|

Botcherby Family Photos and family research Claire Botcherby December 2018 This charming photo was taken in the 1920s, nearly a century ago. It shows an ordinary, middle-aged couple that we might see out and about today but that wasn't the perception of them in Box during the First World War. The Botcherby family were at the centre of a dramatic event in the village, involving accusations of lack of patriotism. The photograph shows Reginald and his wife Arnie Botcherby who lived in Box from the shortly after 1901 until the middle of the First World War, renting a cottage at Ashley for the last part of that time. Reginald worked for two local Members of Parliament, a trusted and well-respected member of the local community. The war altered all of that and caused the family to leave the village. Before we get to those dramatic events, it might be useful to set the background of Reginald Botcherby and his wife Arnie. Left: Reginald and Arnie Botcherby in the 1920s. |

|

Reginald was born in Hampstead in 1877, the third son of George and Laura Botcherby. On the early death of his father, he had to leave school at the age of sixteen and started life as a clerk, probably at I & R Morley’s London warehouse, working his way up. By his mid-twenties to become Private Secretary for the Liberal MP Charles Morley (1847 - 1917) at Shockerwick House. Here, he would have dealt with the correspondence of the Member of Parliament and with running the estate. An important part of his job would have been implementing decisions and liaising between Charles Morley and the tenants and staff at Shockerwick.

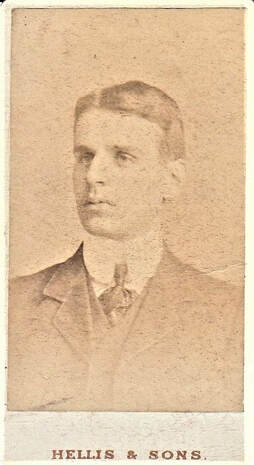

He was a keen cricketer. In 1896, the Ham and High, Hampstead’s local newspaper, reported that RH Botcherby bowled in good form, taking eight wickets at a cost of eighteen runs for Willoughby (Hampstead YMCA).[1] At Box, he is known to have played for the local Married Men Team against the Single Men. On 14 April 1906, he was unable to play through illness. George Hale, perhaps team captain on that occasion, wrote to him from his Shockerwick Stables address to confirm that the married men had upheld their reputation by beating the single men by about 50 runs. Right: Reginald in his late teens |

Reginald worked for the Morleys for many years, moving to Box at around the turn of the century. At first, he lived in a small cottage in Box village before moving, in about 1908, to Ashley Cottage, a house tenanted from the Northeys as part of the Ashley Estate. Charles Morley will have relied on him for the running of the house and estate at Shockerwick since he will have been fully occupied as the Liberal Member of Parliament for Breconshire from 1895 to 1906, and as a Justice of the Peace variously for Wiltshire, Somerset and Berkshire. Occasionally, Reginald accompanied Charles to London and elsewhere in the country as, and when, required.

As part of his role, in 1903 Reginald organised the village Sunday School outing on behalf of the Morley family. It was a considerable undertaking with local children conveyed to Shockerwick House by eleven horse-drawn wagons to meet up with the band of the Sutcliffe Industrial School leading a procession of wagons. This was followed by tea in the grounds from four immense urns with more than three gallons of milk and subscriptions for prizes from 34 Box residents.[2]

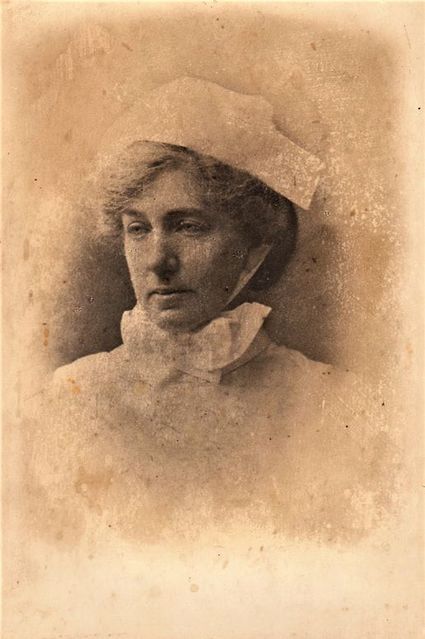

The following year, Reginald married Gertrude Elizabeth Jeboult from Exeter. Two years later, their son Paul was born. Gertrude (always known as Arnie) was the youngest daughter of Henry Pounsbery Jeboult, a fine china, glass and art-pottery merchant and wholesaler with premises in the centre of Exeter. She was a keen cellist and also played the piano. After her father’s death, she started training as a nurse in 1898 at the Hampstead Hospital in London. The 1901 census shows her as still working there three years before her marriage to Reginald.

After Charles’s retirement as a Member of Parliament in 1906, Reginald continued to be employed as his secretary and estate manager while also undertaking duties at Ashley House for Sidney Robinson, Charles’s successor in the Brecon constituency. On hearing that Reginald had joined up, Sidney Robinson wrote a sympathetic letter, recognising his need to volunteer in the circumstances, and offering to keep his beloved Bechstein piano in the monkey house where it will be kept dry and happy.

Charles, likewise, kept up correspondence with Reginald. After Reginald had left in 1916 to join up, Charles states in a letter that All is going on here much as usual. Bendall runs the electric light with, I fancy, an occasional look in from Donald. Our Austin car has broken down so we have got the Renaut (sic) from London that was my brother’s.

Samuel Morley

Charles Morley was a partner in the firm of I & R Morley, established in 1797 and expanded greatly under the control of his father, Samuel Morley. The firm, involved in the manufacture and warehousing of woollen goods, was typical of the vertical industrial organisation used by people who rose to enormous wealth in the Industrial Revolution, reputedly employing 10,000 people in 1866.[3]

Samuel was relentless in his dedication to the family business. He bought a factory in Manvers Street, Nottingham, and spent £27,000 fitting it out. In 1874 it was burnt to the ground but, undaunted, Samuel rebuilt it even bigger. He was elected a Liberal Member of Parliament for Nottingham and between 1868 and 1885 MP for Bristol. He was a strong non-conformist, supported the abolition of slavery (and freed the real-life hero of Uncle Tom's Cabin), became the proprietor of the Liberal newspaper, The Daily News, endowed Morley College for adult education, supported The Old Vic, London, introduced an Old Age pension scheme for his employees and joined with William Booth in founding the Salvation Army. It is a staggering list of achievements for a single person. He declined a peerage from Prime Minister Gladstone because he didn't want to receive personal advantage from his work and he died in 1886. A statue of him was built in Parliament Street, Nottingham, by public subscription, where he was described as Merchant, Philanthropist, Member of Parliament, Friend of Children, Social Reformer, Christian Citizen.

The Morleys also had a large warehouse at 1 Wood Street on the corner with Gresham Street in the City of London. Reginald’s father, George Botcherby, ran his textiles business from a warehouse just a few yards away on the other side of Wood Street. George was a Freeman of the City of London, as was Charles Morley and the two may have known one another through their business dealings. George and Charles also shared a great interest in music and it is possible that they could have attended the same City concerts and recitals, or belonged to a London musical society, quite apart from any business relationship. Reginald, too, was musical along with his three brothers; all four siblings being organists.

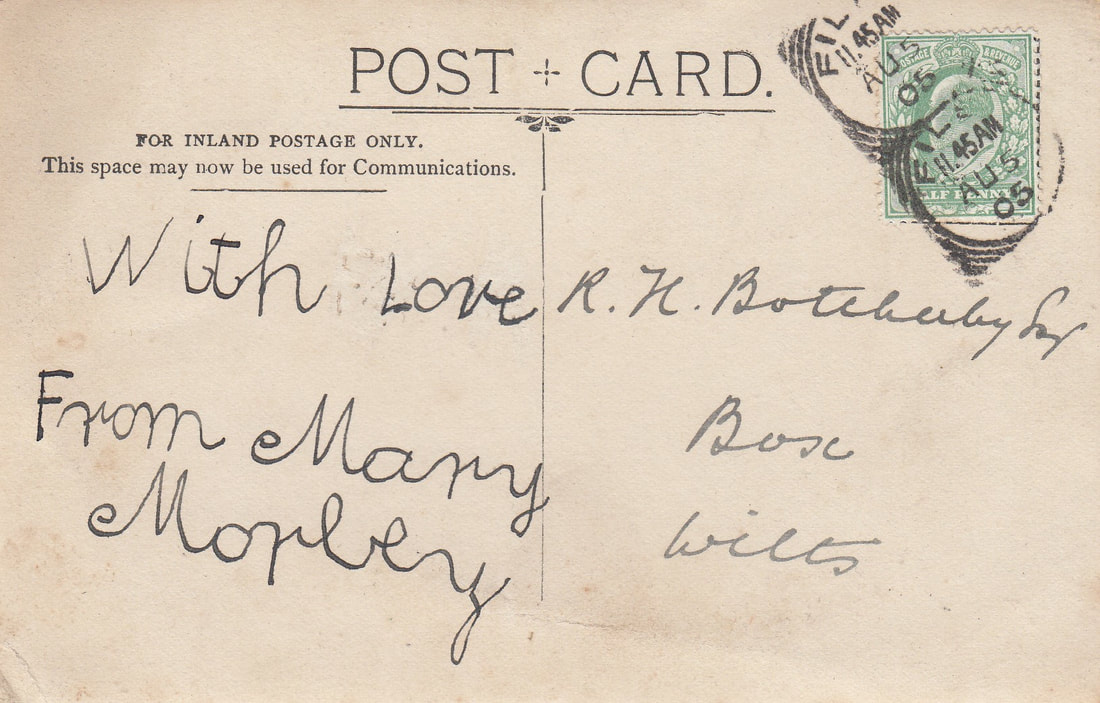

Reginald’s grandfather had been a piano manufacturer and piano teacher in Hackney. With both the Morley and Botcherby families having a strong Hackney connection, it is possible that he may have taught a young Charles Morley to play. All conjecture! It seems there was always a good relationship between Reginald and the Morley family, as evidenced by the attached postcard from a young Mary Morley to Reginald while on holiday at Filey, North Yorkshire in 1905. Fourteen years later, Mary married Charles Peter Julius Layard from Somerset who became a Colonel in the Royal Artillery. They lived at Corton Denham House on the Somerset-Dorset border and had two daughters.

The following year, Reginald married Gertrude Elizabeth Jeboult from Exeter. Two years later, their son Paul was born. Gertrude (always known as Arnie) was the youngest daughter of Henry Pounsbery Jeboult, a fine china, glass and art-pottery merchant and wholesaler with premises in the centre of Exeter. She was a keen cellist and also played the piano. After her father’s death, she started training as a nurse in 1898 at the Hampstead Hospital in London. The 1901 census shows her as still working there three years before her marriage to Reginald.

After Charles’s retirement as a Member of Parliament in 1906, Reginald continued to be employed as his secretary and estate manager while also undertaking duties at Ashley House for Sidney Robinson, Charles’s successor in the Brecon constituency. On hearing that Reginald had joined up, Sidney Robinson wrote a sympathetic letter, recognising his need to volunteer in the circumstances, and offering to keep his beloved Bechstein piano in the monkey house where it will be kept dry and happy.

Charles, likewise, kept up correspondence with Reginald. After Reginald had left in 1916 to join up, Charles states in a letter that All is going on here much as usual. Bendall runs the electric light with, I fancy, an occasional look in from Donald. Our Austin car has broken down so we have got the Renaut (sic) from London that was my brother’s.

Samuel Morley

Charles Morley was a partner in the firm of I & R Morley, established in 1797 and expanded greatly under the control of his father, Samuel Morley. The firm, involved in the manufacture and warehousing of woollen goods, was typical of the vertical industrial organisation used by people who rose to enormous wealth in the Industrial Revolution, reputedly employing 10,000 people in 1866.[3]

Samuel was relentless in his dedication to the family business. He bought a factory in Manvers Street, Nottingham, and spent £27,000 fitting it out. In 1874 it was burnt to the ground but, undaunted, Samuel rebuilt it even bigger. He was elected a Liberal Member of Parliament for Nottingham and between 1868 and 1885 MP for Bristol. He was a strong non-conformist, supported the abolition of slavery (and freed the real-life hero of Uncle Tom's Cabin), became the proprietor of the Liberal newspaper, The Daily News, endowed Morley College for adult education, supported The Old Vic, London, introduced an Old Age pension scheme for his employees and joined with William Booth in founding the Salvation Army. It is a staggering list of achievements for a single person. He declined a peerage from Prime Minister Gladstone because he didn't want to receive personal advantage from his work and he died in 1886. A statue of him was built in Parliament Street, Nottingham, by public subscription, where he was described as Merchant, Philanthropist, Member of Parliament, Friend of Children, Social Reformer, Christian Citizen.

The Morleys also had a large warehouse at 1 Wood Street on the corner with Gresham Street in the City of London. Reginald’s father, George Botcherby, ran his textiles business from a warehouse just a few yards away on the other side of Wood Street. George was a Freeman of the City of London, as was Charles Morley and the two may have known one another through their business dealings. George and Charles also shared a great interest in music and it is possible that they could have attended the same City concerts and recitals, or belonged to a London musical society, quite apart from any business relationship. Reginald, too, was musical along with his three brothers; all four siblings being organists.

Reginald’s grandfather had been a piano manufacturer and piano teacher in Hackney. With both the Morley and Botcherby families having a strong Hackney connection, it is possible that he may have taught a young Charles Morley to play. All conjecture! It seems there was always a good relationship between Reginald and the Morley family, as evidenced by the attached postcard from a young Mary Morley to Reginald while on holiday at Filey, North Yorkshire in 1905. Fourteen years later, Mary married Charles Peter Julius Layard from Somerset who became a Colonel in the Royal Artillery. They lived at Corton Denham House on the Somerset-Dorset border and had two daughters.

Charles Morley of Shockerwick

Charles was third of five sons of Samuel Morley, sufficiently wealthy to buy Shockerwick House, Bathford, in the 1880s. He was born in Hackney, where Reginald’s father and grandfather had also lived and it may be that a long-standing acquaintance between the families eventually led to Reginald’s employment with Charles.

Besides being a partner in his family’s high-class hosiery and knitwear firm of I & R Morley of Nottingham, Charles was Honorary Secretary of the Royal College of Music from its founding in 1882 until his death in 1917.

In his time at the RCM, Charles provided the initial contribution on which the RCM Union of past and present students was set up in 1906. Later, in 1910, he initiated a fund to provide financial support to students in difficulty.

Charles was third of five sons of Samuel Morley, sufficiently wealthy to buy Shockerwick House, Bathford, in the 1880s. He was born in Hackney, where Reginald’s father and grandfather had also lived and it may be that a long-standing acquaintance between the families eventually led to Reginald’s employment with Charles.

Besides being a partner in his family’s high-class hosiery and knitwear firm of I & R Morley of Nottingham, Charles was Honorary Secretary of the Royal College of Music from its founding in 1882 until his death in 1917.

In his time at the RCM, Charles provided the initial contribution on which the RCM Union of past and present students was set up in 1906. Later, in 1910, he initiated a fund to provide financial support to students in difficulty.

|

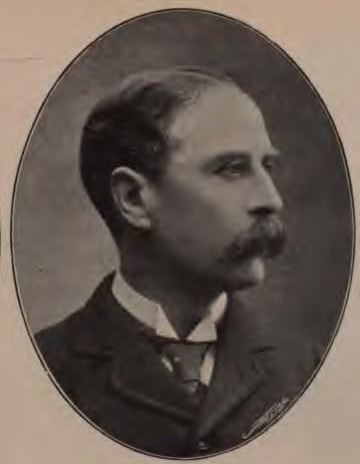

The Morley family were staunch Liberals and David Lloyd George is known to have visited Charles at Shockerwick House on several occasions. In a letter to Reginald in December 1916, Charles commented that It is certainly interesting to notice that the Tories are receiving LG [Lloyd George] with open arms while the Liberals satisfaction is certainly more restrained. Well, if our new PM [Lloyd George became Prime Minister on 6 December 1916] is able to infuse more vigour into the prosecution of the war, more power to him, for nothing else matters much at present. Lloyd George, famed for his extraordinary energy, did exactly that in the two years that followed. At the end of the war, he was Britain's chief delegate to the Paris Peace Conference at which the Versailles Treaty was drafted. As a boy on school trips, Reginald’s son Paul proudly sang, along with his friends, Lloyd George knew my father; father knew Lloyd George - as it was true. Left: Charles Morley (courtesy Wikipedia) |

The Incident at Ashley

The dramatic incident, referred to above, happened during the First World War. In his job as trusted agent for the Morley family, Reginald acted as ‘go-between’ for his employer and the Morley tenants.

The dramatic incident, referred to above, happened during the First World War. In his job as trusted agent for the Morley family, Reginald acted as ‘go-between’ for his employer and the Morley tenants.

|

By this time, he may have felt that he fitted into Box society, being a local church organist, playing cricket and chess and enjoying a round of golf with friends and with Arnie, who was elected as a member of The Kingsdown Golf Club in 1905.

When the First World War broke out Reginald was aged 37 and probably thought he was too old for active service. But the war dragged on and in May 1916 military service was extended to married men aged between 18 and 41. At this time a few ladies accused him – now approaching 39 - of cowardice for not volunteering, and he was sent three white feathers anonymously. Right: Reginald about to putt a golf ball, possibly at Kingsdown |

Reginald was mortified that he should be thought of as unpatriotic by his neighbours, however few. For a number of years he had been heavily involved in local life partly through his role as organist and choirmaster at Monkton Farleigh Church, around which quite a bit of the family’s social life seems to have revolved as evidenced by letters from the Rector, the Rev. Selwyn Townshend.

He also had many friends in and around Box, including the Mullins family of Ashley. Bill Mullins, a water diviner and the brother of John Mullins, from Bath who wrote The Divining Rod: Its History, Truthfulness and Practical Utility, was a member of the choir at Monkton Farleigh. It seems that Reginald and later, son Paul, kept in touch with Bill and his wife, and usually called in on them at their cottage Ailsa Craig whenever they were in the area.

Faced with the hostility of some of his neighbours, Reginald discussed volunteering with his employer. In spite of the possibility of having no job waiting for him at the end of the war, he joined up as a Private in the Welsh Regiment, based in Brecon, Charles Morley’s former constituency. However, he kept in touch with Charles and later correspondence shows that the two remained on good terms. Charles died in October 1917, leaving Reginald a small bequest in his will.

He also had many friends in and around Box, including the Mullins family of Ashley. Bill Mullins, a water diviner and the brother of John Mullins, from Bath who wrote The Divining Rod: Its History, Truthfulness and Practical Utility, was a member of the choir at Monkton Farleigh. It seems that Reginald and later, son Paul, kept in touch with Bill and his wife, and usually called in on them at their cottage Ailsa Craig whenever they were in the area.

Faced with the hostility of some of his neighbours, Reginald discussed volunteering with his employer. In spite of the possibility of having no job waiting for him at the end of the war, he joined up as a Private in the Welsh Regiment, based in Brecon, Charles Morley’s former constituency. However, he kept in touch with Charles and later correspondence shows that the two remained on good terms. Charles died in October 1917, leaving Reginald a small bequest in his will.

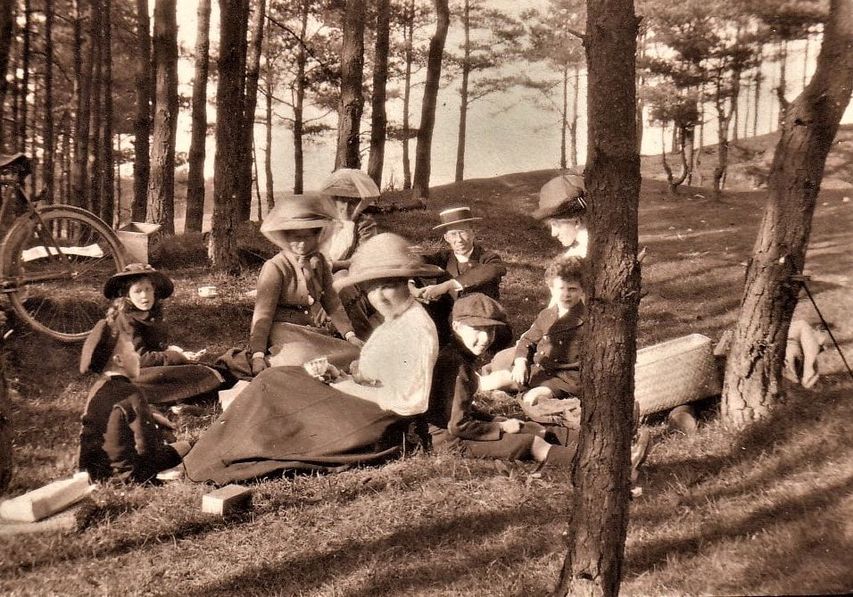

The photo above is of a picnic outing at Kingsdown in about 1912. Arnie and son Paul, the small boy with curly hair, are on the far right. The other people in the picture are unknown, but perhaps were local Box residents. Does anyone recognise the man with the distinctive glasses and/or the other children and adults?

After Reginald's treatment and now on her own with a small child, Arnie felt that she couldn't remain in Ashley and moved back to be with her family in Exeter where she volunteered for nursing in the war hospitals there. She turned up for her first day at work expecting to be carrying out general nursing duties only to find herself immediately promoted to the rank of sister, presumably because qualified nurses were a bit of a rarity in those circumstances. It was at least twelve years since she had done any nursing and found the unexpected responsibility rather stressful. It is likely that she also had charge of the VADs (Voluntary Aid Detachment of Nurses) which must have been quite a challenge in itself.

Reginald and Arnie After Box

By late 1916, Reginald had been appointed to the Officers Cadet Battalion, based in Cambridge where, Charles Morley notes, he will have enjoyed the sung services at King’s Chapel. This was borne out by a postcard of the interior of King’s Chapel Reginald sent Arnie on which he referred to the ‘gorgeously beautiful service’ held there. While in Cambridge, he worried about his ability to ‘pass out’ of training, however, The London Gazette for 10 April 1917 records, under the heading Welsh R(egiment): Cadet Reginald Horace Botcherby to be temporary 2nd Lieutenant from 1 March 1917.[4]

His military service record is still not available at Somerset House but we know that he served in France, based in or around a Cathedral City which could have been Rouen, judging by the postcards he sent home to his family.

By late 1916, Reginald had been appointed to the Officers Cadet Battalion, based in Cambridge where, Charles Morley notes, he will have enjoyed the sung services at King’s Chapel. This was borne out by a postcard of the interior of King’s Chapel Reginald sent Arnie on which he referred to the ‘gorgeously beautiful service’ held there. While in Cambridge, he worried about his ability to ‘pass out’ of training, however, The London Gazette for 10 April 1917 records, under the heading Welsh R(egiment): Cadet Reginald Horace Botcherby to be temporary 2nd Lieutenant from 1 March 1917.[4]

His military service record is still not available at Somerset House but we know that he served in France, based in or around a Cathedral City which could have been Rouen, judging by the postcards he sent home to his family.

|

He was wounded in the side by a machine gun bullet on 25 March 1918 during the German spring offensive, codenamed Operation Michael, which had begun on 21 March, and his name was included in the list of wounded officers issued by the War Office for 13 April 1918.[5]

He had written to Arnie on 20th March, but she had heard nothing from him once the offensive was under way. From her daily letters to him from the 22nd March onwards she grew ever more anxious, especially after the 24th when she first became aware of the German attack. She wrote, on the 25th March I do indeed hope I shall get some news of you very soon as the suspense is simply horrible, and the disappointment as each post goes by, sickening. I cannot write of other things until I know you are safe. At last, on the 30th, she received a wire to say he had been wounded by a machine gun bullet, but at least still alive. She wrote You do not know what it means to me not to be able to be with you – me, a nurse, too. Reginald was stretchered back to hospital in Brighton, recovered and continued to work for the military after World War 1, firstly in Sheffield, which had become the centre of a large munitions industry, and later in the Woolwich area of London until around the 1930s. By then, the opportunities for men like him would have been severely restricted because of his age and the decline of the landed gentry who might have employed him for his experience. |

By the early 1930s, Arnie and Reginald were living in Eltham where Arnie died in 1934. The 1939 Register shows Reginald in Hampstead with his brother Percy, also now a widower. He later moved to the Lancaster Gate area to be with his son, Paul, by then a civil engineer working for the Air Ministry in a reserved occupation. From correspondence dated December 1940, he is known to have stayed with Mrs Ruth Morley (Charles’s daughter-in-law) at Ashley Wood, Kingsdown, together with Paul and daughter-in-law, Helen. He died in London in 1945, having remained in contact with the Morley family until his death.

We would hope that white feather incidents might never recur, but there are examples of it again during the Second World War. Nowadays, rising levels of income and education and a peaceful domestic society has enabled many of us to enjoy a comfortable middle-class lifestyle. Reginald and Arnie lived from the High Victorian through to the inter-war years. In terms of their lifestyle, employment and ethics they anticipated a more modern society, more like us than some Box villagers in 1916.

We would hope that white feather incidents might never recur, but there are examples of it again during the Second World War. Nowadays, rising levels of income and education and a peaceful domestic society has enabled many of us to enjoy a comfortable middle-class lifestyle. Reginald and Arnie lived from the High Victorian through to the inter-war years. In terms of their lifestyle, employment and ethics they anticipated a more modern society, more like us than some Box villagers in 1916.

References

[1] Hampstead and Highgate Express, 16 May 1896 and 9 June 1894

[2] Parish Magazine, August 1903

[3] See https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/I._and_R._Morley

[4] The London Gazette, 10 April 1917

[5] Weekly Casualty List, 1 January 1918 and The Western Morning News, 16 April 1918

[1] Hampstead and Highgate Express, 16 May 1896 and 9 June 1894

[2] Parish Magazine, August 1903

[3] See https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/I._and_R._Morley

[4] The London Gazette, 10 April 1917

[5] Weekly Casualty List, 1 January 1918 and The Western Morning News, 16 April 1918