No Rude Words Please: Thomas Bowdler’s Shakespeare Alan Payne September 2020

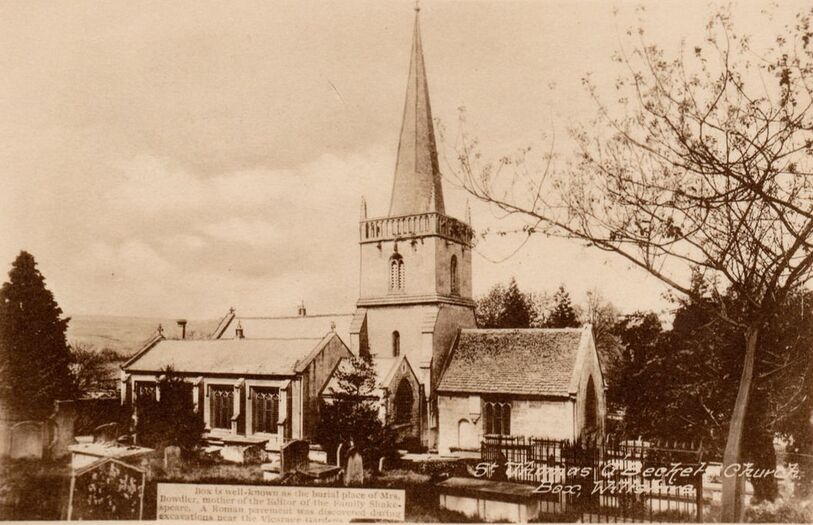

This postcard of Box Church is unusual for the caption it uses which reads: Box is well-known as the burial place of Mrs Bowdler, mother of the editor of the Family Shakespeare. It goes on to add, A Roman pavement was discovered during excavations near the Vicarage gardens. What does it all mean?

Like me, were you forced to study Shakespeare at school and found it impossible to read, not understanding many of the strange words? You are not alone and see how the memory comes back with the extract below.

Like me, were you forced to study Shakespeare at school and found it impossible to read, not understanding many of the strange words? You are not alone and see how the memory comes back with the extract below.

What Did Shakespeare Really Mean?

According to the Royal Shakespeare Company there are two meanings to much of Shakespeare’s language. They illustrated this in a passage from Henry IV, Part II, Act 2, Scene 1. Don’t worry if the original is a bit difficult, because they suggest two modern translations and please don’t blame me for the words they use:[1]

Original

MISTRESS QUICKLY: Take heed of him: he stabbed me in mine own house, and that most beastly. He cares not what mischief he doth, if his weapon be out. He will foin like any devil. He will spare neither man, woman, nor child.

FANG: If I can close with him, I care not for his thrust.

MISTRESS QUICKLY: No, nor I neither. I'll be at your elbow.

FANG: If I but fist him once, if he come but within my vice --

Translation 1 (Polite version)

Quickly: Beware him. He financially hurt me in my own inn in a beastly way. He doesn’t care what he does when armed with his sword. He thrusts it like a devil, sparing no one.

Fang: If I can fight him, I don’t care about his thrusts.

Quickly: Neither do I, I’ll advance with you.

Fang: If I punch him a little, he’ll be in my grip.

WARNING The alternative translation proposed by the RSC (below) contains overtly sexual language.

Some readers may be offended by the crude sexual words:

Quickly: Beware him. He sexually penetrated my v_ _ _ _ a (belly) in a beastly way. He doesn’t care what he does if his p_ _ _ s (manhood) is aroused, he will thrust like a devil, sparing no-one.

Fang: If I can have a sexual encounter with him, I don’t care about his sexual preference.

Quickly: Neither do I, I’ll come with you.

Fang: If I m_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ e (stimulate) him a little, his orgasm is in my control.

The point is that Shakespeare was an exponent of the art of sexual double entendre, apparent to his contemporary audiences but the references lost in the passage of time, although still evident to Georgian ears. If I had known about this interpretation, I might even have enjoyed Shakespeare more as a teenager.

Other parts of Shakespeare’s imagery are more vulgar than sexual, such as Dromio in The Comedy of Errors: A man may

break a word with you sire, and words are but wind. Ay, and break it in your face, so he break it not behind. Other language has mildly blasphemous words that we might use ourselves but wouldn’t want our children to repeat, such as Lady Macbeth:

Out, damned spot!

According to the Royal Shakespeare Company there are two meanings to much of Shakespeare’s language. They illustrated this in a passage from Henry IV, Part II, Act 2, Scene 1. Don’t worry if the original is a bit difficult, because they suggest two modern translations and please don’t blame me for the words they use:[1]

Original

MISTRESS QUICKLY: Take heed of him: he stabbed me in mine own house, and that most beastly. He cares not what mischief he doth, if his weapon be out. He will foin like any devil. He will spare neither man, woman, nor child.

FANG: If I can close with him, I care not for his thrust.

MISTRESS QUICKLY: No, nor I neither. I'll be at your elbow.

FANG: If I but fist him once, if he come but within my vice --

Translation 1 (Polite version)

Quickly: Beware him. He financially hurt me in my own inn in a beastly way. He doesn’t care what he does when armed with his sword. He thrusts it like a devil, sparing no one.

Fang: If I can fight him, I don’t care about his thrusts.

Quickly: Neither do I, I’ll advance with you.

Fang: If I punch him a little, he’ll be in my grip.

WARNING The alternative translation proposed by the RSC (below) contains overtly sexual language.

Some readers may be offended by the crude sexual words:

Quickly: Beware him. He sexually penetrated my v_ _ _ _ a (belly) in a beastly way. He doesn’t care what he does if his p_ _ _ s (manhood) is aroused, he will thrust like a devil, sparing no-one.

Fang: If I can have a sexual encounter with him, I don’t care about his sexual preference.

Quickly: Neither do I, I’ll come with you.

Fang: If I m_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ e (stimulate) him a little, his orgasm is in my control.

The point is that Shakespeare was an exponent of the art of sexual double entendre, apparent to his contemporary audiences but the references lost in the passage of time, although still evident to Georgian ears. If I had known about this interpretation, I might even have enjoyed Shakespeare more as a teenager.

Other parts of Shakespeare’s imagery are more vulgar than sexual, such as Dromio in The Comedy of Errors: A man may

break a word with you sire, and words are but wind. Ay, and break it in your face, so he break it not behind. Other language has mildly blasphemous words that we might use ourselves but wouldn’t want our children to repeat, such as Lady Macbeth:

Out, damned spot!

Bowdler Family of Ashley

We know that the family lived at Ashley from at least 1752 when Thomas senior (1706-1785) and his wife Elizabeth Stuart (1717-1797) gave birth to their third child, Henrietta Maria. The family were wealthy and acquired a plot in Box Churchyard and later erected memorial epitaphs inside the Church. We don’t know where they lived in Ashley, nor their status or the source of their money but we can speculate. Elizabeth was the daughter and co-heir of Sir John Cotton of Conington in the county of Huntingdonshire, the last Baronet of a line established in 1611. The first baron had the most magnificent collection of books and manuscripts in Britain, including the Lindisfarne Gospels and many unique Anglo-Saxon manuscripts including the only surviving copy of Beowulf. The collection ultimately became the basis of the British Library. There were no male heirs on Sir John’s death in 1752 and his daughters inherited the assets, part of which came under the control of Elizabeth’s husband, Thomas senior.

We know that the family lived at Ashley from at least 1752 when Thomas senior (1706-1785) and his wife Elizabeth Stuart (1717-1797) gave birth to their third child, Henrietta Maria. The family were wealthy and acquired a plot in Box Churchyard and later erected memorial epitaphs inside the Church. We don’t know where they lived in Ashley, nor their status or the source of their money but we can speculate. Elizabeth was the daughter and co-heir of Sir John Cotton of Conington in the county of Huntingdonshire, the last Baronet of a line established in 1611. The first baron had the most magnificent collection of books and manuscripts in Britain, including the Lindisfarne Gospels and many unique Anglo-Saxon manuscripts including the only surviving copy of Beowulf. The collection ultimately became the basis of the British Library. There were no male heirs on Sir John’s death in 1752 and his daughters inherited the assets, part of which came under the control of Elizabeth’s husband, Thomas senior.

The family set up home in Box after the death of Elizabeth’s father but they lasted only one generation. They moved to Bath sometime between the death of Thomas senior in 1785 and that of their daughter Henrietta Maria in 1797. The connection with Box continued, however, and most of the family were buried in the vault in Box, including the parents and several of their children.

Thomas and Elizabeth had six children, of whom the youngest, Thomas, is the subject of this article. He had a medical degree from Edinburgh University and is sometimes called Dr Bowdler but he appears to have given up medicine after contracting an illness on a European Tour in 1781.[2] He scarcely settled thereafter, doing prison reform work, playing competitive chess to a high standard, moving to St Boniface, Isle of Wight, and marrying for the first time in 1806 when he was 52. The marriage failed and the couple separated, childless. Thomas moved to Swansea in 1811 to the Rhyddings.[3] He was buried there at All Saints Parish Church, Oystermouth where his headstone reads:

Sacred to the memory of Thomas Bowdler, Esq, youngest son of Thomas Bowdler, Esq, of Ashley, near Bath, who was born at Ashley, July 11 1754 and died at Rhyddings, near Swansea February 24 1825.[4]

He was a sincere member of the established Church of England, putting away lying, speak every man truth with his neighbour for we are members one of another. Above all things, truth beareth away the victory.[5]

Thomas and Elizabeth had six children, of whom the youngest, Thomas, is the subject of this article. He had a medical degree from Edinburgh University and is sometimes called Dr Bowdler but he appears to have given up medicine after contracting an illness on a European Tour in 1781.[2] He scarcely settled thereafter, doing prison reform work, playing competitive chess to a high standard, moving to St Boniface, Isle of Wight, and marrying for the first time in 1806 when he was 52. The marriage failed and the couple separated, childless. Thomas moved to Swansea in 1811 to the Rhyddings.[3] He was buried there at All Saints Parish Church, Oystermouth where his headstone reads:

Sacred to the memory of Thomas Bowdler, Esq, youngest son of Thomas Bowdler, Esq, of Ashley, near Bath, who was born at Ashley, July 11 1754 and died at Rhyddings, near Swansea February 24 1825.[4]

He was a sincere member of the established Church of England, putting away lying, speak every man truth with his neighbour for we are members one of another. Above all things, truth beareth away the victory.[5]

Memorials in Box

There are two memorials to the family in Box: a chest tomb and a memorial plaque. The Bowdler chest tomb still exists in the churchyard, close to Springfield Cottage, seen above. It is large (a double chest tomb), typical of the late 1700s with oval plaques on each side. There are Inscriptions to T and ES Bowdler, but the rest is indecipherable.

There are two memorials to the family in Box: a chest tomb and a memorial plaque. The Bowdler chest tomb still exists in the churchyard, close to Springfield Cottage, seen above. It is large (a double chest tomb), typical of the late 1700s with oval plaques on each side. There are Inscriptions to T and ES Bowdler, but the rest is indecipherable.

|

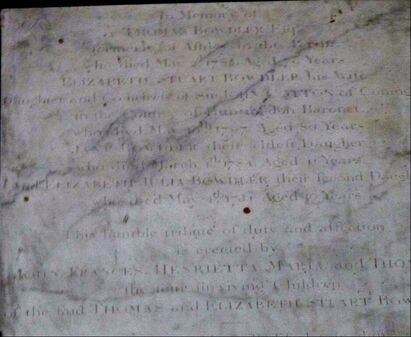

The memorial plaque on the wall of the nave in St Thomas à

Becket Church (courtesy Carol Payne) has survived better. It reads: In memory of Thomas Bowdler, Esq, formerly of Ashley in the parish who died May 2nd 1785 aged 79 years; Elizabeth Stuart Bowdler, his wife, daughter and co-heir of Sir John Cotton of Conington in the county of Huntington (sic), Baronet, who died May 10th 1797 aged 80 years; Jane Bowdler their eldest daughter who died March 4th 1784 aged 44 years; and Elizabeth Julia Bowdler their second daughter who died May 4th 1751 aged 10 years. This humble tribute of duty and affection is erected by John, Francis, Henrietta Maria and Thomas, the four surviving children of the said Thomas and Elizabeth Stuart Bowdler. |

The sculptured marble shall dissolve in dust And fame and wealth and honours pass away Not such the triumphs of the good and just Nor such the glories of eternal day They therefore shall live when ages are no more With never-fading lustre full shall shine Go then to Heaven devote the almighty power And know who’er thou art the prize is thine.

|

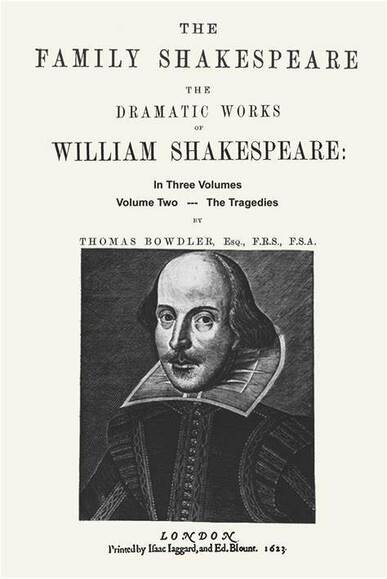

The Family Shakespeare

The comfortable Georgian world reached its full expression in the early 1800s when coarse vulgarity gave way to a gentility verging on prudishness. It was a sentiment appreciated by the Victorians. The Bowdler family who lived at Ashley decided to do something about the risqué bits in Shakespeare by deleting or re-writing them in a Family Shakespeare that could with propriety be read aloud in a family. The revisions of Shakespeare’s works weren’t Thomas’ original idea and it is claimed that he was helped by his sisters.[6] The first clean-up of Shakespeare was probably edited by Henrietta Maria in 1807, although published anonymously, and it comprised twenty of the plays. It was claimed that her father, Thomas senior, had omitted or altered unsuitable passages when reading to his children and Henrietta did likewise in print. The 1807 edition didn’t make much impact. The younger sibling Thomas Bowdler extended the range to include all of the plays and published the work in ten volumes in 1818. This became a best seller (and is still in print) and coined the term to bowdlerise.[7] Right: Frontispiece after Thomas Bowdler had taken over from Henrietta (courtesy Wikipedia) |

|

Thomas wasn’t buried in Box but in Oystermouth (seen left courtesy Ian Bowdler of www.bowdlers.com). He didn’t forget his roots, however, and bequeathed £25 to the poor of Oystermouth and Box.[8] He also edited Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire to remove anti-religious sentiments and this work was published posthumously in 1827 by his nephew.[9] Apparently, a bust of Thomas Bowdler existed at the Royal Institution of South Wales, Swansea, where he was feted as one of Oystermouth’s most significant residents. We can see from the alternative translation by the Royal Shakespeare Company that some passages could offend our modern ears and would be most difficult to discuss with children and young adults, even in the modified version I have used. But generally, Thomas Bowdler’s standing has diminished, and he is now seen as a self-appointed hack who vandalised original works. The word bowdlerise is often derogatory, as evidenced by a student proposal to commemorate the 1954 bi-centenary of his birth by placing a fig-leaf on his grave rather than a wreath.[10] Sic transit gloria mundi. |

Bowdler Family Tree

Thomas senior (1706-1785), Esq, and his wife Elizabeth Stuart (1717- died 10 May 1797 at Bath). Children:

Jane (1743 - died 4 March 1784 at Box)

Elizabeth Julia (1744 - died 1754 at Box)

John (18 March 1746-30 June 1823)

Frances (1748- died 1836 in Bath, buried in Box)

Henrietta Maria (baptised 22 January 1752 - 1830)

Thomas (11 July 1754 -1825)

Thomas senior (1706-1785), Esq, and his wife Elizabeth Stuart (1717- died 10 May 1797 at Bath). Children:

Jane (1743 - died 4 March 1784 at Box)

Elizabeth Julia (1744 - died 1754 at Box)

John (18 March 1746-30 June 1823)

Frances (1748- died 1836 in Bath, buried in Box)

Henrietta Maria (baptised 22 January 1752 - 1830)

Thomas (11 July 1754 -1825)

References

[1] https://www.rsc.org.uk/SHAKESPEARE/LANGUAGE/SLANG-AND-SEXUAL-LANGUAGE

[2] The Scotsman, 13 June 1946

[3] South Wales Daily News, 24 January 1879

[4] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 16 June 1945

[5] See www.bowdlers.com

[6] John Britton, Beauties of Wiltshire, 1825, p.192

[7] Ken Watts, The Wiltshire Cotswolds, 2007, The Hobnob Press, p.196

[8] South Wales Daily News, 24 January 1879

[9] The Globe, 10 May 1827

[10] The Western Mail, 9 April 1954

[1] https://www.rsc.org.uk/SHAKESPEARE/LANGUAGE/SLANG-AND-SEXUAL-LANGUAGE

[2] The Scotsman, 13 June 1946

[3] South Wales Daily News, 24 January 1879

[4] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 16 June 1945

[5] See www.bowdlers.com

[6] John Britton, Beauties of Wiltshire, 1825, p.192

[7] Ken Watts, The Wiltshire Cotswolds, 2007, The Hobnob Press, p.196

[8] South Wales Daily News, 24 January 1879

[9] The Globe, 10 May 1827

[10] The Western Mail, 9 April 1954