Boundaries of Early Medieval Box Alan Payne and Jonathan Parkhouse, December 2020

Some historians have claimed a connection between Roman villa land units and later boundaries of Saxon estates, parishes and field areas and cite evidence from Wrington, North Somerset.[1] But we lack good evidence to define the bounds of most Roman-British villa estates and this argument remains unproven at Box as at other sites.

There are no Saxon charters marking out Box, but there are two which define the boundary line for neighbouring areas: one for Bathford in 957 and the other for Bradford-on-Avon in 1001. Through these charters (document recording land grants) we can construct some of Box’s Saxon boundaries, not just the historic ones of the Lid Brook and the old Roman Road.

There are no Saxon charters marking out Box, but there are two which define the boundary line for neighbouring areas: one for Bathford in 957 and the other for Bradford-on-Avon in 1001. Through these charters (document recording land grants) we can construct some of Box’s Saxon boundaries, not just the historic ones of the Lid Brook and the old Roman Road.

Border with Bathford, 957

In the second half of the 900s, the king appropriated and re-distributed many lands which previously had been given to thegns (lords), notwithstanding that they had been designated as book land (land held by charter) to give them a permanence. In 957, King Eadwig made a grant of 10 hides of land at Bathford to St Peter's Abbey, Bath at the request of his sacerdos (priest) Wulfgar.[2] The charter is believed to be genuine, although there were many forged documents at this time. In passing, we might note that Bath Abbey was reformed as a monastic community in the late 900s.[3]

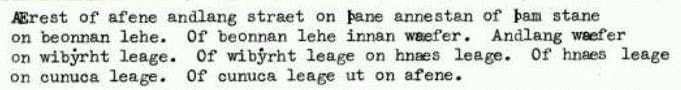

An extract of the extensive charter reads in translation: These are the land-boundaries at BATHFORD. First from the Avon along the street to the single stone; from the stone to Beonna’s wood; from Beonna’s wood to the wæfer [Weavern, the name for By Brook]; along the wæfer to Wibyrht’s wood; from Wibyrht’s wood to hnæs wood; from hnæs wood to cunuca wood; from cunuca wood to the Avon.[4]

In the second half of the 900s, the king appropriated and re-distributed many lands which previously had been given to thegns (lords), notwithstanding that they had been designated as book land (land held by charter) to give them a permanence. In 957, King Eadwig made a grant of 10 hides of land at Bathford to St Peter's Abbey, Bath at the request of his sacerdos (priest) Wulfgar.[2] The charter is believed to be genuine, although there were many forged documents at this time. In passing, we might note that Bath Abbey was reformed as a monastic community in the late 900s.[3]

An extract of the extensive charter reads in translation: These are the land-boundaries at BATHFORD. First from the Avon along the street to the single stone; from the stone to Beonna’s wood; from Beonna’s wood to the wæfer [Weavern, the name for By Brook]; along the wæfer to Wibyrht’s wood; from Wibyrht’s wood to hnæs wood; from hnæs wood to cunuca wood; from cunuca wood to the Avon.[4]

At first glance the terms of the charter don’t seem very helpful. Most of it is written in formulaic language common in the Latin of medieval charters with dedication and linguistic repetition and witnessed by a score of bishops, abbots and earls. The boundary details are in Old English, which was a common format, probably copied by monastic scribes from earlier documents.[5]

The boundary described in the charter is still the boundary between Bathford and Box deeply rural, running along field borders. The territory is largely defined by significant natural features, the River Avon, the By Brook and the Fosse Way (called straet) from Rodney Farm to The Mount. It is interesting that the single stone has reminiscences of the Three Sire Stones commemorated at Colerne Down. Beonna’s wood has been identified as Benlands (Bennels) at Shockerwick, hnæs is sometimes translated as ridge-end meaning Ashley Wood and cunuca has been taken to be Conkwell.[6]

The boundary described in the charter is still the boundary between Bathford and Box deeply rural, running along field borders. The territory is largely defined by significant natural features, the River Avon, the By Brook and the Fosse Way (called straet) from Rodney Farm to The Mount. It is interesting that the single stone has reminiscences of the Three Sire Stones commemorated at Colerne Down. Beonna’s wood has been identified as Benlands (Bennels) at Shockerwick, hnæs is sometimes translated as ridge-end meaning Ashley Wood and cunuca has been taken to be Conkwell.[6]

Border with Bradford-on-Avon, 1001

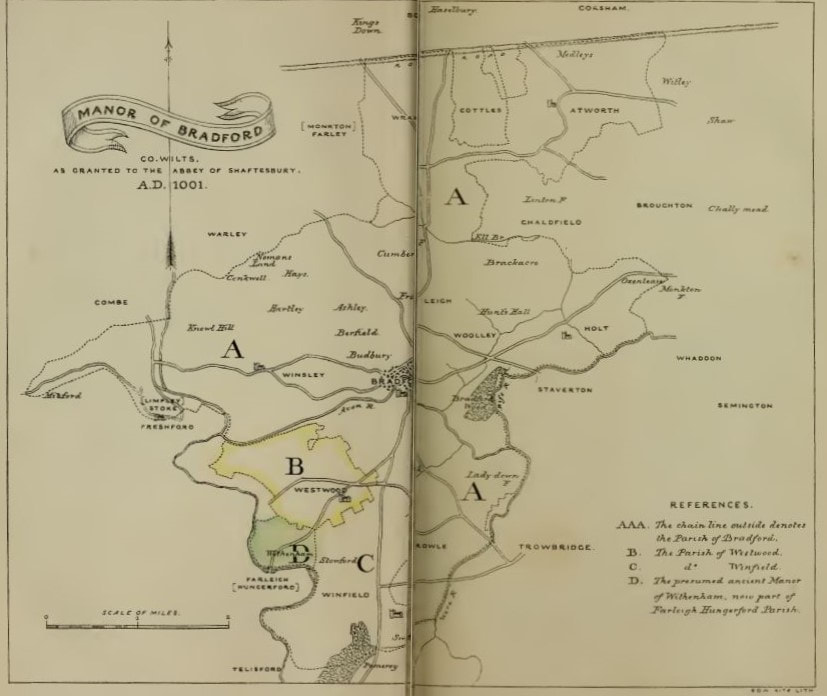

A later charter records the southern boundary between Box and Bradford-on-Avon.[7] The period around the year 1000 was associated with the creation of various nunneries, of which there were a large number in Wiltshire, partly inspired by royal wives, widows and siblings. The Saxon church of St Laurence at Bradford-on-Avon is a fine example of the female influence. The vill and manor of Bradford was donated to the nuns at Shaftsbury to house the remains of Edward the Martyr in the event of Viking attack. The charter was made at a time of many problems in Wiltshire. The Viking army was joined by another group led by the Dane Pallig Tokesen and his forces from Devon. Pallig was well-connected to the Danish royal family through his wife, Gunhilde, daughter of Harold Bluetooth and sister of Sweyn Forkbeard. The Saxon forces led by ealdorman Aelfric capitulated to the Danish forces.[8]

The charter dated 1001 recorded the precise lands which were gifted to the nunnery and, in so doing, defined the boundary of Bradford and Box:

... and so by the Abbot’s boundary to Alfgares boundary at Farnleghe (Farleigh) and forth along his boundary until it comes to the King’s boundary at Heselberi; from here it goes forth along the King’s boundary until it comes to Alfgares boundary at Attenwrthe (Atworth) and forth along his boundary until it comes to Lefwines boundary at Coseham (Corsham).

A later charter records the southern boundary between Box and Bradford-on-Avon.[7] The period around the year 1000 was associated with the creation of various nunneries, of which there were a large number in Wiltshire, partly inspired by royal wives, widows and siblings. The Saxon church of St Laurence at Bradford-on-Avon is a fine example of the female influence. The vill and manor of Bradford was donated to the nuns at Shaftsbury to house the remains of Edward the Martyr in the event of Viking attack. The charter was made at a time of many problems in Wiltshire. The Viking army was joined by another group led by the Dane Pallig Tokesen and his forces from Devon. Pallig was well-connected to the Danish royal family through his wife, Gunhilde, daughter of Harold Bluetooth and sister of Sweyn Forkbeard. The Saxon forces led by ealdorman Aelfric capitulated to the Danish forces.[8]

The charter dated 1001 recorded the precise lands which were gifted to the nunnery and, in so doing, defined the boundary of Bradford and Box:

... and so by the Abbot’s boundary to Alfgares boundary at Farnleghe (Farleigh) and forth along his boundary until it comes to the King’s boundary at Heselberi; from here it goes forth along the King’s boundary until it comes to Alfgares boundary at Attenwrthe (Atworth) and forth along his boundary until it comes to Lefwines boundary at Coseham (Corsham).

| bradford-on-avon_boundary_1001.docx | |

| File Size: | 219 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

As with the Bathford charter, the bulk of the Bradford charter is in Latin and the boundary details in Old English. Both charters use identifiable landmarks such as streams and Roman roads. This charter identifies the boundary from the Farleigh road approximately at the Golf Club all the way to Atworth. The charter calls this area Hazelbury and describes the boundary as the King’s boundary (the kinges imare at Heselberi). It could be interpreted that the king owned all the land to the north of the road or that Hazelbury was a more extensive area than today, including the Kings Down.

Conclusion

Clearly, it would answer many questions about the origin of Box if there had been a charter defining the areas not covered by the Bathford or Bradford documents. There isn't which, in itself, bring further questions about whether an identifiable location existed which might resemble our later area. Without evidence to the contrary, it remains likely that Box was inhabited and farmed but not recognised as a self-contained unit with an identifiable community.

Clearly, it would answer many questions about the origin of Box if there had been a charter defining the areas not covered by the Bathford or Bradford documents. There isn't which, in itself, bring further questions about whether an identifiable location existed which might resemble our later area. Without evidence to the contrary, it remains likely that Box was inhabited and farmed but not recognised as a self-contained unit with an identifiable community.

References

[1] Martin Jones, England Before Domesday, 1986, BT Batsford, p.153

[2] Recorded as S 643 http://www.esawyer.org.uk/charter/643.html#

[3] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.218

[4] Commander AS Craig, 1987, www.bathfordsociety.org.uk/content/pdfs/manor_and_tithing_of_shockerwick_full.pdf

[5] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.13

[6] The ash is deemed by some to have been a sacred tree in Saxon times (Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol 5, 1859, p.15

[7] Recorded as S 899 http://www.esawyer.org.uk/charter/899.html

[8] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.135

[1] Martin Jones, England Before Domesday, 1986, BT Batsford, p.153

[2] Recorded as S 643 http://www.esawyer.org.uk/charter/643.html#

[3] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.218

[4] Commander AS Craig, 1987, www.bathfordsociety.org.uk/content/pdfs/manor_and_tithing_of_shockerwick_full.pdf

[5] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.13

[6] The ash is deemed by some to have been a sacred tree in Saxon times (Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol 5, 1859, p.15

[7] Recorded as S 899 http://www.esawyer.org.uk/charter/899.html

[8] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.135