This article records some of the hidden stories in our cemetery.

Building the Cemetery After Alleged Murders, 1858

Box cemetery, the cemetery lodge and the chapel were all built in 1858, after the mysterious deaths of the wife and sister-in-law of the Rev Holled Daryl Cave Smith Horlock, vicar of Box. The deaths occurred after a family meal at Box House but nobody else was affected. Box villagers suspected foul deeds but the church diocesan council believed the cause came from fumes emitted in the churchyard of St Thomas à Becket, which was immediately closed for new burials.[1] Hence the need for the Box Cemetery, the earliest public village cemetery in England.

Land for the site was donated by the Northey family, lords of Box manor, a short distance from the village adjoining the turnpike road (the A4 road built to access the railway station). It was created for the benefit of all villagers and part of the 2-acre site was set apart for the use of Dissenters. Considerable effort was made in the organisation of the area. The graves were laid out to face Jerusalem in the east and affording a view of Box Valley to the north for all graves. Considerable effort was made to soften the appearance of the site with charming Box stone buildings of rubble, ashlar and carved stone laid to decorative effect.[2]

Box cemetery, the cemetery lodge and the chapel were all built in 1858, after the mysterious deaths of the wife and sister-in-law of the Rev Holled Daryl Cave Smith Horlock, vicar of Box. The deaths occurred after a family meal at Box House but nobody else was affected. Box villagers suspected foul deeds but the church diocesan council believed the cause came from fumes emitted in the churchyard of St Thomas à Becket, which was immediately closed for new burials.[1] Hence the need for the Box Cemetery, the earliest public village cemetery in England.

Land for the site was donated by the Northey family, lords of Box manor, a short distance from the village adjoining the turnpike road (the A4 road built to access the railway station). It was created for the benefit of all villagers and part of the 2-acre site was set apart for the use of Dissenters. Considerable effort was made in the organisation of the area. The graves were laid out to face Jerusalem in the east and affording a view of Box Valley to the north for all graves. Considerable effort was made to soften the appearance of the site with charming Box stone buildings of rubble, ashlar and carved stone laid to decorative effect.[2]

Village Funeral Processions

Before the A4 became so busy it was usual to process from the home of the deceased to Box Church and then to the cemetery. The funeral procession of quarryman Henry Eyles comprised family, friends, work colleagues and ninety members of the Loyal Northey Lodge of Oddfellows and representatives of the Ancient Order of Foresters (Box's Bold Robin Hood Court), all of whom proceeded in their funeral regalia from Quarry Hill to the cemetery.[3]

There was a similar formal procession in 1903 for the funeral of Mr E Gane of Kingsdown, aged 30 years, which comprised thirty members of the Shepherds-on-the-Avon Lodge of the Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds, who processed carrying their crooks.[4] They were joined by quarrymen from the area and members of the Kingsdown Working Men's Club.

Sometimes many hundreds of villagers gathered at the cemetery to commemorate the deaths of well-known local people.

When Walter Richard Shewring of The Paddock, Box, died in 1911 nearly all the inhabitants of Box attended.[5] Mr Shewring's death shocked villagers because he had been part of so many Box organisations, licensee of The Northey Arms, foreman of the Box Station Stoneyards, Overseer of the Poor for Box Parish Council, active player for the Box Cricket Club and many others.

His funeral bier was carried by employees of the Stone Wharf and flanked by the Box detachment of Boy Scouts, which Walter

had helped to found a year earlier.

Before the A4 became so busy it was usual to process from the home of the deceased to Box Church and then to the cemetery. The funeral procession of quarryman Henry Eyles comprised family, friends, work colleagues and ninety members of the Loyal Northey Lodge of Oddfellows and representatives of the Ancient Order of Foresters (Box's Bold Robin Hood Court), all of whom proceeded in their funeral regalia from Quarry Hill to the cemetery.[3]

There was a similar formal procession in 1903 for the funeral of Mr E Gane of Kingsdown, aged 30 years, which comprised thirty members of the Shepherds-on-the-Avon Lodge of the Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds, who processed carrying their crooks.[4] They were joined by quarrymen from the area and members of the Kingsdown Working Men's Club.

Sometimes many hundreds of villagers gathered at the cemetery to commemorate the deaths of well-known local people.

When Walter Richard Shewring of The Paddock, Box, died in 1911 nearly all the inhabitants of Box attended.[5] Mr Shewring's death shocked villagers because he had been part of so many Box organisations, licensee of The Northey Arms, foreman of the Box Station Stoneyards, Overseer of the Poor for Box Parish Council, active player for the Box Cricket Club and many others.

His funeral bier was carried by employees of the Stone Wharf and flanked by the Box detachment of Boy Scouts, which Walter

had helped to found a year earlier.

Significant Headstones

The use of upright headstones to mark burials is comparatively modern and originally headstones were the slab over the grave. Traditional Christian headstones have the name of deceased, date of birth and death, and often a family obituary or inscription. Sometimes there is a hidden message in the headstone, a pillow for rest, an angel for grief, a dove for the Holy Spirit.

The use of upright headstones to mark burials is comparatively modern and originally headstones were the slab over the grave. Traditional Christian headstones have the name of deceased, date of birth and death, and often a family obituary or inscription. Sometimes there is a hidden message in the headstone, a pillow for rest, an angel for grief, a dove for the Holy Spirit.

World War I Epitaphs

The decision about who should be honoured as a war casualty was not straightforward. Of course, the death of loved-ones became more intensely disturbing during times of war. Servicemen could be recorded in the parish of their origin, even though some might have been absent before the war. This presented issues where the parents had made their home in Box but the serviceman had a family living elsewhere. Both families wanted their loss to be recorded locally where they could be hooured with flowers and tending of the grave. In the end the decision was left to villagers who added names to the list displayed on Box High Street.

There was the problem of the place of death. Some men died in the mud killed going over the top. The bodies of many of these men were never recovered and their possible remains were reinterred in the Commonwealth Graves in Flanders France and Gallipoli CHECK, where the names were recorded on mass placques that they should not be forgotten. The agreement in Box was that their names were included on the War Memorial but they should have no gravestone in the cemetery. Other men lost their lives in England, some handling explosives,;others killed in training accidents; some killed in the fighting in Ireland, usually described as killed on the Home Front.

Finally, there was the name of the death. Some men were returned to Box for recuperation who died later of wounds sustained or the after-effects of gas inhalation. There obviously had to be a cut-off date MORE.

Lewis William Smith

Few are as tragic as the death of Lewis William Smith, of Hill Lane, Box, in the First World War.[6] He had served in the Royal Navy for six years before his ship was sunk leaving him floating in the sea for 9½ hours before rescue. Returning to duty he was posted as leading torpedo operator on a submarine before his dreadful former experience undermined his splendid constitution and he died at home, aged 24. His coffin was pulled to the graveside by members of the 3rd Wilts Voluntary Aid Detachment of nurses substituting for Devonport Naval Command who were unable to supply an escort and firing party for a full naval funeral, although the Last Post was sounded.

The seven servicemen from the First World War buried in the cemetery are marked by a variety of headstones. Four are the standard Commonwealth War Graves Commission design with a standard cross, others are in family plots and remembered as part of membership of their relatives. Most show the badge of their regiment, the deceased's name, rank, name, unit, date of death and age. The personal dedication chosen by relatives reads:

Arthur John Cox xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Herbert Percy Hancock Peace Perfect Peace

Reginald Isaac Hancock Also xxxxxxxxxxxxx

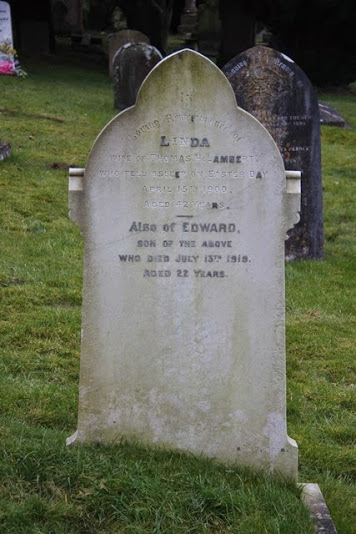

Edward Lambert family grave

George William Milsom no inscription

Lewis William Smith Peace Perfect Peace

Percival Vezey family grave.

If you visit Box Cemetery, please spare them a thought.

The decision about who should be honoured as a war casualty was not straightforward. Of course, the death of loved-ones became more intensely disturbing during times of war. Servicemen could be recorded in the parish of their origin, even though some might have been absent before the war. This presented issues where the parents had made their home in Box but the serviceman had a family living elsewhere. Both families wanted their loss to be recorded locally where they could be hooured with flowers and tending of the grave. In the end the decision was left to villagers who added names to the list displayed on Box High Street.

There was the problem of the place of death. Some men died in the mud killed going over the top. The bodies of many of these men were never recovered and their possible remains were reinterred in the Commonwealth Graves in Flanders France and Gallipoli CHECK, where the names were recorded on mass placques that they should not be forgotten. The agreement in Box was that their names were included on the War Memorial but they should have no gravestone in the cemetery. Other men lost their lives in England, some handling explosives,;others killed in training accidents; some killed in the fighting in Ireland, usually described as killed on the Home Front.

Finally, there was the name of the death. Some men were returned to Box for recuperation who died later of wounds sustained or the after-effects of gas inhalation. There obviously had to be a cut-off date MORE.

Lewis William Smith

Few are as tragic as the death of Lewis William Smith, of Hill Lane, Box, in the First World War.[6] He had served in the Royal Navy for six years before his ship was sunk leaving him floating in the sea for 9½ hours before rescue. Returning to duty he was posted as leading torpedo operator on a submarine before his dreadful former experience undermined his splendid constitution and he died at home, aged 24. His coffin was pulled to the graveside by members of the 3rd Wilts Voluntary Aid Detachment of nurses substituting for Devonport Naval Command who were unable to supply an escort and firing party for a full naval funeral, although the Last Post was sounded.

The seven servicemen from the First World War buried in the cemetery are marked by a variety of headstones. Four are the standard Commonwealth War Graves Commission design with a standard cross, others are in family plots and remembered as part of membership of their relatives. Most show the badge of their regiment, the deceased's name, rank, name, unit, date of death and age. The personal dedication chosen by relatives reads:

Arthur John Cox xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Herbert Percy Hancock Peace Perfect Peace

Reginald Isaac Hancock Also xxxxxxxxxxxxx

Edward Lambert family grave

George William Milsom no inscription

Lewis William Smith Peace Perfect Peace

Percival Vezey family grave.

If you visit Box Cemetery, please spare them a thought.

Left to Right, Above: Arthur Cox, Herbert Hancock, Reginald Hancock and Edward Lambert

Below: George Milsom, Lewis Smith and Percival Vezey (courtesy Open Parish Clerk)

Below: George Milsom, Lewis Smith and Percival Vezey (courtesy Open Parish Clerk)

Box Cemetery has always been comitted to honouring the dead regardless of the circumstances. There are several examples of the burial of the unfortunate people who may have committed suicide. Lieut-Col William Eustace St John, DSO, committed suicide at Lansdown, Bath, by shooting himself with a pistol.[7] He had previously served in both the Boer War and Great War.

Box Cemetery agreed to take the body and six members of the local constabulary, including Box's PC Gape and Special Constable Gingell, acted as pall-bearers.

One of the most unusual of burials was during the Second World War when four or five German airmen were buried with dignity and honour in a corner of the cemetery. Arthur Maltin, vicar of Box, wrote movingly in 1940, They were buried decently and with military honours because, if there is one shred of international honour left, it is to treat with respect the enemy dead.[8] They were given wooden crosses and stayed here until the German government repatriated to a German cemetery in 1963.

Box Cemetery agreed to take the body and six members of the local constabulary, including Box's PC Gape and Special Constable Gingell, acted as pall-bearers.

One of the most unusual of burials was during the Second World War when four or five German airmen were buried with dignity and honour in a corner of the cemetery. Arthur Maltin, vicar of Box, wrote movingly in 1940, They were buried decently and with military honours because, if there is one shred of international honour left, it is to treat with respect the enemy dead.[8] They were given wooden crosses and stayed here until the German government repatriated to a German cemetery in 1963.

Place of Peace and Consolation

Obviously, the burial of children is some of the saddest of all the graves in the cemetery. There are many in Box, including the death of two infants in the Manor House in 1963, who were suffocated by smoke inhalation caused by a paraffin stove.

Their simple headstones are a tribute to dignity amidst great suffering.

For some, there is only the tragedy of a sad and lonely passing. One of Box's famous residents was the Hon Mrs Twisleton of Heleigh House, Middlehill. She had many noble ancestors, the granddaughter of Lord Audley, daughter-in-law of Lord Saye and Sele, and wife of the Hon Charles Twisleton. Her death was recorded in 1933 as She led a secluded life. There is no family.[9]

By remembering her and others when we visit Box Cemetery, we try to give them peace.

Obviously, the burial of children is some of the saddest of all the graves in the cemetery. There are many in Box, including the death of two infants in the Manor House in 1963, who were suffocated by smoke inhalation caused by a paraffin stove.

Their simple headstones are a tribute to dignity amidst great suffering.

For some, there is only the tragedy of a sad and lonely passing. One of Box's famous residents was the Hon Mrs Twisleton of Heleigh House, Middlehill. She had many noble ancestors, the granddaughter of Lord Audley, daughter-in-law of Lord Saye and Sele, and wife of the Hon Charles Twisleton. Her death was recorded in 1933 as She led a secluded life. There is no family.[9]

By remembering her and others when we visit Box Cemetery, we try to give them peace.

References

[1] The Bath Chronicle, 16 December 1858

[2] Julian Orbach, author of the revised edition of 'The Buildings of England. Wiltshire by Nikolaus Pevsner”

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 17 July 1890

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 19 November 1903

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 23 February 1911

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 1 December 1917

[7] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 23 May 1931

[8] Parish Magazine, October 1940

[9] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 25 November 1933

[1] The Bath Chronicle, 16 December 1858

[2] Julian Orbach, author of the revised edition of 'The Buildings of England. Wiltshire by Nikolaus Pevsner”

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 17 July 1890

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 19 November 1903

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 23 February 1911

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 1 December 1917

[7] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 23 May 1931

[8] Parish Magazine, October 1940

[9] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 25 November 1933