Medieval Box Vill Alan Payne September 2024

We all think we know what a village is but it is difficult to define: A clustered human settlement or community larger than a hamlet and smaller than a town .. often located in rural areas.[1] It is easier to list what villages aren’t – not an extended farmstead, nor a cluster of farms, nor a territory based on church or manorial organisation. A village often has a central heart, such as a crossroad, or a road frontage or a village green. It also needs a desire for communal self-identification: where we feel we belong.

Origins of the Vill

The concept of a vill (village) developed in the Anglo-Saxon period as a unit of land smaller than a hundred, entirely separate from the lords' manorial areas (based on land ownership) and the parish area (based on church tithes). The villata (translated as vill or village) was an area of administration covering the people resident in an area centre and scattered farmsteads in surrounding hamlets, which developed when the manor declined. The original purpose of the village was to keeping the peace through the local constable, implementing communal agricultural policy, and contributing militia soldiers to the county's and the country's war needs. militia and

The vill was run by local worthies: wealthy virgate holders, the reeve, jurors, churchwardens, and the constable. As the lord's influence through the manorial court waned, these people took up responsibility for regulating local fields and agricultural co-ordination.[3] By enforcing strict morality and conformity, the officials of the vill brought order to the administration of the local area.[4] After 1334 it was responsible for assessing and collecting local taxes.[2] The vill regulated the quality of ale and bread, woodland usage, crop rotation and roaming livestock. Control by elders was necessary because landholdings and communal grazing rights had become complex by inheritance and the vagueness of local customs.

There is no such thing as the start of Box village because it evolved naturally rather than by creation. Nor were the village boundaries static. When properties became uninhabitable, houses were built on other sites expanding the village and sometimes even whole villages shifted location. We still see this at Ashley where the cluster of properties around Ashley Manor in the Allen maps has now been replaced by roadside development. Spencer’s Farmhouse appears to be very old but it is possible that The Barton, set a right-angle to Ashley Lane, has earlier origins. Often house plots reveal much older sites and have remained more static than the actual buildings. We see this at The Old Jockey where the S-bend in the medieval ridgeway probably underlies earlier houses in this location.

Development of Box Vill as a Community

There are no documetary references to the vill in Box. is conflicting evidence about a settlement in the Box valley at the time of Domesday. Indeed, the word Box does not appear in the Domesday Book and first use of the name as Bocza is in 1144. But there are Domesday references to 5 villani (unfree peasants) in the main Hazelbury text and 2 at Ditteridge. It is likely that some of these people lived in properties grouped around the water mills which existed on the Box Brook. References to quarrying in the early Norman period also indicate collective initiatives at settlements grouped around the quarry areas. But there is no indication of a community nor of local, village administration in the feudal period.

After 1348 lay lords were not resident in Box for generations. It would be feasible to suggest that the communal Box vill extended its authority at that time. Communal decisions were constantly needed about crops, inheritance of commonland rights, and the settlement of disputes. It is probable that the community needed to act together taking the role of the lord’s agent (previously a leading tenant) and the manorial court (thereafter made of notable villeins). By the time of the Allen maps, control had shifted to these authorities from the lord of the manor, who himself had moved out of central Box to Hazelbury Manor.

MORE several fields with strip lynches carved out of enclosed land. The lynches are just visible on the left of the map of Ashley and the red dots seem to imply communal grazing land. But Ashley had no church, no consecrated burial ground and no history of a general administration, other than the lord's manorial court.

The concept of a vill (village) developed in the Anglo-Saxon period as a unit of land smaller than a hundred, entirely separate from the lords' manorial areas (based on land ownership) and the parish area (based on church tithes). The villata (translated as vill or village) was an area of administration covering the people resident in an area centre and scattered farmsteads in surrounding hamlets, which developed when the manor declined. The original purpose of the village was to keeping the peace through the local constable, implementing communal agricultural policy, and contributing militia soldiers to the county's and the country's war needs. militia and

The vill was run by local worthies: wealthy virgate holders, the reeve, jurors, churchwardens, and the constable. As the lord's influence through the manorial court waned, these people took up responsibility for regulating local fields and agricultural co-ordination.[3] By enforcing strict morality and conformity, the officials of the vill brought order to the administration of the local area.[4] After 1334 it was responsible for assessing and collecting local taxes.[2] The vill regulated the quality of ale and bread, woodland usage, crop rotation and roaming livestock. Control by elders was necessary because landholdings and communal grazing rights had become complex by inheritance and the vagueness of local customs.

There is no such thing as the start of Box village because it evolved naturally rather than by creation. Nor were the village boundaries static. When properties became uninhabitable, houses were built on other sites expanding the village and sometimes even whole villages shifted location. We still see this at Ashley where the cluster of properties around Ashley Manor in the Allen maps has now been replaced by roadside development. Spencer’s Farmhouse appears to be very old but it is possible that The Barton, set a right-angle to Ashley Lane, has earlier origins. Often house plots reveal much older sites and have remained more static than the actual buildings. We see this at The Old Jockey where the S-bend in the medieval ridgeway probably underlies earlier houses in this location.

Development of Box Vill as a Community

There are no documetary references to the vill in Box. is conflicting evidence about a settlement in the Box valley at the time of Domesday. Indeed, the word Box does not appear in the Domesday Book and first use of the name as Bocza is in 1144. But there are Domesday references to 5 villani (unfree peasants) in the main Hazelbury text and 2 at Ditteridge. It is likely that some of these people lived in properties grouped around the water mills which existed on the Box Brook. References to quarrying in the early Norman period also indicate collective initiatives at settlements grouped around the quarry areas. But there is no indication of a community nor of local, village administration in the feudal period.

After 1348 lay lords were not resident in Box for generations. It would be feasible to suggest that the communal Box vill extended its authority at that time. Communal decisions were constantly needed about crops, inheritance of commonland rights, and the settlement of disputes. It is probable that the community needed to act together taking the role of the lord’s agent (previously a leading tenant) and the manorial court (thereafter made of notable villeins). By the time of the Allen maps, control had shifted to these authorities from the lord of the manor, who himself had moved out of central Box to Hazelbury Manor.

MORE several fields with strip lynches carved out of enclosed land. The lynches are just visible on the left of the map of Ashley and the red dots seem to imply communal grazing land. But Ashley had no church, no consecrated burial ground and no history of a general administration, other than the lord's manorial court.

Location of the Court of the Vill

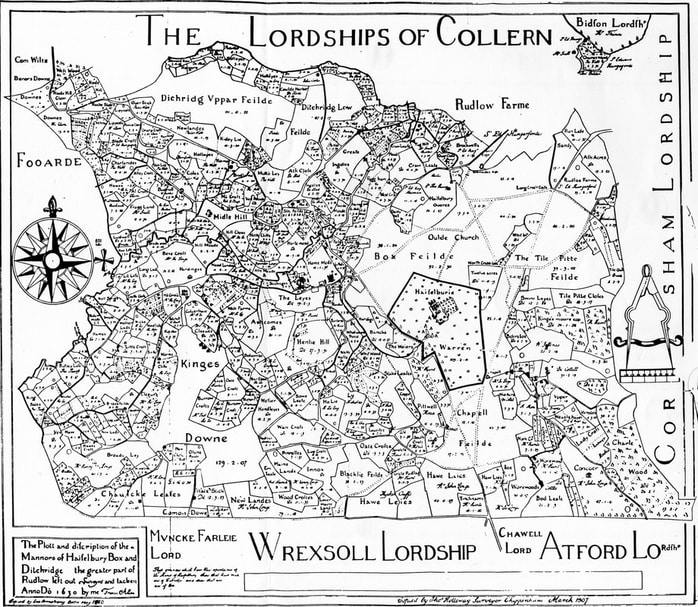

There is no obvious location for the holding of the village court, although it is likely that a site would have been in central Box. The Allen maps of 1626 and 1630 show how few properties existed in the centre. Some large properties were isolated farmsteads in the hamlets, unlikely to be suitable as a regular court. The significant central residences were around Box Church, in the Market Place, and (to a lesser extent) at Ashley. Outside some residential areas were woodlands needed for timber and grazing of pigs and there was little development to the east and south of the present Box Post Office because this area was all part of the communally-owned Box Field.

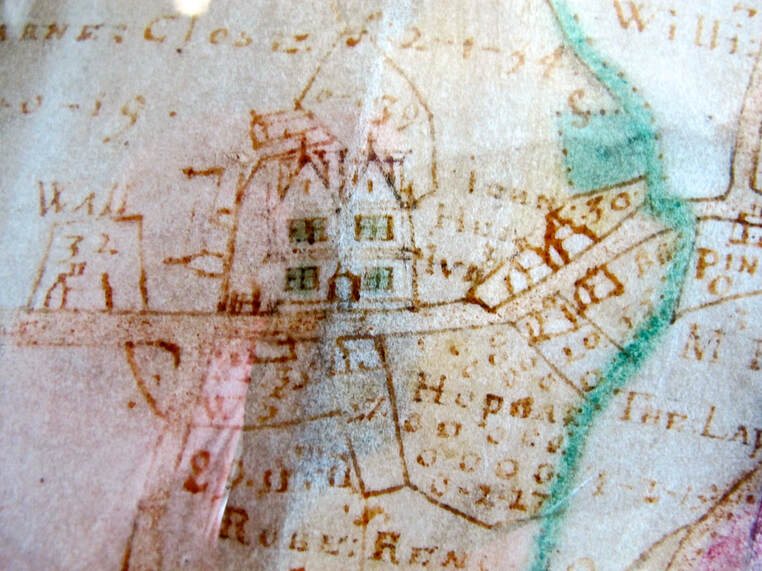

Potential court sites in central Box are limited. The Allen maps show an unusual building to the west of the Manor House which appears to be described as WALL. It is possible that this was later the site of the Queens Head, and that the premises served as a community venue as did The Bear in the seventeenth and subsequent centuries. Having said that, the description of the site could mean that it was the village lockup for animals (the Pound) or possibly The Blind House. The Manor House shown on the maps was redeveloped by the Speke family in the early 1600s and the late medieval appearance of this area has been obliterated. Properties on both sides of the Market Place look suspiciously like shops.

There is no obvious location for the holding of the village court, although it is likely that a site would have been in central Box. The Allen maps of 1626 and 1630 show how few properties existed in the centre. Some large properties were isolated farmsteads in the hamlets, unlikely to be suitable as a regular court. The significant central residences were around Box Church, in the Market Place, and (to a lesser extent) at Ashley. Outside some residential areas were woodlands needed for timber and grazing of pigs and there was little development to the east and south of the present Box Post Office because this area was all part of the communally-owned Box Field.

Potential court sites in central Box are limited. The Allen maps show an unusual building to the west of the Manor House which appears to be described as WALL. It is possible that this was later the site of the Queens Head, and that the premises served as a community venue as did The Bear in the seventeenth and subsequent centuries. Having said that, the description of the site could mean that it was the village lockup for animals (the Pound) or possibly The Blind House. The Manor House shown on the maps was redeveloped by the Speke family in the early 1600s and the late medieval appearance of this area has been obliterated. Properties on both sides of the Market Place look suspiciously like shops.

We can also see how restricted residential housing was in central Box from the field names surrounding those areas: to the east Box Fields, to the south The Leys, westwards Stickings (Stichnges) and Ash Mead, and in the north Home Farm and Horsemead. The houses themselves were sited away from the By Brook clear of the floodplain and the roads developed to service the houses. We can see the wetland areas in the fieldnames Stichnges, Fogham (marshy, water meadows).

Another possible building was Box Church itself, the only communal property in central Box, The area around Box Church on the Allen maps clearly shows the importance of this area with a grand church edifice and fields marked as owned by the vicar and a separate field and house owned by the parson to the east of the church. In upper rooms of the north aisle was the Church Ecclesiastical Court (now demolished). The responsibilities of the Church Court included marriage, wills, inheritances and, more than these aspects, the moral responsibility for individual misbehaviour and communal information. There are several buildings in this area, many apparently houses but not surrounded by their own land and possibly specialist artisan cottages. Both the importance of common worship and existence of non-farming service areas also centralised this area for those living in the hamlets.

It is also possible that the location of the vill court was not a dedicated building. It could have been held in different private houses and that these changed as the principal tenant altered.

It is also possible that the location of the vill court was not a dedicated building. It could have been held in different private houses and that these changed as the principal tenant altered.

The properties in the hamlets are clearly different to the central areas with individual cottages set in their own grounds and

The road system also focussed the centre of Box as an administrative location. The area around the Manor House was central to the east-west route from the Box Common Fields to Ashley Lane and approximately at the crossroads of the north-south road we call Mill Lane and going up to Ditteridge and the Fosse Way and south to Chapel Plaister and the medieval ridgeway road. Several tracks lead from Kingsdown to the central village for this purpose. These routes offered access to markets in local towns and animal markets vital for the survival of medieval villages.

We do not know if there was a specific building in which the village authorities met, if they used local houses, the church or even the manorial court. However, there is a reference in the 1840 Tithe Apportionment map (marked in red) to 187c (next to Miller’s on the High Street) was called Parish Pound owned by Box Parish Authorities. Could the village meeting place be around this area?

The road system also focussed the centre of Box as an administrative location. The area around the Manor House was central to the east-west route from the Box Common Fields to Ashley Lane and approximately at the crossroads of the north-south road we call Mill Lane and going up to Ditteridge and the Fosse Way and south to Chapel Plaister and the medieval ridgeway road. Several tracks lead from Kingsdown to the central village for this purpose. These routes offered access to markets in local towns and animal markets vital for the survival of medieval villages.

We do not know if there was a specific building in which the village authorities met, if they used local houses, the church or even the manorial court. However, there is a reference in the 1840 Tithe Apportionment map (marked in red) to 187c (next to Miller’s on the High Street) was called Parish Pound owned by Box Parish Authorities. Could the village meeting place be around this area?

References

[1] Wikipedia, Village - Wikipedia

[2] Christopher Dyer, Everyday Life in Medieval England, 1994, p.4

[3] Christopher Dyer, Everyday Life in Medieval England, 1994, Hambledon Press, p.7

[4] John Hatcher, The Black Death, 2008, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p.2-6

[1] Wikipedia, Village - Wikipedia

[2] Christopher Dyer, Everyday Life in Medieval England, 1994, p.4

[3] Christopher Dyer, Everyday Life in Medieval England, 1994, Hambledon Press, p.7

[4] John Hatcher, The Black Death, 2008, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p.2-6