|

Box Before the Normans

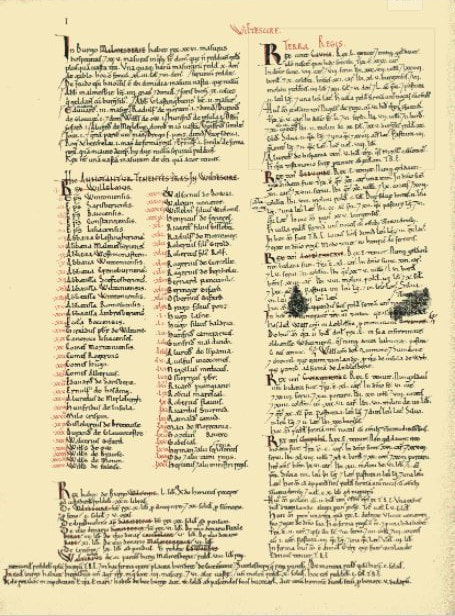

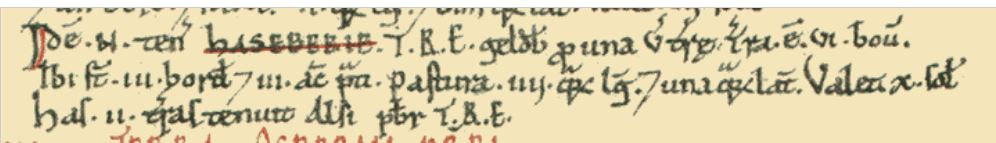

Alan Payne and Jonathan Parkhouse June 2021 The first documentary evidence of Saxon Box comes in the Domesday Book of 1086, twenty years after the Norman invasion, when it refers to areas TRE ("tempore regis Edwardi" meaning "at the time of King Edward the Confessor") in 1066. The reference clearly ignores the claim of King Harold, deemed to be spurious by the Normans. The book is full of abbreviations of medieval Latin which makes it more statistical rather than descriptive. It is also full of words whose nuances are unclear - such as "hida", "caruca", "villanus" and "quarentina" , which we translate as hide, plough, villein and furlong and then speculate about the precise meaning. Before considering the Domesday evidence, it is worthwhile to consider the circumstances that led to the need for William's survey of England before the rule of King Harold Godwine. Left: A page of the Domesday record of Wiltshire (courtesy opendomesday.org |

Godwine Family

Traditionally the Godwine family have been thought of as an English family because they were the most powerful supporter of the new (Cnut’s] dynasty.[1] They were endorsed by the Viking ruler Cnut the Great, king of England 1016-35, who created the family Earls of Wessex. The first Earl married a Danish noblewoman, Gytha Thorkelsdóttir, sister-in-law of Cnut, and the Wessexes had children, Sweyn, Tostig, Harold, Gyrth, Leofwine and Harold, the latter being the man killed at Hastings by William I. They were a very ambitious family and in September 1051, King Edward the Confessor exiled Godwine following a rebellion. A year later Godwine returned from exile, sailed a large fleet into London and forced King Edward to reinstate him.

In April 1053 Godwin died and was succeeded by his son Harold Godwinson as the Earl of Wessex, later Harold I of England.

By 1066, the largest estate in Wiltshire after the king belonged to the Godwine family.[2] Earl Harold held 220 hides, his mother Glytha 100 hides, his sister Queen Edith 87 hides, and his brother Earl Tosti 44 hides, including Corsham. They had amassed considerable land during the disruption half a century beforehand. Wiltshire, Hampshire and Berkshire appear to have been grouped together under the control of ealdorman Aelfric in the period 997 to 1016 and after by Godwin (and his son Harold) in the period 1018 to 1066.[3] The king had an alternative control structure through the role of the shire-reeve, who reported to the crown and exercised control of smaller shire areas, the hundreds, by the middle of the 1000s. One of the reeves’ main roles was to collect rents owed from royal manors which were usually extracted from residents.[4] Shire-reeves weren't paid as such but kept a portion of goods in kind.

Some 14% of the thegns’ manors in Wiltshire in the Domesday Book were owned by people with Danish names. It has been suggested that these were ‘real’ Danes, first or second-generation migrants who had fought with Swein and Cnut during the campaigns of 1013-16. Separate groups were ‘Anglo-Danes’, descendants of those Vikings who had arrived in the 10th century, and ‘adoptive’ Danes, who were English families who took on elements of Danish identity during Cnut’s reign, sometimes through intermarriage, but recognising the cultural orientation of Cnut’s court.[5] Certainly, Godwine bought into the new culture.

Traditionally the Godwine family have been thought of as an English family because they were the most powerful supporter of the new (Cnut’s] dynasty.[1] They were endorsed by the Viking ruler Cnut the Great, king of England 1016-35, who created the family Earls of Wessex. The first Earl married a Danish noblewoman, Gytha Thorkelsdóttir, sister-in-law of Cnut, and the Wessexes had children, Sweyn, Tostig, Harold, Gyrth, Leofwine and Harold, the latter being the man killed at Hastings by William I. They were a very ambitious family and in September 1051, King Edward the Confessor exiled Godwine following a rebellion. A year later Godwine returned from exile, sailed a large fleet into London and forced King Edward to reinstate him.

In April 1053 Godwin died and was succeeded by his son Harold Godwinson as the Earl of Wessex, later Harold I of England.

By 1066, the largest estate in Wiltshire after the king belonged to the Godwine family.[2] Earl Harold held 220 hides, his mother Glytha 100 hides, his sister Queen Edith 87 hides, and his brother Earl Tosti 44 hides, including Corsham. They had amassed considerable land during the disruption half a century beforehand. Wiltshire, Hampshire and Berkshire appear to have been grouped together under the control of ealdorman Aelfric in the period 997 to 1016 and after by Godwin (and his son Harold) in the period 1018 to 1066.[3] The king had an alternative control structure through the role of the shire-reeve, who reported to the crown and exercised control of smaller shire areas, the hundreds, by the middle of the 1000s. One of the reeves’ main roles was to collect rents owed from royal manors which were usually extracted from residents.[4] Shire-reeves weren't paid as such but kept a portion of goods in kind.

Some 14% of the thegns’ manors in Wiltshire in the Domesday Book were owned by people with Danish names. It has been suggested that these were ‘real’ Danes, first or second-generation migrants who had fought with Swein and Cnut during the campaigns of 1013-16. Separate groups were ‘Anglo-Danes’, descendants of those Vikings who had arrived in the 10th century, and ‘adoptive’ Danes, who were English families who took on elements of Danish identity during Cnut’s reign, sometimes through intermarriage, but recognising the cultural orientation of Cnut’s court.[5] Certainly, Godwine bought into the new culture.

|

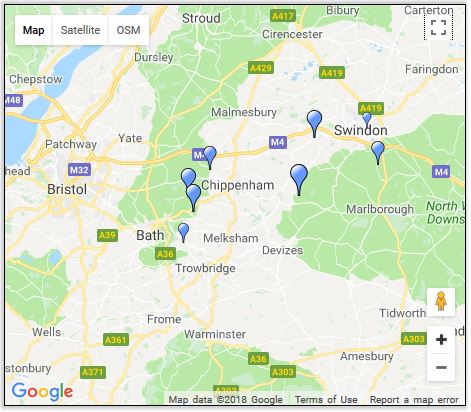

Leofnoth, Local Nobleman Because of Domesday, we know that the owner of much Box land before 1066 was a man called Leofnoth. But we know very little about who he was. Leofnoth was a common name in the late Saxon period, Leof being the Saxon word for friendly and noth meaning strength.[6] There are over a hundred references to this name in the Domesday record and several spellings: Leuenot, Leuenod, and Leueno, all considered by linguists to be the same name but not necessarily the same person.[7] Although we can’t be certain, the closeness of localities might suggest that the Leofnoth or Leuenod named in Colerne and Box were the same person. Map of Leofnoth’s holdings (courtesy https://opendomesday.org/name/332600/leofnoth/ ) |

The Domesday Leofnoth was an important nobleman who held considerable land locally of 40 hides spread over 37 manors.[8] Before 1066, Leofnoth held 5 hides at Hazelbury and 10 hides at Colerne. He thereby controlled both sides of Box Valley, the water mills on the Brook and the meadows that bordered the Brook. This was prime agricultural land arable, meadows and woodland and holding land on both sides of the valley relates to the valley as a prime farming area, needed for resourcing the army. It was a substantial holding bearing in mind that the largest single Wiltshire manor outside of the king's was 30 hides.[9]

Not only did Leofnoth control Box valley but a person of this name was a major player in other North Wiltshire sites.[10] He held 5½ hides at Compton Bassett from King Edward; 4½ at Cumberwell, Bradford-on-Avon from King Edward; 10 at Draycot Foliat (of which 5 hides were in demesne, meaning that he probably resided there); and 3 virgates at Walcot from King Edward.[11]

He also owned property at Yatton Keynell and Wootton Bassett. The references to King Edward may indicate that Leofnoth was a royal official, probably not a thegn but perhaps a manorial reeve, who collected money and food rents from tenants. We might suspect that the Box valley from Hazelbury to Colerne was administered as a single unit by Leofnoth. We know that small local units were centred on a head manor (caput) which offered protection against attack in return for the provision of services and goods and it would seem that Colerne was one of Leofnoth’s main residences, a larger area than Box with about 1,200 acres compared to about 600 acres, and Colerne also had 10 slaves (possibly some domestic workers) living there.[12].

In 1066, we might imagine that Leofnoth’s main duty was to control the fyrd (local militia) and to provision the army from the resources of his landholdings. But the use of partly-trained local militia has sometimes been claimed to be a reason why Harold lost the Battle of Hastings. His war tactics were based on shield-war, with the fyrd sheltering behind a shield wall and making forward rushes with knives and spears. In contrast, the Normans used archers and infantry to soften up the enemy and then the power of the mounted cavalry and armoured knights (almost like modern tanks) to overpower them. This is perhaps a simplistic view as Harold’s forces were made up of select troops from all over England and the Danish housecarls (select personal troops) recruited by Cnut.[13] On the opposite side, the Normans had extended the so-called feudal system (based on land holdings which originally started in early medieval times) specifically to provision their military needs.

There are references in the Domesday Book to the king’s entitlement to the third penny from Bath, Malmesbury and other Wiltshire towns.[14]This is usually interpreted to mean that he was due a third of the fines paid and the rest going to the local lord who administered the court. The significance of this was that the king reduced his usual take of two-thirds of court fines, perhaps indicating the need to further support the aristocracy in these areas.

Not only did Leofnoth control Box valley but a person of this name was a major player in other North Wiltshire sites.[10] He held 5½ hides at Compton Bassett from King Edward; 4½ at Cumberwell, Bradford-on-Avon from King Edward; 10 at Draycot Foliat (of which 5 hides were in demesne, meaning that he probably resided there); and 3 virgates at Walcot from King Edward.[11]

He also owned property at Yatton Keynell and Wootton Bassett. The references to King Edward may indicate that Leofnoth was a royal official, probably not a thegn but perhaps a manorial reeve, who collected money and food rents from tenants. We might suspect that the Box valley from Hazelbury to Colerne was administered as a single unit by Leofnoth. We know that small local units were centred on a head manor (caput) which offered protection against attack in return for the provision of services and goods and it would seem that Colerne was one of Leofnoth’s main residences, a larger area than Box with about 1,200 acres compared to about 600 acres, and Colerne also had 10 slaves (possibly some domestic workers) living there.[12].

In 1066, we might imagine that Leofnoth’s main duty was to control the fyrd (local militia) and to provision the army from the resources of his landholdings. But the use of partly-trained local militia has sometimes been claimed to be a reason why Harold lost the Battle of Hastings. His war tactics were based on shield-war, with the fyrd sheltering behind a shield wall and making forward rushes with knives and spears. In contrast, the Normans used archers and infantry to soften up the enemy and then the power of the mounted cavalry and armoured knights (almost like modern tanks) to overpower them. This is perhaps a simplistic view as Harold’s forces were made up of select troops from all over England and the Danish housecarls (select personal troops) recruited by Cnut.[13] On the opposite side, the Normans had extended the so-called feudal system (based on land holdings which originally started in early medieval times) specifically to provision their military needs.

There are references in the Domesday Book to the king’s entitlement to the third penny from Bath, Malmesbury and other Wiltshire towns.[14]This is usually interpreted to mean that he was due a third of the fines paid and the rest going to the local lord who administered the court. The significance of this was that the king reduced his usual take of two-thirds of court fines, perhaps indicating the need to further support the aristocracy in these areas.

Hazelbury Holding

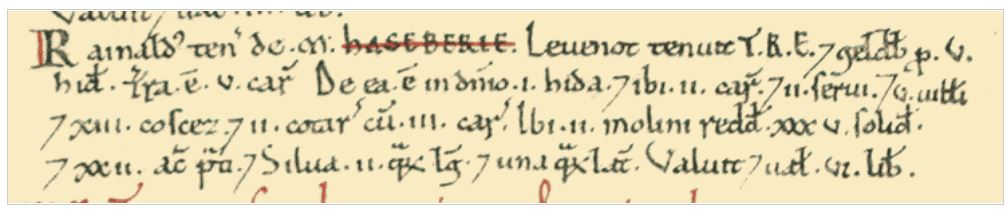

The largest Box land holding in the Domesday Book was at Hazelbury under tenant-in-chief Miles Crispin, held by lord Reginald (Rainald). In 1066 it was described as:

Leofnoth held (Hazelbury) before 1066; it paid tax for 5 hides. Land for 5 ploughs, of which 1 hide is in lordship; 2 ploughs there; 2 slaves; 5 villani, 13 Cottars and 2 cottars with 3 ploughs. 2 mills which pay 35s; meadow, 22 acres; woodland 2 furlongs long and 1 furlong wide. The value was and is £6.

This area was substantial - five hides was perhaps 250 hectares or 600 acres - compared to Biddestone 1 hide and Kington St. Michael 1½ hides. But this is not absolute because hides were not a precise geographic measurement, rather they were an assessment of geld tax that the occupiers of the land were obliged to pay to support the king and military needs.[15] Numerous households were recorded. We might imagine a total adult population of over 80 adults (based on 5 people in lord’s household, 4 in each villani’s household, 3 in cottars and smallholders). We need to take care with our translations of these terms to avoid giving modern overtones - villani refers to small tenant farmers holding perhaps 30 acres (not modern villagers as the word has sometimes been mistranslated).[16] The cottars are tenants with perhaps 5 acres or less, slaves are workers on the lord’s demesne land.[17]

Many historians have taken the word Hazelbury to refer to the area around Hazelbury Manor but this simply doesn’t appear to be correct and the land described appears to be the area we call Box. We can verify this for at least part of the land - the mills - would have been on the By Brook as the only watermills existing at this time. Some of the villeins mentioned may have been the miller, his family and possibly others, such as blacksmith and carpenter. The land for 5 ploughs may be the area described in the 1630 map as Box Fields. This was a large area; a single plough being the amount of land that a team of 8 oxen could plough in a day. The lord’s one hide was part of this open-field area. The 22 acres of meadow may have been The Ley area; the woodland is the woods above them.[18] In addition to this area was wasteland, a valuable economic resource, omitted from the Domesday survey. The area described simply doesn’t coincide with modern Hazelbury.

The largest Box land holding in the Domesday Book was at Hazelbury under tenant-in-chief Miles Crispin, held by lord Reginald (Rainald). In 1066 it was described as:

Leofnoth held (Hazelbury) before 1066; it paid tax for 5 hides. Land for 5 ploughs, of which 1 hide is in lordship; 2 ploughs there; 2 slaves; 5 villani, 13 Cottars and 2 cottars with 3 ploughs. 2 mills which pay 35s; meadow, 22 acres; woodland 2 furlongs long and 1 furlong wide. The value was and is £6.

This area was substantial - five hides was perhaps 250 hectares or 600 acres - compared to Biddestone 1 hide and Kington St. Michael 1½ hides. But this is not absolute because hides were not a precise geographic measurement, rather they were an assessment of geld tax that the occupiers of the land were obliged to pay to support the king and military needs.[15] Numerous households were recorded. We might imagine a total adult population of over 80 adults (based on 5 people in lord’s household, 4 in each villani’s household, 3 in cottars and smallholders). We need to take care with our translations of these terms to avoid giving modern overtones - villani refers to small tenant farmers holding perhaps 30 acres (not modern villagers as the word has sometimes been mistranslated).[16] The cottars are tenants with perhaps 5 acres or less, slaves are workers on the lord’s demesne land.[17]

Many historians have taken the word Hazelbury to refer to the area around Hazelbury Manor but this simply doesn’t appear to be correct and the land described appears to be the area we call Box. We can verify this for at least part of the land - the mills - would have been on the By Brook as the only watermills existing at this time. Some of the villeins mentioned may have been the miller, his family and possibly others, such as blacksmith and carpenter. The land for 5 ploughs may be the area described in the 1630 map as Box Fields. This was a large area; a single plough being the amount of land that a team of 8 oxen could plough in a day. The lord’s one hide was part of this open-field area. The 22 acres of meadow may have been The Ley area; the woodland is the woods above them.[18] In addition to this area was wasteland, a valuable economic resource, omitted from the Domesday survey. The area described simply doesn’t coincide with modern Hazelbury.

Ditteridge Holding

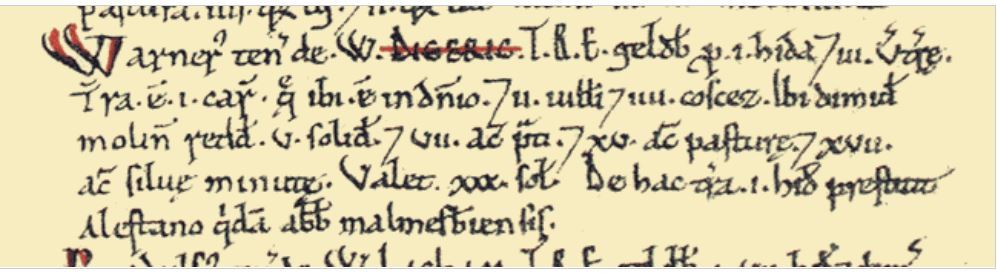

Under the holding of tenant-in-chief William of Eu was Warner of Ditteridge, described as:

Before 1066 (Aelstan held Ditteridge) it paid tax for 1 hide and 3 virgates of land. Land for 1 plough, which is there, in lordship; 2 villani and 4 cottars. Half mill which pays 5s; meadow, 7 acres; pasture, 15 acres; underwood, 17 acres. Value 30s. An Abbot of Malmesbury leased 1 hide of this land to Aelstan.

Aelstan of Boscombe, Bournemouth, was one of the richest Saxon clerical thegns in King Edward's time.[19] He held 230 hides divided over 8 shires, including 80 hides in Wiltshire. It is believed that he came from a wealthy Saxon family who had built up their estates over several generations.[20] His other local holdings included 6 hides at West Lavington and 1 hide at Bremhill and possibly 1 virgate at Yatton Keynell, most of which connected with Malmesbury Abbey or Salisbury Church. Ditteridge manor was not held directly but leased from the Abbot of Malmesbury, an interesting reference perhaps to the strange parochial origins of Ditteridge.

Under the holding of tenant-in-chief William of Eu was Warner of Ditteridge, described as:

Before 1066 (Aelstan held Ditteridge) it paid tax for 1 hide and 3 virgates of land. Land for 1 plough, which is there, in lordship; 2 villani and 4 cottars. Half mill which pays 5s; meadow, 7 acres; pasture, 15 acres; underwood, 17 acres. Value 30s. An Abbot of Malmesbury leased 1 hide of this land to Aelstan.

Aelstan of Boscombe, Bournemouth, was one of the richest Saxon clerical thegns in King Edward's time.[19] He held 230 hides divided over 8 shires, including 80 hides in Wiltshire. It is believed that he came from a wealthy Saxon family who had built up their estates over several generations.[20] His other local holdings included 6 hides at West Lavington and 1 hide at Bremhill and possibly 1 virgate at Yatton Keynell, most of which connected with Malmesbury Abbey or Salisbury Church. Ditteridge manor was not held directly but leased from the Abbot of Malmesbury, an interesting reference perhaps to the strange parochial origins of Ditteridge.

Alfsi Holding

Before 1066 (Alfsi the priest held another holding in Hazelbury) it paid tax for 1 virgate of land (quarter of a hide). Land for 6 oxen. 3 smallholders. Meadow, 3 acres; pasture 4 furlongs long and 1 furlong wide. Value 10s.

Alfsi held three other properties before 1066, none local, none in 1086. Alfsi the priest (an English priest sometimes called Spirtes) held a small area of land.[21] Many holdings in Domesday are small, scattered and disparate. They had evolved over centuries of Saxon development without strict male primogeniture and the granting of deathbed holdings to secure religious salvation.[22] Many holdings were split into numerous, different holdings or held jointly (but not in our area). Spirtes seems to have been a very wealthy person, favourite of King Edward and there has been speculation that he was a member of the Abbey of St Mary of Montebourg, near Cherbourg, France.[23]

Before 1066 (Alfsi the priest held another holding in Hazelbury) it paid tax for 1 virgate of land (quarter of a hide). Land for 6 oxen. 3 smallholders. Meadow, 3 acres; pasture 4 furlongs long and 1 furlong wide. Value 10s.

Alfsi held three other properties before 1066, none local, none in 1086. Alfsi the priest (an English priest sometimes called Spirtes) held a small area of land.[21] Many holdings in Domesday are small, scattered and disparate. They had evolved over centuries of Saxon development without strict male primogeniture and the granting of deathbed holdings to secure religious salvation.[22] Many holdings were split into numerous, different holdings or held jointly (but not in our area). Spirtes seems to have been a very wealthy person, favourite of King Edward and there has been speculation that he was a member of the Abbey of St Mary of Montebourg, near Cherbourg, France.[23]

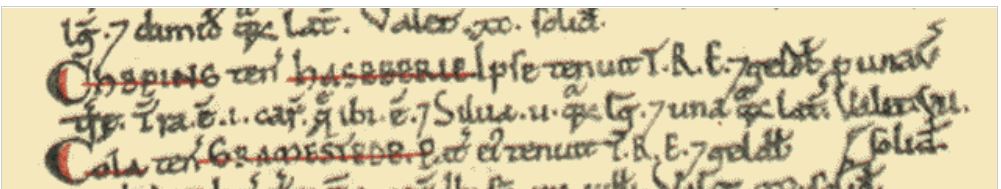

Cypping Holding

Cypping (held a third, small holding in Hazelbury) before 1066; it paid tax for 1 virgate of land. Land for 1 plough, which is there. Woodland 2 furlongs long and 1 furlong wide. Value 7s.

Cypping held the land both before and after 1066. It is difficult to be certain who Cypping was or where this land was situated although Hatt or Wadswick have been suggested.[24] Alternative suggestions are Wadswick Common (sometimes called Hazelbury Common) or the field to the south of Hazelbury.[25]

Cypping (held a third, small holding in Hazelbury) before 1066; it paid tax for 1 virgate of land. Land for 1 plough, which is there. Woodland 2 furlongs long and 1 furlong wide. Value 7s.

Cypping held the land both before and after 1066. It is difficult to be certain who Cypping was or where this land was situated although Hatt or Wadswick have been suggested.[24] Alternative suggestions are Wadswick Common (sometimes called Hazelbury Common) or the field to the south of Hazelbury.[25]

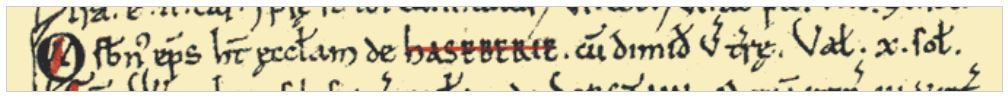

Hazelbury Church

Bishop Osbern has Hazelbury church with 1/2 virgate of land. Value 10s.

Osbern, Bishop of Exeter, was presumably granted this holding by King Edward before 1066 when he had served as a clerk to the king.[26] Osbern also held Chippenham Church in Edward's time. It has traditionally been assumed that the church held by Bishop Osbern was the Oulde Church on the Allen maps, either a proprietary church next to the manor house, or next to a settlement. The Wiltshire Historic Environment Record places the church site north of the manor on the basis of Kidston, who apparently found remains of the church.

Bishop Osbern has Hazelbury church with 1/2 virgate of land. Value 10s.

Osbern, Bishop of Exeter, was presumably granted this holding by King Edward before 1066 when he had served as a clerk to the king.[26] Osbern also held Chippenham Church in Edward's time. It has traditionally been assumed that the church held by Bishop Osbern was the Oulde Church on the Allen maps, either a proprietary church next to the manor house, or next to a settlement. The Wiltshire Historic Environment Record places the church site north of the manor on the basis of Kidston, who apparently found remains of the church.

The Domesday record is the first detailed reference to our area but the information opens up more questions than it resolves. Nonetheless the picture it gives of the area is fascinating. Locally, we have become obsessed with the word "Hazelbury" and the absence of a settlement recognisable as Box. This has spawned a narrative that a substantial Hazelbury was subsequently lost in the Black Death. For all its marvellous documentary evidence, GJ Kidston went looking for the history of his house and constructed a narrative to fit his needs in his History of the Manor of Hazelbury. He managed to complete six centuries of early medieval details by page 6 before turning to the feudal charters. This ignores the huge amount of detail given in the previous articles in this series.

References

[1] CP Lewis, Danish landowners in Wessex in 1066 in R Lavelle and S Roffey (eds) Danes in Wessex: The Scandinavian impact on Southern England c.800-c.1100, 2016, Oxbow, Oxford

[2] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, editors RB Pugh and Elizabeth Crittall, 1955, Oxford University Press, p.65

[3] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.8

[4] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.62-63

[5] CP Lewis, Danish landowners in Wessex in 1066 in R Lavelle and S Roffey (eds) Danes in Wessex: The Scandinavian impact on Southern England c.800-c.1100, 2016, Oxbow, Oxford

[6] For frequency see Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (PASE) website http://pase.ac.uk/index.html

[7] Von Feilitzen, Pre-Conquest Personal Names of Domesday Book, 1937. p. 313

[8] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.10

[9] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.67

[10] https://opendomesday.org/name/332600/leofnoth/

[11] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.143-147

[12] Michael Aston, Interpreting the Landscape, 1985, BT Batsford, p.34

[13] Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.153

[14] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.96

[15] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.43

[16] WG Hoskins, Local History in England, 1972, Longman Group, p.45 and www.buildinghistory.org/buildings/mills.shtml

[17] WG Hoskins, Local History in England, p.53

[18] Based on 1 acre = 1 furlong long x ⅒ furlong wide; 1 hide = 120 acres; 1 virgate = ¼ hide; 1 ox land = ½ virgate

[19] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.65

[20] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.127

[21] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.103

[22] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.65

[23] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.31

[24] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, p.8

[25] HR Hurst, DL Dartnall and C Fisher, ‘Excavations at Box Roman Villa, 1967-8’, The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine Volume 81, 1987, p.32

[26] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.34

[1] CP Lewis, Danish landowners in Wessex in 1066 in R Lavelle and S Roffey (eds) Danes in Wessex: The Scandinavian impact on Southern England c.800-c.1100, 2016, Oxbow, Oxford

[2] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, editors RB Pugh and Elizabeth Crittall, 1955, Oxford University Press, p.65

[3] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.8

[4] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.62-63

[5] CP Lewis, Danish landowners in Wessex in 1066 in R Lavelle and S Roffey (eds) Danes in Wessex: The Scandinavian impact on Southern England c.800-c.1100, 2016, Oxbow, Oxford

[6] For frequency see Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (PASE) website http://pase.ac.uk/index.html

[7] Von Feilitzen, Pre-Conquest Personal Names of Domesday Book, 1937. p. 313

[8] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.10

[9] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.67

[10] https://opendomesday.org/name/332600/leofnoth/

[11] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.143-147

[12] Michael Aston, Interpreting the Landscape, 1985, BT Batsford, p.34

[13] Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.153

[14] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.96

[15] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.43

[16] WG Hoskins, Local History in England, 1972, Longman Group, p.45 and www.buildinghistory.org/buildings/mills.shtml

[17] WG Hoskins, Local History in England, p.53

[18] Based on 1 acre = 1 furlong long x ⅒ furlong wide; 1 hide = 120 acres; 1 virgate = ¼ hide; 1 ox land = ½ virgate

[19] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.65

[20] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.127

[21] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.103

[22] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.65

[23] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.31

[24] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, p.8

[25] HR Hurst, DL Dartnall and C Fisher, ‘Excavations at Box Roman Villa, 1967-8’, The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine Volume 81, 1987, p.32

[26] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.34