|

Dangers at Box Mill

Alan Payne Photographs Jane Browning December 2018 Jane Browning wrote to us: I thought readers might be interested in this photo of Box Mill taken in 1916 of the weir crossing behind Box Mill (later known as Spafax, now Peter Gabriel's studio). This weir was known as The Hatches and the path did cross then. When I was small, I used to walk across quite tentatively - especially if the brook was in spate. it was just spaced wooden planks and the noise could be quite something! Peter Gabriel had the route of the footpath changed to what it is now. |

Death by Water

Fatalities in Box Brook were a common occurrence until recent times. One of the strangest was a suicide in 1905 of Rose Matthews, aged 31 of Colerne, who cast off her hat and jumped into the water at the back of Box Mill.[1] The speed of the water carried her body down to The Wharf where it was retrieved. The inquest found Suicide during temporary insanity.

Swimming in Box Brook caused frequent mishaps and often tragedies. There are numerous local reports of incidents such as the death of nine-year-old Willie Pinson of Box Hill in 1919 between Box Mill and Drewett’s Mill .. bathing in shallow water when they ventured into a deeper part.[2] He drowned in one of the deeper holes that abound in the bed of the brook.

The speed of the water and its depth at The Hatches was a constant source of danger to young children. In 1849 a report of eight-year-old James Hancock told how, on a visit from Bath to his relatives at Box Mill, he fell into the backwater below the hatches and minutes later was pulled out dead.[3]

The Fire Sermon

As well as issues of water danger, the amount of machinery and the inflammable nature of floors, lifts and stacking equipment were frequent fire hazards. The whole building was in peril in 1899 when a fire broke out at Box Railway Station.[4] Thirteen barrels of naptha belonging to GWR exploded in a store in a corrugated iron house at the Box Tunnel end. The material was used for filling the lamps of night watchmen and caused the whole of the naptha to ignite. A night watchman cut the emergency wire in the Tunnel stopping trains going through about midnight as the burning liquid ran down onto the rails. The liquid ran into Box Brook and the mill was in danger until Mr James Browning diverted the water course into a backwater. A field of barley was in danger of going up in flames but a large crowd of villagers, PC Mead and the Box Fire Brigade kept the flames in check until they burned themselves out. By 4.30am the fire was extinguished and the railway lines reopened.

Fatalities in Box Brook were a common occurrence until recent times. One of the strangest was a suicide in 1905 of Rose Matthews, aged 31 of Colerne, who cast off her hat and jumped into the water at the back of Box Mill.[1] The speed of the water carried her body down to The Wharf where it was retrieved. The inquest found Suicide during temporary insanity.

Swimming in Box Brook caused frequent mishaps and often tragedies. There are numerous local reports of incidents such as the death of nine-year-old Willie Pinson of Box Hill in 1919 between Box Mill and Drewett’s Mill .. bathing in shallow water when they ventured into a deeper part.[2] He drowned in one of the deeper holes that abound in the bed of the brook.

The speed of the water and its depth at The Hatches was a constant source of danger to young children. In 1849 a report of eight-year-old James Hancock told how, on a visit from Bath to his relatives at Box Mill, he fell into the backwater below the hatches and minutes later was pulled out dead.[3]

The Fire Sermon

As well as issues of water danger, the amount of machinery and the inflammable nature of floors, lifts and stacking equipment were frequent fire hazards. The whole building was in peril in 1899 when a fire broke out at Box Railway Station.[4] Thirteen barrels of naptha belonging to GWR exploded in a store in a corrugated iron house at the Box Tunnel end. The material was used for filling the lamps of night watchmen and caused the whole of the naptha to ignite. A night watchman cut the emergency wire in the Tunnel stopping trains going through about midnight as the burning liquid ran down onto the rails. The liquid ran into Box Brook and the mill was in danger until Mr James Browning diverted the water course into a backwater. A field of barley was in danger of going up in flames but a large crowd of villagers, PC Mead and the Box Fire Brigade kept the flames in check until they burned themselves out. By 4.30am the fire was extinguished and the railway lines reopened.

Above left: Duck pond on Box Brook, 1916. Above right: Weir at Drewett’s Mill

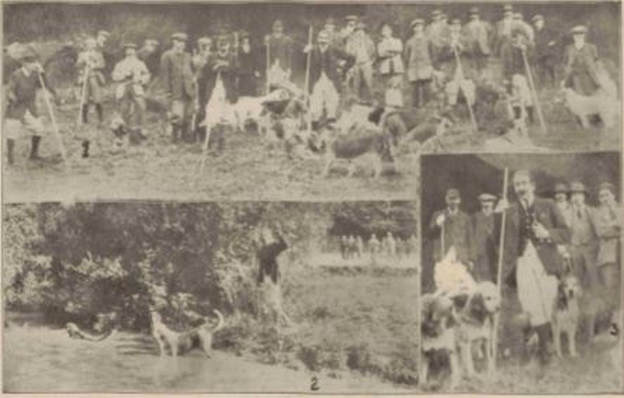

A Game of Chess: Otter Hunts

Notwithstanding the danger of the waterway, the Box Brook was a sporting place for otter hunts in the early 1900s. The hounds of Courtney Tracy of Wilton, Salisbury, came to Box in 1908 with the members of the hunt easily distinguished by their special costume, footwear, and the spiked poles they carried.[5] They drew a big crowd from four to five hundred people. There were awkward stiles and ditches around Box Mill to be negotiated and the report goes on to say that no fun was encountered at Box Mill and the party went on to Drewett’s Mill, despite the fact that the sun beat down fiercely and soon took the starch out of the collar. No otters were found in the Box area and the twenty-six hounds in the pack chased a fox which had been disturbed at Colerne Park. Eventually two otters were found at Castle Combe, a female and her cub, which proved a rather easy victim to the hounds as after only ten minutes chase it was killed.

The hunt was a regular event in the years before the First World War. In 1910 the hunt started from Shockerwick Bridge.[6] Again, at Castle Combe an otter was scented and a kill made, and the pads were distributed, according to the customs of the hunt. A similar hunt followed in 1913 on a glorious September day, brilliant sunshine and a countryside fresh and sparkling after heavy rain.[7] The hounds caught several scents but no otters. The author of the newspaper article used allusions to A Midsummer Night’s Dream and flowery language (through some delightful pastural and sylvan scenery ) but acknowledged that some wanted otter-hunting to be banned like badgering and bear-baiting.

Notwithstanding the danger of the waterway, the Box Brook was a sporting place for otter hunts in the early 1900s. The hounds of Courtney Tracy of Wilton, Salisbury, came to Box in 1908 with the members of the hunt easily distinguished by their special costume, footwear, and the spiked poles they carried.[5] They drew a big crowd from four to five hundred people. There were awkward stiles and ditches around Box Mill to be negotiated and the report goes on to say that no fun was encountered at Box Mill and the party went on to Drewett’s Mill, despite the fact that the sun beat down fiercely and soon took the starch out of the collar. No otters were found in the Box area and the twenty-six hounds in the pack chased a fox which had been disturbed at Colerne Park. Eventually two otters were found at Castle Combe, a female and her cub, which proved a rather easy victim to the hounds as after only ten minutes chase it was killed.

The hunt was a regular event in the years before the First World War. In 1910 the hunt started from Shockerwick Bridge.[6] Again, at Castle Combe an otter was scented and a kill made, and the pads were distributed, according to the customs of the hunt. A similar hunt followed in 1913 on a glorious September day, brilliant sunshine and a countryside fresh and sparkling after heavy rain.[7] The hounds caught several scents but no otters. The author of the newspaper article used allusions to A Midsummer Night’s Dream and flowery language (through some delightful pastural and sylvan scenery ) but acknowledged that some wanted otter-hunting to be banned like badgering and bear-baiting.

As if any verification were needed, Jane Browning produced a couple of original photographs of the Otter Hunt in 1912.

The quality isn't brilliant but they are unique in the history of Box - unless anyone can prove me wrong by finding other photographs? I would be delighted to be corrected.

The quality isn't brilliant but they are unique in the history of Box - unless anyone can prove me wrong by finding other photographs? I would be delighted to be corrected.

Conclusion

We forget how important and scarce water was in previous years because water is so readily available from domestic taps in our homes. It was a breeding ground for wildlife, vital for irrigation in dry summers and important to drive machinery before steam power became common. Its use and abuse were contested by those wishing to use the Box Brook. In 1837 the owners of the mills from Cold Ashton to Bathford wrote an open warning in the local newspaper to persons diverting the watercourse of the brook for watering lands (or otherwise).[8] The Box owners included William Pinchin and JL Phillips at Box Mill, Thomas Browning at Drewett’s Mill and William James at Cutting Mill. With the opening of Box Tunnels, coal became more readily available in the village and now the Brook has lost much of its significance.

We forget how important and scarce water was in previous years because water is so readily available from domestic taps in our homes. It was a breeding ground for wildlife, vital for irrigation in dry summers and important to drive machinery before steam power became common. Its use and abuse were contested by those wishing to use the Box Brook. In 1837 the owners of the mills from Cold Ashton to Bathford wrote an open warning in the local newspaper to persons diverting the watercourse of the brook for watering lands (or otherwise).[8] The Box owners included William Pinchin and JL Phillips at Box Mill, Thomas Browning at Drewett’s Mill and William James at Cutting Mill. With the opening of Box Tunnels, coal became more readily available in the village and now the Brook has lost much of its significance.

References

[1] The Bath Chronicle, 14 December 1905

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 14 June 1919

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 17 May 1849

[4] The Wiltshire Times, 5 August 1899

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 27 August 1908

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 18 August 1910

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 13 September 1913

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 24 August 1837

[1] The Bath Chronicle, 14 December 1905

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 14 June 1919

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 17 May 1849

[4] The Wiltshire Times, 5 August 1899

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 27 August 1908

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 18 August 1910

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 13 September 1913

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 24 August 1837