|

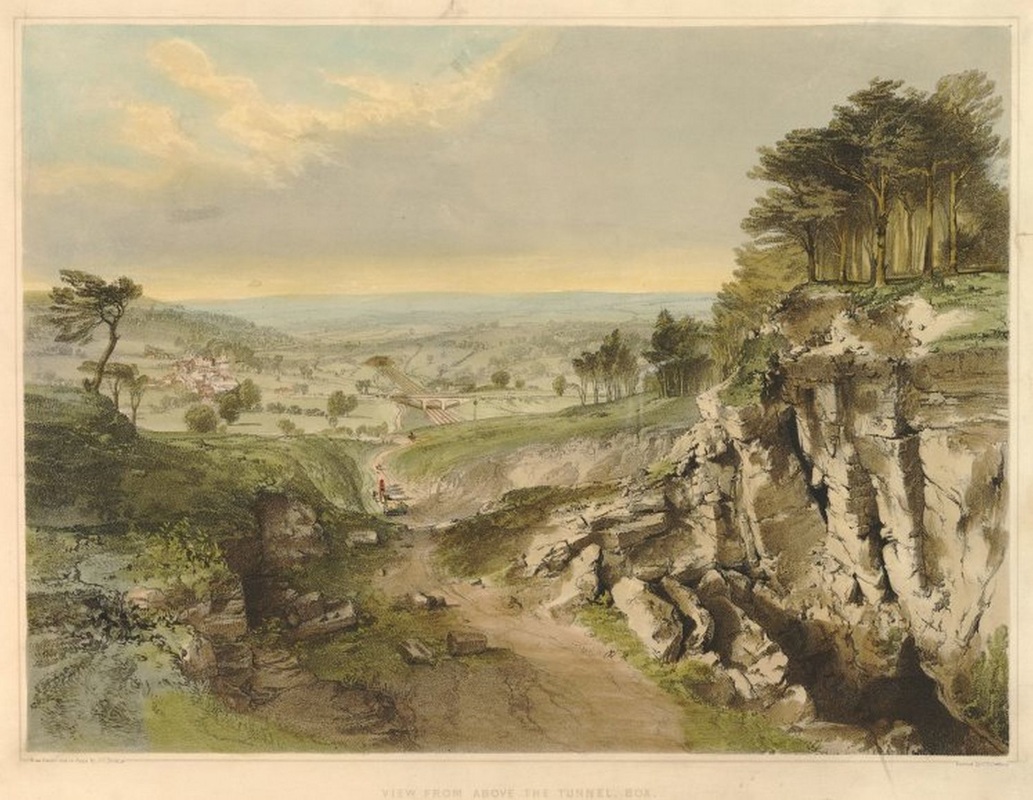

Building Box Tunnel,

1836 to 30 June 1841 Alan Payne September 2016 So much has already been written about this incredible piece of engineering that you may think it is hard to add to the existing knowledge. But you would be wrong and this article seeks to tell the intimate details of Box's tunnel, together with some amazing contemporary reports. One contemporary anecdote is by the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, who complained that the railways would "encourage the lower classes to travel about". |

Foretelling Disaster

Despite Brunel's certainty, there were many others who feared disaster, typical of which was a correspondent in The Bath Chronicle in May 1835 who anticipated a positive, imminent risk to life - to say nothing of the minor evils of utter darkness and concentrated noise.[1] Railway engineer George Stephenson thought that the noise of two trains passing each other in the tunnel would shake the nerves ... No passenger would be induced to go twice.[2]

Opponents claimed Box Tunnel was a health hazard and that trains going through the tunnel: would emerge with a load of corpses, and even if the journey did not prove fatal, no passengers would go twice .. if the brakes failed as the train entered the tunnel it would emerge at 120 mph (a rate at which) no human being could breathe.[3] It was suggested that timid passengers should disembark and use post chaise over Box Hill to avoid the tunnel and The Star road coach advertised its service whereby passengers could join with the eleven o'clock train.[4]

Despite Brunel's certainty, there were many others who feared disaster, typical of which was a correspondent in The Bath Chronicle in May 1835 who anticipated a positive, imminent risk to life - to say nothing of the minor evils of utter darkness and concentrated noise.[1] Railway engineer George Stephenson thought that the noise of two trains passing each other in the tunnel would shake the nerves ... No passenger would be induced to go twice.[2]

Opponents claimed Box Tunnel was a health hazard and that trains going through the tunnel: would emerge with a load of corpses, and even if the journey did not prove fatal, no passengers would go twice .. if the brakes failed as the train entered the tunnel it would emerge at 120 mph (a rate at which) no human being could breathe.[3] It was suggested that timid passengers should disembark and use post chaise over Box Hill to avoid the tunnel and The Star road coach advertised its service whereby passengers could join with the eleven o'clock train.[4]

|

Building Starts

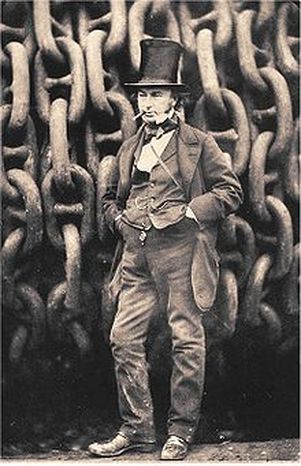

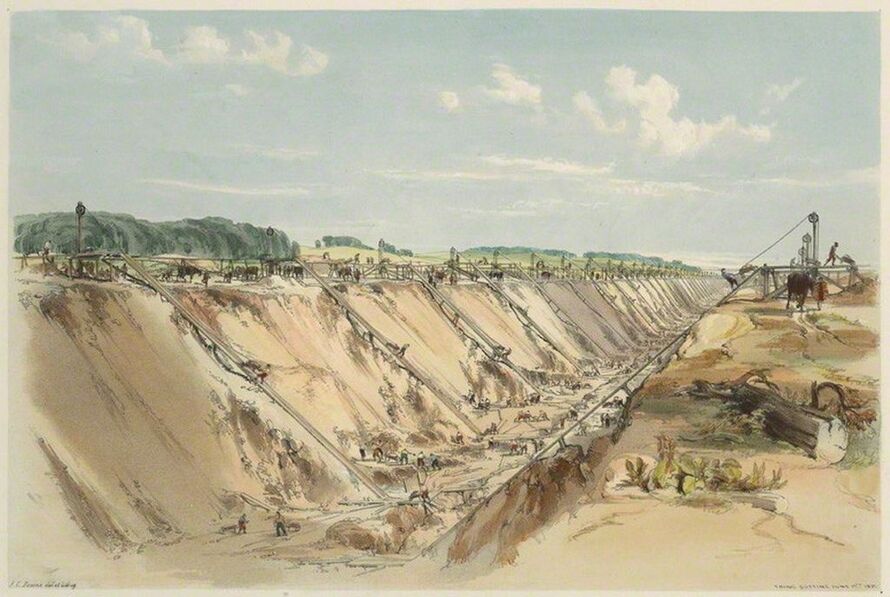

The building of the tunnel was a tremendous task, blasted through by gunpowder, finished off underground by candlelight, and using mostly horse power and human exertion. The invitation to tender was made on 16 August 1837, dividing the work between different sections. The contracts which were placed were very specific: This contract comprehends the excavation of the tunnel and the depositing of materials separating the stone in the manner hereinafter described and the construction of all masonry, brickwork that may be required. Almost two years later contracts were placed with George Burge of Herne Bay to have the western section of 1¼ miles, whilst the more difficult eastern section of ½ mile was allocated to teams under the control of Mr Brewer of Box and Mr Lewis of Bath. Brunel's personal assistant, William Glennie, was in charge of the whole work. Right: Isambard Kingdom Brunel by Robert Howlett, 1857 (courtesy Wikipedia) |

Contractors who Built Box Tunnel

George Burge

Most of the work was undertaken by the contractor George Burge (1795 - 1874) who came from Herne Bay, Kent.[5] He was a very experienced engineer, having worked with Thomas Telford on the construction of St Katharine Docks, London, and with George Stephenson on Britain's first railway tunnel at Tyler Hill, Canterbury, Kent, which Brunel inspected in 1835.[6]

It was quite a coup for the GWR and George Henry Gibbs, a member of the Bristol Society of Merchant Venturers, reported Box Tunnel taken by a respectable contractor.[7]

Contemporary Report by Mr Gale, Foreman for George Burge

Several contemporary reports exist of the work, including the following one by Mr Gale, foreman for Mr Burge.[8] Foreman Gale was on the site for most of the six years that the work took to complete. In his booklet Gale said, Sinking the trial shafts took nearly one year before the contractor commenced sinking the shafts, holes for ventilation and light for the Great Tunnel.

The shafts were sunk 300 feet deep.

Gale was obviously very impressed with his employer, George Burge, whom he described as a very rich and able man of business, who had on hand at the same time the St Catherine (sic) Docks in London and a large job in Germany. He added, Mr Burge had three parts of the tunnel and all his work had to be bricked, so that it was one of the greatest undertakings in this country known up to that time. He did not mention Brunel at all. He goes on to say that over 30 million bricks, made by Mr Hunt at Chippenham, were used to brick up this section of the tunnel. For three years, Mr Hunt employed 100 horses and carts to bring the bricks to Box from Chippenham. For the use of the bricklayers and miners, we had a great quantity of timber from Bath; and from Tanner's Lime Kiln, we had three wagon loads of ashes three or four times a week; and five or six cart loads of lime daily when the weather would permit. This lime kiln appears to have been built on Box Hill to provide mortar for the bricks.[9]

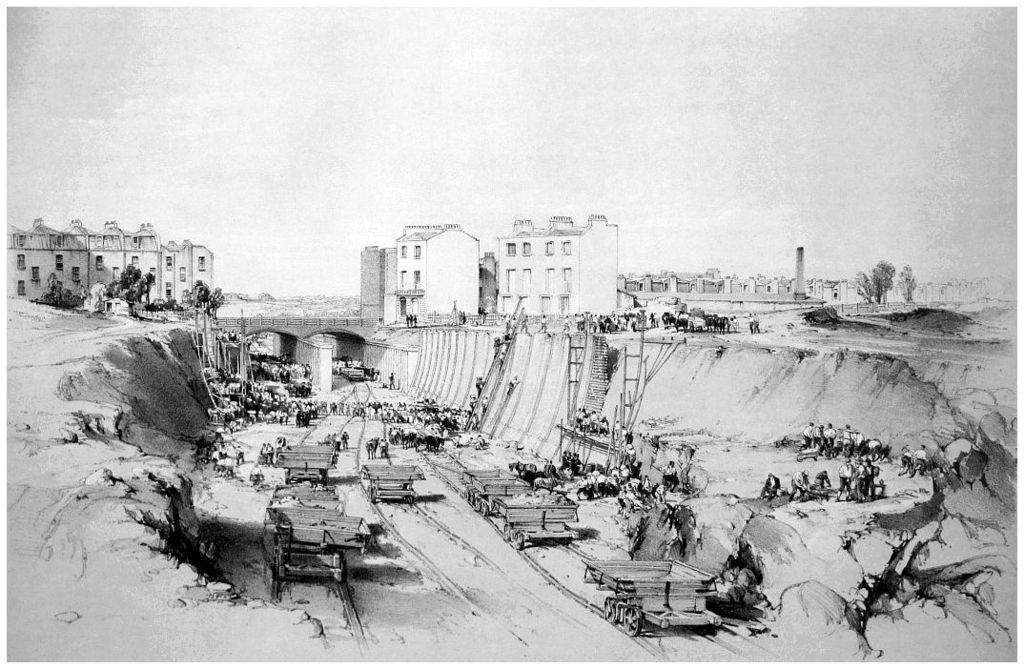

Mr Gale reported that the number of horses engaged at different works in the tunnel could not be less than 300 until the tunnel was finished. It took nearly six years to complete that great undertaking; and every week one ton of gunpowder and one ton of candles were consumed. Work fell behind schedule and by December 1840 Brunel had increased the workforce to 4,000 men. Gale queried, Now the question might be asked: Where did all those men live and sleep? In the neighbouring villages of Box and Corsham and being on day or night duty, as soon as one lot turned out another lot turned in, so that their beds were never empty. Drunkenness and fighting were carried on to an alarming extent. We had 26 inspectors on the works and a portion of them were sent to different villages to keep the peace on Sundays, as well as they could, there being no county police in those days.[10]

George Burge

Most of the work was undertaken by the contractor George Burge (1795 - 1874) who came from Herne Bay, Kent.[5] He was a very experienced engineer, having worked with Thomas Telford on the construction of St Katharine Docks, London, and with George Stephenson on Britain's first railway tunnel at Tyler Hill, Canterbury, Kent, which Brunel inspected in 1835.[6]

It was quite a coup for the GWR and George Henry Gibbs, a member of the Bristol Society of Merchant Venturers, reported Box Tunnel taken by a respectable contractor.[7]

Contemporary Report by Mr Gale, Foreman for George Burge

Several contemporary reports exist of the work, including the following one by Mr Gale, foreman for Mr Burge.[8] Foreman Gale was on the site for most of the six years that the work took to complete. In his booklet Gale said, Sinking the trial shafts took nearly one year before the contractor commenced sinking the shafts, holes for ventilation and light for the Great Tunnel.

The shafts were sunk 300 feet deep.

Gale was obviously very impressed with his employer, George Burge, whom he described as a very rich and able man of business, who had on hand at the same time the St Catherine (sic) Docks in London and a large job in Germany. He added, Mr Burge had three parts of the tunnel and all his work had to be bricked, so that it was one of the greatest undertakings in this country known up to that time. He did not mention Brunel at all. He goes on to say that over 30 million bricks, made by Mr Hunt at Chippenham, were used to brick up this section of the tunnel. For three years, Mr Hunt employed 100 horses and carts to bring the bricks to Box from Chippenham. For the use of the bricklayers and miners, we had a great quantity of timber from Bath; and from Tanner's Lime Kiln, we had three wagon loads of ashes three or four times a week; and five or six cart loads of lime daily when the weather would permit. This lime kiln appears to have been built on Box Hill to provide mortar for the bricks.[9]

Mr Gale reported that the number of horses engaged at different works in the tunnel could not be less than 300 until the tunnel was finished. It took nearly six years to complete that great undertaking; and every week one ton of gunpowder and one ton of candles were consumed. Work fell behind schedule and by December 1840 Brunel had increased the workforce to 4,000 men. Gale queried, Now the question might be asked: Where did all those men live and sleep? In the neighbouring villages of Box and Corsham and being on day or night duty, as soon as one lot turned out another lot turned in, so that their beds were never empty. Drunkenness and fighting were carried on to an alarming extent. We had 26 inspectors on the works and a portion of them were sent to different villages to keep the peace on Sundays, as well as they could, there being no county police in those days.[10]

Lewis and Brewer

In July 1839, the newspaper was able to report that the eastern section had been placed with two independent contractors, Thomas Lewis (1800 - 1858) of Bath and William Jones Brewer (1785 - 1857) of Rudloe Firs. Messrs Lewis and Brewer's contract at the Box Tunnel was couched in glowing terms: One of the greatest obstacles ... of this stupendous undertaking ...

Box Hill, the highest part of which is about 403 feet ... could not be avoided; to make an open cutting through it was impossible.

The extraordinary attempt of boring through this immense mass, consisting in great part of solid beds of freestone was commenced in the summer of 1836 and will be completed in 1841. The main difficulties were in the eastern section towards Corsham from shaft number 8, which is sunk at the proposed mouth of the tunnel on the east side to a point 300 yards towards Shaft number 6 and altogether 2,418 feet from the entrance at the Chippenham end.[10]

At the time of the contract William Jones Brewer was reported as an elderly man, born in the neighbourhood.[11] He had extensive quarry experience and shortly before November 1828 he started excavating the magnificent Cathedral gallery in the

Box Fields Quarry. He later lived at Rudloe Firs, Corsham, with his wife, Jane. It appears that he and Thomas Brewer were working as builders, quarrymen and masons in Corsham and Box until 1837 when they split their partnership.[12] It may be that the Box Tunnel contract was too much of a liability for Thomas Brewer.

Thomas Lewis was a Bath builder, who lived at Wells Road, Bath, from the 1820s up to the 1840s.[13] He was a speculative builder who let out property which he had worked on, including houses at Lansdowne Crescent and Devonshire Buildings and plots at Sydney Gardens.[14] He had undertaken various prestigious works including being paid £1,200 by the Bath Corporation for work on the Abbey in 1836.[15] In 1840 he was advertising for a good draughtsman and accountant.[16] By 1845 he was described as a surveyor and architect, although principally a builder, a person of high character and great respectability.[17] His aspirations continued to grow and he never mentioned his tunnel work, preferring instead to promote his business as Architecture, surveying, estimating and valuing, including civil and ecclesiastical dilapidations.[18] He died 22 November 1858, aged 58, leaving a huge stock of timber and blacksmith materials for sale in his large yard and workshop on the Wells Road.[19]

In July 1839, the newspaper was able to report that the eastern section had been placed with two independent contractors, Thomas Lewis (1800 - 1858) of Bath and William Jones Brewer (1785 - 1857) of Rudloe Firs. Messrs Lewis and Brewer's contract at the Box Tunnel was couched in glowing terms: One of the greatest obstacles ... of this stupendous undertaking ...

Box Hill, the highest part of which is about 403 feet ... could not be avoided; to make an open cutting through it was impossible.

The extraordinary attempt of boring through this immense mass, consisting in great part of solid beds of freestone was commenced in the summer of 1836 and will be completed in 1841. The main difficulties were in the eastern section towards Corsham from shaft number 8, which is sunk at the proposed mouth of the tunnel on the east side to a point 300 yards towards Shaft number 6 and altogether 2,418 feet from the entrance at the Chippenham end.[10]

At the time of the contract William Jones Brewer was reported as an elderly man, born in the neighbourhood.[11] He had extensive quarry experience and shortly before November 1828 he started excavating the magnificent Cathedral gallery in the

Box Fields Quarry. He later lived at Rudloe Firs, Corsham, with his wife, Jane. It appears that he and Thomas Brewer were working as builders, quarrymen and masons in Corsham and Box until 1837 when they split their partnership.[12] It may be that the Box Tunnel contract was too much of a liability for Thomas Brewer.

Thomas Lewis was a Bath builder, who lived at Wells Road, Bath, from the 1820s up to the 1840s.[13] He was a speculative builder who let out property which he had worked on, including houses at Lansdowne Crescent and Devonshire Buildings and plots at Sydney Gardens.[14] He had undertaken various prestigious works including being paid £1,200 by the Bath Corporation for work on the Abbey in 1836.[15] In 1840 he was advertising for a good draughtsman and accountant.[16] By 1845 he was described as a surveyor and architect, although principally a builder, a person of high character and great respectability.[17] His aspirations continued to grow and he never mentioned his tunnel work, preferring instead to promote his business as Architecture, surveying, estimating and valuing, including civil and ecclesiastical dilapidations.[18] He died 22 November 1858, aged 58, leaving a huge stock of timber and blacksmith materials for sale in his large yard and workshop on the Wells Road.[19]

Method of Construction

It was water ingress, and the inability of steam pumps to clear it, from the natural springs in fissures in the rock that had delayed the work. In November 1837 the water increased so fearfully, having filled the tunnel, and risen to the height of 56 feet in the Shaft, as to cause the total suspension of the work till the July following.[21] It happened again the following winter but was cleared more quickly with a second steam pump.

In March 1840 the half-yearly report made poor reading:[22] Very great delay has been caused in all parts of the line ... At the Bristol extremity the floods have interfered ... impossible to carry on the works of the bridges ... four month's additional time will be required for the completion of some of these works ... The situation at Box Hill was no better than elsewhere but three additional shafts had been sunk and from two of them the excavations for the Tunnel are commenced ... about 1,900 yards-run are excavated, 1,220 yards are remaining to be completed.

An unnamed newspaper reporter in July 1839 went down the tunnel and gave interesting details about how it was built.[23] Lewis and Brewer started their men at the shafts at each end and worked towards the centre, when much anxiety was felt lest a straight line should not have been kept ... To the joy of the workmen who took a lively interest in the result and to the triumph of Messrs Lewis and Brewer's scientific working, it was found that the junction was perfectly level. It sounds just like the breakthrough of the Channel Tunnel in 1994. The joining up of the two shafts extended for over 1,520 feet in length and at the junction the utmost deviation from a straight line was only one inch and a quarter.

Being local men and conscious of the number of accidents in the work, Lewis and Brewer had induced the men to contribute to a fund, from which the sick receive 1s a day and those who have met with accidents 1s.6d a day each... this plan has given general satisfaction to the men whose liberal wages enable them by a small sacrifice to provide. No such thing as employer's liability at that time ! You can read a full report of the method of working in the article below.

It was water ingress, and the inability of steam pumps to clear it, from the natural springs in fissures in the rock that had delayed the work. In November 1837 the water increased so fearfully, having filled the tunnel, and risen to the height of 56 feet in the Shaft, as to cause the total suspension of the work till the July following.[21] It happened again the following winter but was cleared more quickly with a second steam pump.

In March 1840 the half-yearly report made poor reading:[22] Very great delay has been caused in all parts of the line ... At the Bristol extremity the floods have interfered ... impossible to carry on the works of the bridges ... four month's additional time will be required for the completion of some of these works ... The situation at Box Hill was no better than elsewhere but three additional shafts had been sunk and from two of them the excavations for the Tunnel are commenced ... about 1,900 yards-run are excavated, 1,220 yards are remaining to be completed.

An unnamed newspaper reporter in July 1839 went down the tunnel and gave interesting details about how it was built.[23] Lewis and Brewer started their men at the shafts at each end and worked towards the centre, when much anxiety was felt lest a straight line should not have been kept ... To the joy of the workmen who took a lively interest in the result and to the triumph of Messrs Lewis and Brewer's scientific working, it was found that the junction was perfectly level. It sounds just like the breakthrough of the Channel Tunnel in 1994. The joining up of the two shafts extended for over 1,520 feet in length and at the junction the utmost deviation from a straight line was only one inch and a quarter.

Being local men and conscious of the number of accidents in the work, Lewis and Brewer had induced the men to contribute to a fund, from which the sick receive 1s a day and those who have met with accidents 1s.6d a day each... this plan has given general satisfaction to the men whose liberal wages enable them by a small sacrifice to provide. No such thing as employer's liability at that time ! You can read a full report of the method of working in the article below.

| lewis_and_brewer_contract_part_1.pdf | |

| File Size: | 544 kb |

| File Type: | |

|

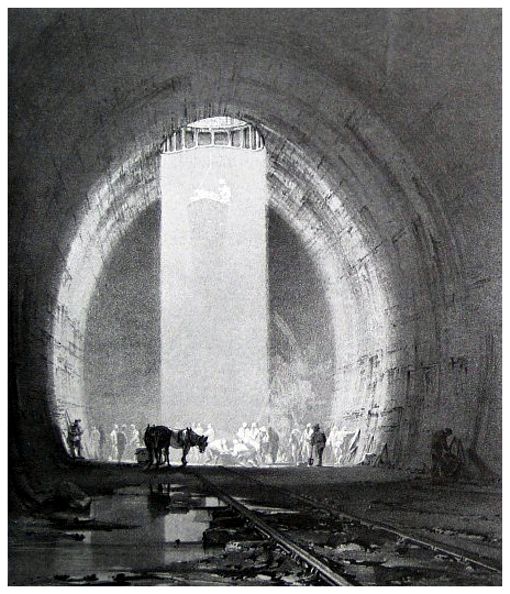

Description of the Work Underground

The reporter gave a marvellous description of the digging of the tunnel. He had been lowered down 136 feet in shaft number 7 on a platform attached to a broad, flat rope, wound and unwound by a steam engine.[24] As far as I am aware this is the only contemporary report of the work during the construction of the tunnel and it makes fascinating reading. There was a constant drip of water from above, a want of free circulation of air and the smell and smoke of gunpowder. On every side there was a dim, dark vault, filled with clouds of vapour, saved from utter and black darkness by the feeble light of candles, which are stuck upon the sides of the excavation. Taking a candle in hand, he picked his way through the pools of water, over the temporary rails, among blocks of stone and the huge chains attached to the machinery ... on the wet and rugged floor. He talked of the many pools and streams with which the floor yet abounds. Right: Interior of Kilsby Tunnel in 1837 by JC Bourne (courtesy Wikipedia) |

When he had a moment he looked up at the roof of the tunnel to admire the solid bed of rock of which it is formed; this part of the tunnel was not lined with brick. He confirmed this again when he said So uninterrupted and compact is the rock through which this end of the tunnel passes that no masonry is required in any part of it - the stone itself forming sides and roof, and nothing being required at the bottom but the rails on which the carriages will run. Brunel himself confirmed this policy in August 1842 when he talked about the way the contractors had extended the height in parts of Box Tunnel to seams of solid beds of Oolitic rock where a perfectly solid and safe roof was afforded by nature.[25] The rock strata was usually between 2½ and 4 feet thick Intersected by vertical fissures.[26] This was an immense depth when it had all to be extracted by hand.

The reporter talked how he came across a strange light, a faint grey streak, coming from an opening above, an unearthly light resembling belated ghosts. It was an air shaft, made to ventilate the tunnel. Occasional rills (small brooks), clear as crystal, came down from fissures in the rocks. When the gunpowder was fired an explosion follows and a concussion such as probably you have never felt before ... the solid rock appears to shake and the reverberation of the sound and shock is ... fearfully experienced. And everywhere were the sounds of the pick, the shovel and the hammer, where gangs of men are at hard work on all sides and the tunnel narrowed to little space at the rock face.

The work was estimated to take three months to complete. In the event it took another two years. To cope with the delays Brunel reputedly increased the workforce to 4,000 men and 300 horses. You can read the full story of the reporter's tour underground in the article below.

The reporter talked how he came across a strange light, a faint grey streak, coming from an opening above, an unearthly light resembling belated ghosts. It was an air shaft, made to ventilate the tunnel. Occasional rills (small brooks), clear as crystal, came down from fissures in the rocks. When the gunpowder was fired an explosion follows and a concussion such as probably you have never felt before ... the solid rock appears to shake and the reverberation of the sound and shock is ... fearfully experienced. And everywhere were the sounds of the pick, the shovel and the hammer, where gangs of men are at hard work on all sides and the tunnel narrowed to little space at the rock face.

The work was estimated to take three months to complete. In the event it took another two years. To cope with the delays Brunel reputedly increased the workforce to 4,000 men and 300 horses. You can read the full story of the reporter's tour underground in the article below.

| lewis_and_brewers_contract_2.doc | |

| File Size: | 30 kb |

| File Type: | doc |

Accidents in Building the Tunnel

The construction of the railway was itself a highly dangerous business but Box Tunnel posed even more problems particularly with the depth underground that men were working. There were over 100 deaths recorded and Brunel's much quoted comment that I think it is a small list considering the heavy work and the amount of powder used ... I am afraid it does not show the whole extent of accidents in that district.[27]

Fatalities and injuries were weekly, mostly individual, incidents.[28] The most common accident was loose stone falling down the shafts. In 1839 a workman having been killed instantaneously by the fall of a stone from the top of shaft number 3.[29] There was also a risk of falling down the open shafts, on the evening of Friday last (30 May) ... at Shaft number 4 at Box Tunnel, a poor man named Robert Price, a native of Bradford, ... unfortunately advanced too near the mouth of the pit, and fell a depth of 296 feet, where he was literally smashed to pieces.[30] There was also the danger of working with gunpowder in dark, underground conditions. In July 1839 a poor fellow (by name of Falkin) not being aware that the match was lighted, advanced too near, when suddenly the mine exploded, and the stone cut his head dreadfully.[31] And in April 1841 the death of a poor man named Stafford, of steady and industrious habits, who was working too close to where others were blasting and a large stone fell upon his head.[32]

There were a smaller number of issues involving heavy equipment, such as that at the engine house of Shaft number 7 when a young man named Sheppard from Atworth, who was possibly intoxicated, went there to lie down and during his slumbers rolled under the sway-beam ... which came down violently on his head and crushed it to pieces.[33]

The lack of central control over the construction of the railway is in contrast to the parliament's involvement in the running of the line. It reflected the desire to have lighter controls, mirrored in the economic term laissez faire (let it be). Contemporaries were aware that the loss of life was unacceptable but they placed the blame on the workmen rather than the GWR company: Many of these fatal accidents might have been prevented by a more cautious line of proceeding, during the excavations, by the workmen.[34] Of course, for every death there were as many people disabled by accidents, such as during a fortnight in November 1840 when three men lost their lives and two others have had their limbs dreadfully mangled.[35]

It is reputed that the Tunnel Inn heard the inquests of many of these men but it has never been determined where they were buried.[36] By contrast, Middlehill Tunnel from Bath to the west mouth of the Box Tunnel was a much simpler task with the total contents of the cuttings on this distance of 7½ miles ... with a short tunnel of 200 yards.[37]

There was also a risk to travellers through rockfalls and contemporaries were divided over the need to line the tunnel with bricks. The eminent geologist Professor William Buckland of Oxford University, and twice president of the Geology Society, argued fiercely in favour of supporting the roof and the whole western section built by George Burge was lined. On the western side the entrance was supported and only sections of the tunnel were lined and even to this day some of the tunnel remains unlined.

The construction of the railway was itself a highly dangerous business but Box Tunnel posed even more problems particularly with the depth underground that men were working. There were over 100 deaths recorded and Brunel's much quoted comment that I think it is a small list considering the heavy work and the amount of powder used ... I am afraid it does not show the whole extent of accidents in that district.[27]

Fatalities and injuries were weekly, mostly individual, incidents.[28] The most common accident was loose stone falling down the shafts. In 1839 a workman having been killed instantaneously by the fall of a stone from the top of shaft number 3.[29] There was also a risk of falling down the open shafts, on the evening of Friday last (30 May) ... at Shaft number 4 at Box Tunnel, a poor man named Robert Price, a native of Bradford, ... unfortunately advanced too near the mouth of the pit, and fell a depth of 296 feet, where he was literally smashed to pieces.[30] There was also the danger of working with gunpowder in dark, underground conditions. In July 1839 a poor fellow (by name of Falkin) not being aware that the match was lighted, advanced too near, when suddenly the mine exploded, and the stone cut his head dreadfully.[31] And in April 1841 the death of a poor man named Stafford, of steady and industrious habits, who was working too close to where others were blasting and a large stone fell upon his head.[32]

There were a smaller number of issues involving heavy equipment, such as that at the engine house of Shaft number 7 when a young man named Sheppard from Atworth, who was possibly intoxicated, went there to lie down and during his slumbers rolled under the sway-beam ... which came down violently on his head and crushed it to pieces.[33]

The lack of central control over the construction of the railway is in contrast to the parliament's involvement in the running of the line. It reflected the desire to have lighter controls, mirrored in the economic term laissez faire (let it be). Contemporaries were aware that the loss of life was unacceptable but they placed the blame on the workmen rather than the GWR company: Many of these fatal accidents might have been prevented by a more cautious line of proceeding, during the excavations, by the workmen.[34] Of course, for every death there were as many people disabled by accidents, such as during a fortnight in November 1840 when three men lost their lives and two others have had their limbs dreadfully mangled.[35]

It is reputed that the Tunnel Inn heard the inquests of many of these men but it has never been determined where they were buried.[36] By contrast, Middlehill Tunnel from Bath to the west mouth of the Box Tunnel was a much simpler task with the total contents of the cuttings on this distance of 7½ miles ... with a short tunnel of 200 yards.[37]

There was also a risk to travellers through rockfalls and contemporaries were divided over the need to line the tunnel with bricks. The eminent geologist Professor William Buckland of Oxford University, and twice president of the Geology Society, argued fiercely in favour of supporting the roof and the whole western section built by George Burge was lined. On the western side the entrance was supported and only sections of the tunnel were lined and even to this day some of the tunnel remains unlined.

Railway Navvies

It has often been reported that the influx of railway navvies (navigators) caused great fear of lawlessness and violence.[38]

The navvies flooded into the village in search of the high wages, bringing overcrowding and poor housing conditions. They took up all available lodgings and set up encampments around the tunnel workings, living a life of drink, tommy shops ( a shop run by a contractor where his tokens could be exchanged for goods or beer) and fighting amongst themselves and sometimes with village people. The arrival of so many labourers attracted disreputable followers including prostitutes, some of whom were prosecuted for exposing themselves in the street. A local inhabitant, complaining of theft of garden produce, gave evidence that he was unable to keep anything, being so near as I am to the line of the railroad. But how true were these fears?

It has often been reported that the influx of railway navvies (navigators) caused great fear of lawlessness and violence.[38]

The navvies flooded into the village in search of the high wages, bringing overcrowding and poor housing conditions. They took up all available lodgings and set up encampments around the tunnel workings, living a life of drink, tommy shops ( a shop run by a contractor where his tokens could be exchanged for goods or beer) and fighting amongst themselves and sometimes with village people. The arrival of so many labourers attracted disreputable followers including prostitutes, some of whom were prosecuted for exposing themselves in the street. A local inhabitant, complaining of theft of garden produce, gave evidence that he was unable to keep anything, being so near as I am to the line of the railroad. But how true were these fears?

In reality, the main crime was theft from the railway construction companies, not from residents. Local anecdote has it that the problem was so bad Box Candle Factory inserted coloured cotton thread in its candles to identify them. Nor was it only the navvies who caused riotous behaviour. The amount of crime was already high in an age of violence. In the years before the railway, gang masters supplied cheap agricultural labour who often caused trouble.[39] In 1822 Box Revels resulted in a prosecution at Marlborough Quarter Sessions when local men were charged with an assault on the Constable. The revelry was held despite attempts to abolish it in 1779 for riotous conduct.[40]

Drunkenness was a recurring problem and at Kingsdown Fair in September 1839 a mob of about 70 people, including navvies and other villagers, went around demanding money or smashing the stalls. William Burton, himself a navvy, was sitting in the beer tent drinking at about midnight when two men entered, stole 1s from him and beat him up.[41] I was beaten so much, William told the court, that I could not walk - I crawled away and went home.

The village authorities attempted to deal with the problem. Police duties had previously been the responsibility of the parish vestry and the parish constable. In the 1830s a private association was formed for the prosecution of criminals, which held court at the Clock House (now the site of the Co-operative shop). Between 1831 and 1836, twelve Assize Courts and five Quarter Sessions were held there. Further efforts were made to restrict crime after 1839, when the Rural Police Act set up paid, full-time and uniformed police in country areas. In July 1839 the police chased a navvy called Ginger in the fields over Box Tunnel until they were attacked by a group of railway labourers and hay makers led by a ferocious woman armed with a rake.

Punishment was severe and convicted felons could expect little mercy. It was an age when public execution was for a long time the prescribed punishment for shoplifting as a deterrent to others.[42] Locally a group of navvies was charged with causing an affray and damage to a contractor who had not paid them. They were sentenced to transportation for terms up to 15 years. William C, aged 21, was found guilty of burglary at Corsham and sentenced to death.[43]

Drunkenness was a recurring problem and at Kingsdown Fair in September 1839 a mob of about 70 people, including navvies and other villagers, went around demanding money or smashing the stalls. William Burton, himself a navvy, was sitting in the beer tent drinking at about midnight when two men entered, stole 1s from him and beat him up.[41] I was beaten so much, William told the court, that I could not walk - I crawled away and went home.

The village authorities attempted to deal with the problem. Police duties had previously been the responsibility of the parish vestry and the parish constable. In the 1830s a private association was formed for the prosecution of criminals, which held court at the Clock House (now the site of the Co-operative shop). Between 1831 and 1836, twelve Assize Courts and five Quarter Sessions were held there. Further efforts were made to restrict crime after 1839, when the Rural Police Act set up paid, full-time and uniformed police in country areas. In July 1839 the police chased a navvy called Ginger in the fields over Box Tunnel until they were attacked by a group of railway labourers and hay makers led by a ferocious woman armed with a rake.

Punishment was severe and convicted felons could expect little mercy. It was an age when public execution was for a long time the prescribed punishment for shoplifting as a deterrent to others.[42] Locally a group of navvies was charged with causing an affray and damage to a contractor who had not paid them. They were sentenced to transportation for terms up to 15 years. William C, aged 21, was found guilty of burglary at Corsham and sentenced to death.[43]

|

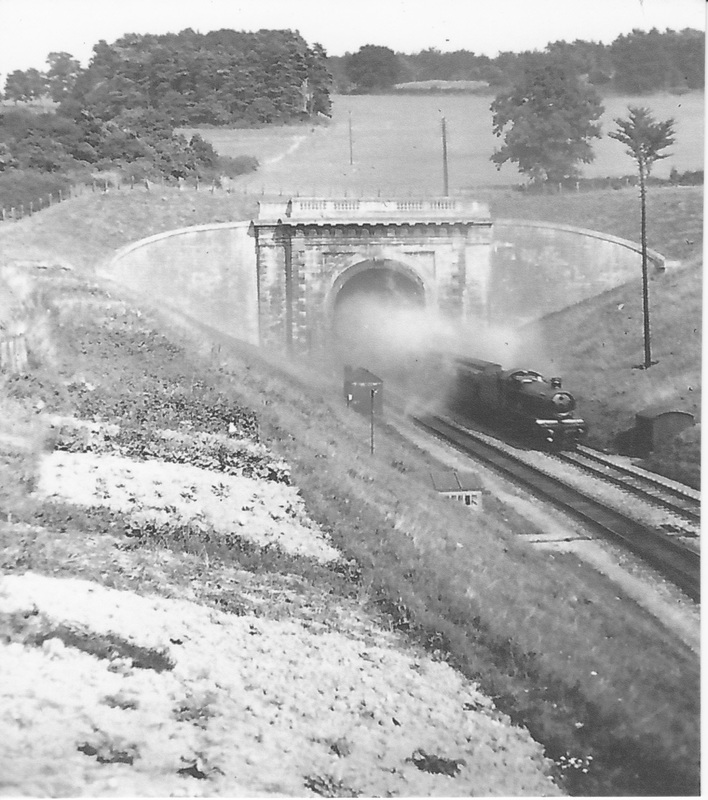

Opening Day, 30 June 1841

The opening of the line was recalled as the greatest public work ... constructed in this or any country by an incorporated body.[44] The first train to attempt the climb was The Meridian driven by Cuthbert Davison with Brunel on board but the track had not been completed and, they had to wait for four hours whilst navvies made a crossover track from the up to the down line in order to finish the journey.[45] There was still some doubt about its viability and the famous Swindon engineer, Daniel Gooch, agreed to travel on the train for the first couple of days. He recorded details in a diary and of the near catastrophe that occurred.[46] His report makes fascinating reading: 1841 The whole of the Great Western Railway between London and Bristol was opened on the 30 June 1841, and the question of working through the Box Tunnel up a gradient of 1 in 100 was a source of much anxiety to Mr Brunel. I cannot say I felt any anxiety; I had seen how well our engines took their loads up Wootton Bassett without the help of a bank engine, and with the assistance of a bank engine at Box I felt we would have no difficulty. |

Only one line of rails was completed through the tunnel the day we opened, and the trains had therefore to be worked on a single line. I undertook to accompany all the trains through the tunnel and did so the first day and night, also the second day, intending to be relieved when the mail came down on the second night at about 11 o'clock.

That night we had a very narrow escape of a fearful accident. I was going up the tunnel with the last up train when I fancied I saw some green lights, placed as they were in front of our trains. A second's reflection convinced me it was the mail coming down. I lost no time in reversing the engine I was on and running back to Box Station with my train as quickly as I could, when the mails came down close behind me. The policeman at the top of the tunnel had made some blunder and sent the mails on when they arrived there. Had the tunnel not been pretty clear of steam we must have met in full career and the smash would have been fearful, cutting short my career also.

But as though mishaps never came alone, when I was taking my train up again, from some cause or other the engine got off the rails in the tunnel, and I was detained there all night before I got all straight again. Box Tunnel had a very pretty effect for the couple of days it was worked as a single line, from the number of candles used by the men working on the unfinished line. It was a perfect illumination extending through the whole tunnel nearly two miles long.

The directors of GWR made a journey from London Paddington to Bristol later on 30 June 1841 when the tunnel was decorated.[47]

The advent was celebrated by a day's rejoicing in Box and upwards of 100 flags decorated the tunnel mouth, banks and bridge. Close by was a band of music playing and three hogsheads of beer (1,200 pints) were given away by me on behalf of the company. On the same day several thousands of people came from all parts to witness the scene. In the evening we had an entertainment at the Queen's Head for the principal men of the tunnel. For its initial public service the Company ran eight passenger and two goods trains (which also included third class accommodation) per day in each direction and the journey from London to Bristol took 4 hours 10 minutes at an average speed of 28 miles per hour.[48] The reputed cost of the entire line was estimated as £13 million.[49]

On completion Box Tunnel was 2,964 metres long, the longest in the world at that time. It was the wonder of the age as can be seen from an 1841 report: On Wednesday this magnificent Railway was opened ... Now, after very great difficulties and impediments, the tunnel has been completed ... and it will remain a wonderful monument of the powers of human intellect and industry... persons will be able to travel from London to Bristol in about four hours - 120 miles in four hours! [50]

That night we had a very narrow escape of a fearful accident. I was going up the tunnel with the last up train when I fancied I saw some green lights, placed as they were in front of our trains. A second's reflection convinced me it was the mail coming down. I lost no time in reversing the engine I was on and running back to Box Station with my train as quickly as I could, when the mails came down close behind me. The policeman at the top of the tunnel had made some blunder and sent the mails on when they arrived there. Had the tunnel not been pretty clear of steam we must have met in full career and the smash would have been fearful, cutting short my career also.

But as though mishaps never came alone, when I was taking my train up again, from some cause or other the engine got off the rails in the tunnel, and I was detained there all night before I got all straight again. Box Tunnel had a very pretty effect for the couple of days it was worked as a single line, from the number of candles used by the men working on the unfinished line. It was a perfect illumination extending through the whole tunnel nearly two miles long.

The directors of GWR made a journey from London Paddington to Bristol later on 30 June 1841 when the tunnel was decorated.[47]

The advent was celebrated by a day's rejoicing in Box and upwards of 100 flags decorated the tunnel mouth, banks and bridge. Close by was a band of music playing and three hogsheads of beer (1,200 pints) were given away by me on behalf of the company. On the same day several thousands of people came from all parts to witness the scene. In the evening we had an entertainment at the Queen's Head for the principal men of the tunnel. For its initial public service the Company ran eight passenger and two goods trains (which also included third class accommodation) per day in each direction and the journey from London to Bristol took 4 hours 10 minutes at an average speed of 28 miles per hour.[48] The reputed cost of the entire line was estimated as £13 million.[49]

On completion Box Tunnel was 2,964 metres long, the longest in the world at that time. It was the wonder of the age as can be seen from an 1841 report: On Wednesday this magnificent Railway was opened ... Now, after very great difficulties and impediments, the tunnel has been completed ... and it will remain a wonderful monument of the powers of human intellect and industry... persons will be able to travel from London to Bristol in about four hours - 120 miles in four hours! [50]

References

[1] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, 2003, Sutton Publishing, p.1

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 19 July 1906

[3] Roy Chadwick and Martin C. Knights, The Story of Tunnels, 1988, Andre Deutsch Ltd, p.40

[4] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 7 June 1941

[5] http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/George_Burge

[6] http://www.kentrail.org.uk/tyler_hill_tunnel.htm

[7] George Henry Gibbs, The Birth of the Great Western Railway, 1971, Adams & Dart, 22 February 1838

[8] Reproduced from Chippenham News March 1983, based on a pamphlet owned by Mr Stevens

[9] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, 2003, Sutton Publishing, p.18

[10] Gale went on to become an office porter with GWR and was at Bath from 1852 until 1880 when ill health forced him to retire.

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 18 July 1839

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 9 August 1842

[13] Perry's Bankrupt Gazette, 28 April 1837

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 10 May 1821

[15] The Bath Chronicle, 28 May 1829 and 6 February 1834

[16] The Bath Chronicle, 14 January 1836

[17] The Bath Chronicle, 30 July 1840

[18] The Bath Chronicle, 10 April 1845

[19] The Bath Chronicle, 3 April 1851

[20] The Bath Chronicle, 25 November 1858

[21] The Bath Chronicle, 18 July 1839

[22] The Bath Chronicle, 5 March 1840

[23] The Bath Chronicle, 18 July 1839

[24] The Bath Chronicle, 18 July 1839

[25] The Bath Chronicle, 25 August 1842

[26] The Bath Chronicle, 9 August 1842

[27] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire an Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.43

[28] The Bath Chronicle, 9 April 1840

[29] The Bath Chronicle, 6 June 1839

[30] The Bath Chronicle, 20 February 1840

[31] The Bath Chronicle, 11 July 1839

[32] The Bath Chronicle, 15 April 1841

[33] The Bath Chronicle, 30 July 1840

[34] The Bath Chronicle, 6 June 1839

[35] The Bath Chronicle, 5 November 1840

[36] The Evening Post, 11 April 1972

[37] The Bath Chronicle, 5 September 1839

[38] This section is indebted to David Brooke, The 'Lawless' Navvy, 1989, The Journal of Transport History, Volume 10, number 2

[39] Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066-1945, 1987, Harper Collins, p.559

[40] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire an Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.20

[41] David Brooke, The 'Lawless' Navvy, 1989, The Journal of Transport History, Volume 10, number 2

[42] Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066-1945, 1987, Harper Collins p.661

[43] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, 1989, pub John Poulsom, p.12

[44] The Bath Chronicle, 8 July 1841

[45] Alan Platt, The Life and Times of Daniel Gooch, 1987, Alan Sutton, p.55 and Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p.30

[46] Daniel Gooch, The Diaries of Sir Daniel Gooch, 1972, David & Charles, p.42

[47] Memories recorded by Mr Gale, foreman to George Burge, Reproduced from Chippenham News March 1983, based on a pamphlet owned by Mr Stevens

[48] Alan Platt, The Life and Times of Daniel Gooch, 1987, Alan Sutton, p.56

[49] MC Corfield, A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Wiltshire, 1978, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, p.18

[50] CJ Hall, Corsham: An Illustrated History, CJ Hall Publisher, p.12

[1] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, 2003, Sutton Publishing, p.1

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 19 July 1906

[3] Roy Chadwick and Martin C. Knights, The Story of Tunnels, 1988, Andre Deutsch Ltd, p.40

[4] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 7 June 1941

[5] http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/George_Burge

[6] http://www.kentrail.org.uk/tyler_hill_tunnel.htm

[7] George Henry Gibbs, The Birth of the Great Western Railway, 1971, Adams & Dart, 22 February 1838

[8] Reproduced from Chippenham News March 1983, based on a pamphlet owned by Mr Stevens

[9] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, 2003, Sutton Publishing, p.18

[10] Gale went on to become an office porter with GWR and was at Bath from 1852 until 1880 when ill health forced him to retire.

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 18 July 1839

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 9 August 1842

[13] Perry's Bankrupt Gazette, 28 April 1837

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 10 May 1821

[15] The Bath Chronicle, 28 May 1829 and 6 February 1834

[16] The Bath Chronicle, 14 January 1836

[17] The Bath Chronicle, 30 July 1840

[18] The Bath Chronicle, 10 April 1845

[19] The Bath Chronicle, 3 April 1851

[20] The Bath Chronicle, 25 November 1858

[21] The Bath Chronicle, 18 July 1839

[22] The Bath Chronicle, 5 March 1840

[23] The Bath Chronicle, 18 July 1839

[24] The Bath Chronicle, 18 July 1839

[25] The Bath Chronicle, 25 August 1842

[26] The Bath Chronicle, 9 August 1842

[27] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire an Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.43

[28] The Bath Chronicle, 9 April 1840

[29] The Bath Chronicle, 6 June 1839

[30] The Bath Chronicle, 20 February 1840

[31] The Bath Chronicle, 11 July 1839

[32] The Bath Chronicle, 15 April 1841

[33] The Bath Chronicle, 30 July 1840

[34] The Bath Chronicle, 6 June 1839

[35] The Bath Chronicle, 5 November 1840

[36] The Evening Post, 11 April 1972

[37] The Bath Chronicle, 5 September 1839

[38] This section is indebted to David Brooke, The 'Lawless' Navvy, 1989, The Journal of Transport History, Volume 10, number 2

[39] Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066-1945, 1987, Harper Collins, p.559

[40] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire an Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.20

[41] David Brooke, The 'Lawless' Navvy, 1989, The Journal of Transport History, Volume 10, number 2

[42] Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066-1945, 1987, Harper Collins p.661

[43] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, 1989, pub John Poulsom, p.12

[44] The Bath Chronicle, 8 July 1841

[45] Alan Platt, The Life and Times of Daniel Gooch, 1987, Alan Sutton, p.55 and Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p.30

[46] Daniel Gooch, The Diaries of Sir Daniel Gooch, 1972, David & Charles, p.42

[47] Memories recorded by Mr Gale, foreman to George Burge, Reproduced from Chippenham News March 1983, based on a pamphlet owned by Mr Stevens

[48] Alan Platt, The Life and Times of Daniel Gooch, 1987, Alan Sutton, p.56

[49] MC Corfield, A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Wiltshire, 1978, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, p.18

[50] CJ Hall, Corsham: An Illustrated History, CJ Hall Publisher, p.12