Britain in Late Antiquity Period Alan Payne and Jonathan Parkhouse, June 2020

Cassell's Illustrated History of England proclaimed in 1865: "After the departure of the Romans, the Britons were left to contend as best they could against the hordes of (Saxon) invaders accompanied by the kindred nations known as the Jutes and Angles". Until after the Second World War, this narrative was the accepted version of our national story supported by the concept of the "Dark Ages" to explain various inconsistencies.

Now we can draft a more coherent and inclusive narrative of this period. In this article we trace new interpretations of this story with particular attention to archaeological and DNA research over the last 20 years set alongside the existing narrative record. This offers a completely different interpretation.[1]

Now we can draft a more coherent and inclusive narrative of this period. In this article we trace new interpretations of this story with particular attention to archaeological and DNA research over the last 20 years set alongside the existing narrative record. This offers a completely different interpretation.[1]

Life in the Late Roman Period

It is indisputable that the Romanised style of life in Britain disappeared in the two centuries after AD 350. The period is sometimes described as sub-Roman (meaning a lesser version of Roman rule) or late antiquity (which emphasises the continuity of the evolution of society). The latter description seems to be the most appropriate for our area where we see the continuance of many aspects of Roman lifestyle in and around Bath. Because of its proximity to the city, we might surmise that Box was influenced by the way that Bath developed, gradually evolving over time into a different cultural and social basis, rather than the sudden change envisaged in the headline illustration.

Significant change had started in local areas by about AD 350. The outer precinct of the Temple of Sulis Minerva, Bath, appears to have collapsed and been abandoned in favour of secular buildings and the inner colonnade dismantled, with parts of the floor covered in silt and rubbish under a layer of cobbles.[2] By 375 change was well under way. There was a late burst of what looks like prosperity, or at least a conspicuous display of wealth, in South West Britain in mid-300s, with the villa economy still intact and a local school of mosaicists at work. In Wiltshire there may have been a resurgence of pagan (in the sense of non-Christian) ritual. But urban life had seen significant change much earlier. The eastern entrance of the Bath Temple was demolished and the sacrificial altar dismantled in the mid-380s, possibly indicating a substantial change in religious observance.[3]

The changes affected every aspect of life. The economy had already begun to contract after AD 375, parts of the army were withdrawn in 383, public buildings were not repaired at Exeter, although Bath probably fared better. Rebel emperors named Marcus and Gratian were declared in Britain in the early 400s.[4] The army appointed a soldier as Emperor Constantine III in 406 who led British troops into Gaul (until he was killed in battle in 411) and the Emperor Honorius rejected a British appeal for military help in 410.[5]

It is indisputable that the Romanised style of life in Britain disappeared in the two centuries after AD 350. The period is sometimes described as sub-Roman (meaning a lesser version of Roman rule) or late antiquity (which emphasises the continuity of the evolution of society). The latter description seems to be the most appropriate for our area where we see the continuance of many aspects of Roman lifestyle in and around Bath. Because of its proximity to the city, we might surmise that Box was influenced by the way that Bath developed, gradually evolving over time into a different cultural and social basis, rather than the sudden change envisaged in the headline illustration.

Significant change had started in local areas by about AD 350. The outer precinct of the Temple of Sulis Minerva, Bath, appears to have collapsed and been abandoned in favour of secular buildings and the inner colonnade dismantled, with parts of the floor covered in silt and rubbish under a layer of cobbles.[2] By 375 change was well under way. There was a late burst of what looks like prosperity, or at least a conspicuous display of wealth, in South West Britain in mid-300s, with the villa economy still intact and a local school of mosaicists at work. In Wiltshire there may have been a resurgence of pagan (in the sense of non-Christian) ritual. But urban life had seen significant change much earlier. The eastern entrance of the Bath Temple was demolished and the sacrificial altar dismantled in the mid-380s, possibly indicating a substantial change in religious observance.[3]

The changes affected every aspect of life. The economy had already begun to contract after AD 375, parts of the army were withdrawn in 383, public buildings were not repaired at Exeter, although Bath probably fared better. Rebel emperors named Marcus and Gratian were declared in Britain in the early 400s.[4] The army appointed a soldier as Emperor Constantine III in 406 who led British troops into Gaul (until he was killed in battle in 411) and the Emperor Honorius rejected a British appeal for military help in 410.[5]

About 540 the British monk Gildas (about 500-570) wrote a sermon about the collapse of Christian morality and The Groans of the Britons: The barbarians drive us to the sea; the sea throws us back on the barbarians: thus two modes of death await us, we are either slain or drowned.[6] A fire heaped up by the impious easterners spread from sea to sea. It devastated town and country round about, and, once it was alight, it did not die down until it had burned almost the whole of the island. Nowadays Gildas’ comments are often interpreted as sermonising rather than a straightforward historic record. Many of the words he uses are subjective and have different connotations in modern English usage, including the words barbarians, impious and devastated.

As much as change, he records the continuance of a modified Romanised lifestyle with a functioning legal system and ecclesiastical hierarchy, albeit with differences occurring in religious observance.

As much as change, he records the continuance of a modified Romanised lifestyle with a functioning legal system and ecclesiastical hierarchy, albeit with differences occurring in religious observance.

Was There a Decline in Late Roman Period?

Edward Gibbon's best-known work, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, has cast a long shadow in our interpretation of our history since it was first published in 1776. The Georgian period was the age which invented the word civilisation as a concept in political economy, describing an enlightened society which made things civil, from which flowed social order and manners. Architecture and statues from the Georgian period show a fascination with dressing up as Romans, and the symbolism resonated well with their age of imperialism and colonialism. The fall of the Romans was expressed entirely in negative terms, with the model of a civilised Roman order being swept away by Germanic barbarians becoming deeply embedded in our psyche. Historians and archaeologists are now both challenging this.

We can also see some pronounced social and economic developments in this period. With the Romans no longer exacting taxes, there was probably less need to produce a farming surplus. Roman roads deteriorated and travel and trade reduced. The Plagues of Justinian in the 500s may have caused dramatic population decline and economic activity sank into subsistence levels of agriculture. Coinage became more limited in circulation and, where found, appears to have a different function, held as bullion for its value rather than as currency for exchange and in its place there was greater local use of barter. On the other hand, Germanic influences around Bath do not appear to have taken hold until the late 600s. A charter of 601 by a British king suggests that the area south of the West Wansdyke remained in Romano-British hands after the Battle of Dyrham in 577.[7]

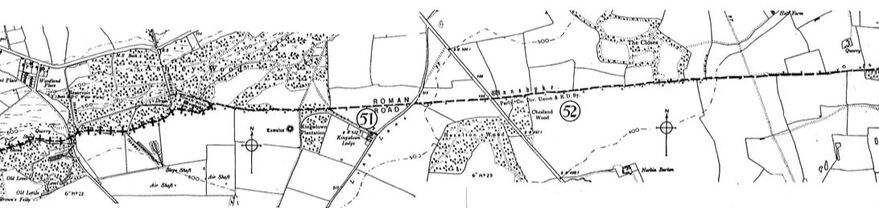

We can speculate on events in Britain at this time. Removal of state control may have encouraged diversification of agriculture from intensive arable to regimes which more closely met local needs. The environmental evidence seems to show a shift to less intensive agricultural regimes, entirely possible once the surpluses were no longer squeezed by the demands of the empire, with arable giving way to increased reliance upon pastoralism, especially sheep. The cultivation of spelt (a species of wheat) certainly ceased after the Roman period. There seems to have been an increase in a diet of animal protein and a concomitant fall in carbohydrates. The change would likely lead to improved health with higher average height and better dental health. But conversion to pasture didn’t mean abandonment of the landscape and a block of fields adjacent to the Roman road at Gastard, Corsham appears to be of Romano-British origin.[8]

Edward Gibbon's best-known work, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, has cast a long shadow in our interpretation of our history since it was first published in 1776. The Georgian period was the age which invented the word civilisation as a concept in political economy, describing an enlightened society which made things civil, from which flowed social order and manners. Architecture and statues from the Georgian period show a fascination with dressing up as Romans, and the symbolism resonated well with their age of imperialism and colonialism. The fall of the Romans was expressed entirely in negative terms, with the model of a civilised Roman order being swept away by Germanic barbarians becoming deeply embedded in our psyche. Historians and archaeologists are now both challenging this.

We can also see some pronounced social and economic developments in this period. With the Romans no longer exacting taxes, there was probably less need to produce a farming surplus. Roman roads deteriorated and travel and trade reduced. The Plagues of Justinian in the 500s may have caused dramatic population decline and economic activity sank into subsistence levels of agriculture. Coinage became more limited in circulation and, where found, appears to have a different function, held as bullion for its value rather than as currency for exchange and in its place there was greater local use of barter. On the other hand, Germanic influences around Bath do not appear to have taken hold until the late 600s. A charter of 601 by a British king suggests that the area south of the West Wansdyke remained in Romano-British hands after the Battle of Dyrham in 577.[7]

We can speculate on events in Britain at this time. Removal of state control may have encouraged diversification of agriculture from intensive arable to regimes which more closely met local needs. The environmental evidence seems to show a shift to less intensive agricultural regimes, entirely possible once the surpluses were no longer squeezed by the demands of the empire, with arable giving way to increased reliance upon pastoralism, especially sheep. The cultivation of spelt (a species of wheat) certainly ceased after the Roman period. There seems to have been an increase in a diet of animal protein and a concomitant fall in carbohydrates. The change would likely lead to improved health with higher average height and better dental health. But conversion to pasture didn’t mean abandonment of the landscape and a block of fields adjacent to the Roman road at Gastard, Corsham appears to be of Romano-British origin.[8]

|

Gildas the Wise Gildas was a Romano-British monk famous for his Biblical knowledge. Probably the younger son of a British king, in later life he founded a monastery in Brittany and died there in AD 570. |

Narrative sources do not all point to chaos and collapse.

St Germanus visited Britain to suppress an outbreak of heresy in the British church in 429 and seemed to describe a place which was prosperous and stable. St Patrick seemed to take for granted an orderly situation in the west of Britain at a similar period. Even Gildas seemed to describe a functioning legal system and ecclesiastical hierarchy. |

Burial and Cultural Changes

Whilst the documentary sources present a confusing picture, archaeological evidence of funerial customs seem (initially) to be straightforward. Practices of inhumation (burial of the bodies of deceased) or urned cremation with coins and luxuries (both prevalent in Roman culture) gave way to burials with belongings needed for the afterlife, such as swords and sewing tools. The change is marked sharply in south and east Britain at the start of the 400s but not in the west where Romano-British practices continued until substantially later perhaps AD 600 in north-western Wiltshire.[9] Some historians used to say that people were Romano-British, Germanic, Scandinavian or Saxon on the basis of what they were buried with or the orientation of their grave. The same applied to supposed pagan or Christian burials based on the presence or absence of grave goods, notwithstanding that grave goods may not have been incompatible with Christianity. Identification of ethnicity from funerary data is a highly problematic area. Definition of British and Germanic individuals on the basis of grave goods gives rise to self-reinforcing arguments. A particular set of grave goods does not mean a particular origin; indeed, ethnicity is a social rather than a biological construct. Isotope studies are now showing the mixed origins of groups of people in the same cemeteries and with the same grave goods.

Whilst the documentary sources present a confusing picture, archaeological evidence of funerial customs seem (initially) to be straightforward. Practices of inhumation (burial of the bodies of deceased) or urned cremation with coins and luxuries (both prevalent in Roman culture) gave way to burials with belongings needed for the afterlife, such as swords and sewing tools. The change is marked sharply in south and east Britain at the start of the 400s but not in the west where Romano-British practices continued until substantially later perhaps AD 600 in north-western Wiltshire.[9] Some historians used to say that people were Romano-British, Germanic, Scandinavian or Saxon on the basis of what they were buried with or the orientation of their grave. The same applied to supposed pagan or Christian burials based on the presence or absence of grave goods, notwithstanding that grave goods may not have been incompatible with Christianity. Identification of ethnicity from funerary data is a highly problematic area. Definition of British and Germanic individuals on the basis of grave goods gives rise to self-reinforcing arguments. A particular set of grave goods does not mean a particular origin; indeed, ethnicity is a social rather than a biological construct. Isotope studies are now showing the mixed origins of groups of people in the same cemeteries and with the same grave goods.

|

The issue then becomes how to interpret different cultural practices – put simply, were they externally imposed or were they a reaction to changed internal circumstances? The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was for a long time the accepted, sole version of events. According to the Chronicle, one of the invading Germanic tribes, called the Gewisse, gradually made incursions from their power base in the Upper Thames Valley into Wiltshire following victory against the Britons at Searobyrig (Old Sarum, Salisbury) in 552 and Beranbyrig (possibly identified as Barbary Castle, Swindon) in 556.[10]

|

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was written perhaps about 880AD, several centuries after the events it purports to describe and after Bede's Ecclesiastical History. |

|

Tribal Kingdoms in Wessex Area Hwicce = based on Gloucestershire (later Mercian) Gewisse = based on Upper Thames area Dobunni = Iron Age tribe in Roman period Angles = incomers across North Sea |

But their control wasn’t complete and battles continued. In 577 the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reads Here Cuthwine and Ceawlin (Saxon leaders) fought against the Britons, and they killed three kings, Coinmail and Condidan and Farinmail, in the place which is called Deorham (Dyrham), and took three cities: Gloucester and Cirencester and Bath. The names of the three kings killed at Dyrham are recognisably British and the cities captured are all Romano-British towns with perhaps some degree of administrative continuity. Although we need to be wary of accepting the early Chronicle record as historically accurate, the entry is not entirely implausible.[11]

|

The Chronicle tells us that these locations subsequently fell back under the lordship of the Hwicce rather than the Saxon Gewisse. The Hwicce seem to have occupied a similar area to that of the Dobunni in the Roman period, including Bath and north-west Wiltshire, which may indicate that they remained substantially British.[12] After the Battle of Cirencester in 628, our general area was gradually absorbed into a territory known as Mercia and its Germanic invaders called Angles.[13] However, the battles in Bath and Gloucestershire make it clear that the Saxons had no stronghold in these locations as late as the early 600s, contradicting the proposition of continuous Saxon advances.

Reconciling the Evidence

The Victorian narrative of this period was of Anglo-Saxon hordes sweeping through England and wiping out or enslaving a few surviving sub-Roman Britons cowering amongst the smoking ruins of villas and towns.[14] This is largely based on the writings of the contemporary monk Gildas who asserted that the Britons were either killed or enslaved if they did not flee overseas or to Wales and Cornwall. But this simply doesn’t fit the evidence we have from other sources of objects found, grave bodies or DNA or isotope analysis. The Saxon goods that have been found show great continuity associated with Romano-British lifestyles, suggesting a more gradual change in culture.

The Victorian narrative of this period was of Anglo-Saxon hordes sweeping through England and wiping out or enslaving a few surviving sub-Roman Britons cowering amongst the smoking ruins of villas and towns.[14] This is largely based on the writings of the contemporary monk Gildas who asserted that the Britons were either killed or enslaved if they did not flee overseas or to Wales and Cornwall. But this simply doesn’t fit the evidence we have from other sources of objects found, grave bodies or DNA or isotope analysis. The Saxon goods that have been found show great continuity associated with Romano-British lifestyles, suggesting a more gradual change in culture.

|

The idea that the Saxons drove all opposition westwards into Wales and Cornwall has now been superseded. Rather, the evidence suggests that the native population absorbed incomers and integrated them into a merged culture and society. DNA results seemed to promise much information about this but have been rather inconclusive, showing little change between the people living in Saxon and Welsh areas. For England, the evidence points to the similarity of the DNA of the Caucasian population with about 20%-40% attributable to Germanic origins and at least 60% attributable to earlier indigenous settlers.[15]

|

Traditional Narrative Now that the Romans were gone .. (the Saxons) took up their abode here for ever, slaying the chiefs and warriors of the "Welsh" (as they called the Britons), or driving them before them into the west. F York Powell, History of England to 1509, 1886, p.11 |

There is no evidence in the period 400-600 of a significant number of skeletons with injuries caused by sharp-edge weapons consistent with war massacres.[16] The evidence which does survive shows Saxon grubenhäuser (sunken-featured buildings) usually occurring amongst post-built structures in settlements of rural, farming people. Instead of an invasion and conquest picture of events, a new analysis has been proposed. This suggests a breakdown in civilian government and law and order without the support of the army in the 400s. As localised civil unrest increased, warfare became endemic. In this situation social and political identities changed, leading to the emergence of local states ruled by tribal chiefs. It was not therefore invasion that altered life in the west so much as cultural change and the rise of new elites keen to affirm status and authority in a power vacuum.[17]

|

Bede the Venerable The monk Bede was a teacher, theologian and author who wrote Ecclesiastical History of the English People in Latin from Jarrow, completed about 731. |

Regiones

The chronicler Bede makes some interesting comments about the Gewisse in the mid-600s. He talks about administrative structures below that of the king which he called regiones (regions). Some historians refer to the area south of Wansdyke in terms of regiones.[18] In charge of the regions there appear to have been extended family groups, perhaps levying financial tributes, which some historians have identified as place-names ending in ‘-ingas’ which denotes a family group |

Thus Spalding, Lincolnshire, denotes a place under control of the kinship group of Spalda. There is one possible ingas form in Box at Inghall, marked in Francis Allen’s 1626 map as Ingols and in the 1630 map as Ingolles and Greate Ingolles. However, this is highly unlikely to be a Saxon place-name as the ‘-ingas’ element usually occurs as a suffix, not the first element of a place-name. It is rare that names survive unamended and often the name of the last owner supersedes earlier names, so it is difficult to establish continuity over thousands of years and we need to take care with place-name and fieldname evidence.

We need to be careful about the emotive words used by our sources. The monk Gildas refers to rivers of blood, mass enslavements and destruction of (British) settlements but we shouldn't take the words at face value.[19] For example, we translate the Saxon words fyrd and beadu as army and battle. In modern warfare these words have become decisive military engagements but that does not appear the case in Saxon times when the word fyrd related to either a tribal or shire-based militia or a group of royal household warriors. A later Anglo-Saxon Law Code referred to an army (here) meaning a gathering of men numbering thirty-five people or more, which would make battle victories more like skirmishes. The Code defined up to seven men as thieves, seven to thirty-five as a band, over thirty-five an army.[20] An entire army in 786 comprised only 84 men.[21] We also need to be careful with the whole concept of disputes over land. They were less concerned with taking possession by killing or expelling earlier settlers than to take tribute from them and, in return for the payment, to offer the existing inhabitants protection from others. Tribute was often slaves or hostages which could be returned for a cash payment.

We need to be careful about the emotive words used by our sources. The monk Gildas refers to rivers of blood, mass enslavements and destruction of (British) settlements but we shouldn't take the words at face value.[19] For example, we translate the Saxon words fyrd and beadu as army and battle. In modern warfare these words have become decisive military engagements but that does not appear the case in Saxon times when the word fyrd related to either a tribal or shire-based militia or a group of royal household warriors. A later Anglo-Saxon Law Code referred to an army (here) meaning a gathering of men numbering thirty-five people or more, which would make battle victories more like skirmishes. The Code defined up to seven men as thieves, seven to thirty-five as a band, over thirty-five an army.[20] An entire army in 786 comprised only 84 men.[21] We also need to be careful with the whole concept of disputes over land. They were less concerned with taking possession by killing or expelling earlier settlers than to take tribute from them and, in return for the payment, to offer the existing inhabitants protection from others. Tribute was often slaves or hostages which could be returned for a cash payment.

Conclusion

We need to re-think our narrative of Britain at the close of the Roman era. Undoubtedly there was conflict and violence throughout and beyond much of this period. Grave goods indicate the value evidently placed on fighting prowess. But we should not take all the historical accounts of battles at face value. They are as much about the creation of foundation myths as factual veracity. Some archaeologists claim that some place-names were applied to places associated with conflict to support invented mythologies. Some battles, and the names of their protagonists, were invented to explain pre-existing place-names.[22] The accounts of the early post-Roman records are deeply loaded with symbolism and, where genealogical claims may have been relatively weak, they could be bolstered with the creation of a legitimating back-story.

We need to re-think our narrative of Britain at the close of the Roman era. Undoubtedly there was conflict and violence throughout and beyond much of this period. Grave goods indicate the value evidently placed on fighting prowess. But we should not take all the historical accounts of battles at face value. They are as much about the creation of foundation myths as factual veracity. Some archaeologists claim that some place-names were applied to places associated with conflict to support invented mythologies. Some battles, and the names of their protagonists, were invented to explain pre-existing place-names.[22] The accounts of the early post-Roman records are deeply loaded with symbolism and, where genealogical claims may have been relatively weak, they could be bolstered with the creation of a legitimating back-story.

References

[1] Finds are still being made at regular intervals - see Stunning Dark Ages mosaic found at Roman villa in Cotswolds reported at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/dec/10/stunning-dark-ages-mosaic-found-at-roman-villa-in-cotswolds?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

[2] Emily La Trobe-Bateman and Rosalind Niblett, Bath: An Archaeological Assessment: A Study of Settlement around the Sacred Hot Springs, 2016, Aris & Phillips Ltd, p.108 and 121

[3] Emily La Trobe-Bateman and Rosalind Niblett, Bath: An Archaeological Assessment, p.108

[4] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.34

[5] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.10

[6] Gildas, De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain)

[7] Emily La Trobe-Bateman and Rosalind Niblett, Bath: An Archaeological Assessment, p.111

[8] A recent project undertaken by Professor Steven Rippon and colleagues (S Rippon C Smart and B Pears, (2015) The Fields of Britannia, 2015, shows that there were many places where continuity can be demonstrated in the early medieval period, including in Wiltshire, where there was continuity in the overall orientation of fieldscapes between the Romano-British and later medieval periods. See also Simon Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006. Archaeopress, pp.93-4 and fig.38

[9] Bruce Eagles, “Anglo-Saxon Presence and Culture in Wiltshire, AD 450-c675”, in Roman Wiltshire and After: papers in honour of Ken Annable (editor Peter Ellis), 2001, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, p.200

[10] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.57-9

[11] A Cynddylan is named in a Welsh source as a ruler of the area around Wroxeter, slain by the English in the mid-7th century (P. Sims-Williams 1983, The settlement of England in Bede and the ‘Chronicle’, Anglo-Saxon England, 12, p.1-41)

[12] R Coates, 2013, The name of the Hwicce: a discussion, Anglo-Saxon England, 42, p.51-61

[13] It is obviously the unification of the Angles and the West Saxons which gave us the name Anglo-Saxons. This term was first used in 8th century on the continent, to distinguish English from Continental Saxons; and not used in England until reign of Athelstan in the10th century.

[14] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.60

[15] There are numerous reports on Professor Peter Donnelly’s findings on the internet - https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-31905764

[16] Alice Roberts, King Arthur’s Britain, BBC television, 2018

[17] For an indication of the large number of Anglo-Saxon style burials in the area see Bruce Eagles, From Roman Civitas to Anglo-Saxon Shire, 2018, Oxbow Books, p.102-111

[18] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.39

[19] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.48

[20] Law Code of King Ine (AD 670 - 726) quoted in Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.151

[21] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.67

[22] Thomas Williams, The place of slaughter: exploring the West Saxon battlescape, in R Lavelle and S Roffey Danes in Wessex: the Scandinavian impact on Southern England, c.800 – c.1100, 2016, Oxbow Books, pp.35-55

[1] Finds are still being made at regular intervals - see Stunning Dark Ages mosaic found at Roman villa in Cotswolds reported at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/dec/10/stunning-dark-ages-mosaic-found-at-roman-villa-in-cotswolds?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

[2] Emily La Trobe-Bateman and Rosalind Niblett, Bath: An Archaeological Assessment: A Study of Settlement around the Sacred Hot Springs, 2016, Aris & Phillips Ltd, p.108 and 121

[3] Emily La Trobe-Bateman and Rosalind Niblett, Bath: An Archaeological Assessment, p.108

[4] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.34

[5] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.10

[6] Gildas, De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain)

[7] Emily La Trobe-Bateman and Rosalind Niblett, Bath: An Archaeological Assessment, p.111

[8] A recent project undertaken by Professor Steven Rippon and colleagues (S Rippon C Smart and B Pears, (2015) The Fields of Britannia, 2015, shows that there were many places where continuity can be demonstrated in the early medieval period, including in Wiltshire, where there was continuity in the overall orientation of fieldscapes between the Romano-British and later medieval periods. See also Simon Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006. Archaeopress, pp.93-4 and fig.38

[9] Bruce Eagles, “Anglo-Saxon Presence and Culture in Wiltshire, AD 450-c675”, in Roman Wiltshire and After: papers in honour of Ken Annable (editor Peter Ellis), 2001, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, p.200

[10] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.57-9

[11] A Cynddylan is named in a Welsh source as a ruler of the area around Wroxeter, slain by the English in the mid-7th century (P. Sims-Williams 1983, The settlement of England in Bede and the ‘Chronicle’, Anglo-Saxon England, 12, p.1-41)

[12] R Coates, 2013, The name of the Hwicce: a discussion, Anglo-Saxon England, 42, p.51-61

[13] It is obviously the unification of the Angles and the West Saxons which gave us the name Anglo-Saxons. This term was first used in 8th century on the continent, to distinguish English from Continental Saxons; and not used in England until reign of Athelstan in the10th century.

[14] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.60

[15] There are numerous reports on Professor Peter Donnelly’s findings on the internet - https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-31905764

[16] Alice Roberts, King Arthur’s Britain, BBC television, 2018

[17] For an indication of the large number of Anglo-Saxon style burials in the area see Bruce Eagles, From Roman Civitas to Anglo-Saxon Shire, 2018, Oxbow Books, p.102-111

[18] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.39

[19] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.48

[20] Law Code of King Ine (AD 670 - 726) quoted in Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.151

[21] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.67

[22] Thomas Williams, The place of slaughter: exploring the West Saxon battlescape, in R Lavelle and S Roffey Danes in Wessex: the Scandinavian impact on Southern England, c.800 – c.1100, 2016, Oxbow Books, pp.35-55