|

Bath Blitz April 1942

Photos courtesy Eric Callaway March 2018 In October 1941, the County Council designated Box Village as an Emergency Feeding and Rest Centre to take three hundred evacuees from Bath or Bristol, in the event of a sustained blitz there.[1] Local administration was organised by Miss Janet Morrice, Mr Wilkinson and vicar Arthur Maltin. The Day Schools, the Methodist Chapel Schools, the Bingham Hall, and the skittle alley of the Lamb Inn were named as assembly points for those seeking refuge. Mattresses, blankets, tinned food and emergency commodities were stored in the locked classroom, formerly the Infants Department at the school. |

Janice Cannings Remembers a Homeless Man

I remember the time that Bath was bombed when I was a young child. The next morning my mother went to the outshed near our home at Pye Corner to collect coal to light the fire to keep us four children warm (no central heating in those days). In the outshed was an old settee which my parents had discarded. Mum discovered a man who had been sleeping there overnight. He said he had walked from Bath to get away from the bombing and was trying to make his way up to London to see if his parents were still alive. My mother brought him into the kitchen and made him a hot cup of tea. She gave him a breakfast of eggs and bacon and he said he could not remember having such wonderful meal.

Due to the rationing in the war, the food was unusual but my dad kept chicken, ducks, geese and pigs. Being a country man, he would kill a pig so we could have bacon, pork and ham. He also had three greenhouses and about 100 plum trees. He worked very hard digging the land to keep all that going, as well as doing his daytime railway inspector's job. I have recently read in the paper that they have discovered the inside of a pig is similar to a human being. My old dad could have told them that in 1942.

I remember the time that Bath was bombed when I was a young child. The next morning my mother went to the outshed near our home at Pye Corner to collect coal to light the fire to keep us four children warm (no central heating in those days). In the outshed was an old settee which my parents had discarded. Mum discovered a man who had been sleeping there overnight. He said he had walked from Bath to get away from the bombing and was trying to make his way up to London to see if his parents were still alive. My mother brought him into the kitchen and made him a hot cup of tea. She gave him a breakfast of eggs and bacon and he said he could not remember having such wonderful meal.

Due to the rationing in the war, the food was unusual but my dad kept chicken, ducks, geese and pigs. Being a country man, he would kill a pig so we could have bacon, pork and ham. He also had three greenhouses and about 100 plum trees. He worked very hard digging the land to keep all that going, as well as doing his daytime railway inspector's job. I have recently read in the paper that they have discovered the inside of a pig is similar to a human being. My old dad could have told them that in 1942.

Bath Blitz, 23 April 1942

By February 1942 it was apparent that an assault on Bath was imminent and a major civil defence exercise was undertaken on the new hospital site in the centre of the city with simulations of burning buildings, live incendiary bombs, and how an anti-gas treatment house would be used in the event of a gas attack.[2]

The Box Rest Centre was opened in emergency conditions on Sunday 20 April 1942 following the bombing of Bath the previous night. Thirteen persons were received the first night, then a further 100 rising by some estimates to 200 people.[3] But the real attack, the Baedeker Raid, came on 23 April 1942. The city was shocked at the severity and the newspaper wrote about it in graphic terms, When the Hun raiders rained their death bombs on Bath on Sunday night.[4] People were being pulled out of the wreckage still alive three days later, many whole families perished when their house collapsed on top of them and their indoor Morrison Shelter was inadequate to protect them. The elderly had to be physically carried out of the wreckage of their homes.[5] Dr Mary Middlemass, the doctor for ByBrook House Waifs and Strays Home in Middlehill, was killed when a bomb landed directly on her house.

By February 1942 it was apparent that an assault on Bath was imminent and a major civil defence exercise was undertaken on the new hospital site in the centre of the city with simulations of burning buildings, live incendiary bombs, and how an anti-gas treatment house would be used in the event of a gas attack.[2]

The Box Rest Centre was opened in emergency conditions on Sunday 20 April 1942 following the bombing of Bath the previous night. Thirteen persons were received the first night, then a further 100 rising by some estimates to 200 people.[3] But the real attack, the Baedeker Raid, came on 23 April 1942. The city was shocked at the severity and the newspaper wrote about it in graphic terms, When the Hun raiders rained their death bombs on Bath on Sunday night.[4] People were being pulled out of the wreckage still alive three days later, many whole families perished when their house collapsed on top of them and their indoor Morrison Shelter was inadequate to protect them. The elderly had to be physically carried out of the wreckage of their homes.[5] Dr Mary Middlemass, the doctor for ByBrook House Waifs and Strays Home in Middlehill, was killed when a bomb landed directly on her house.

The bombing continued on 25 April and encompassed railway tracks, road movement and again the civilian population.[6] The government was keen to keep up morale and reports appeared in the newspapers about how Henrietta Park took the worst of the damage, destroying park railings, trees and the shrubbery but not a delightful little enclosure with lily pond and rosery.[7] Of course, it was pure propaganda for the consumption of scared residents but it fooled no one because they could see the residential destruction and the hits on many large buildings including the Council Offices, Holy Trinity Church and the Abbey area, where Abbey Church House was hit in one of the first attacks.[8]

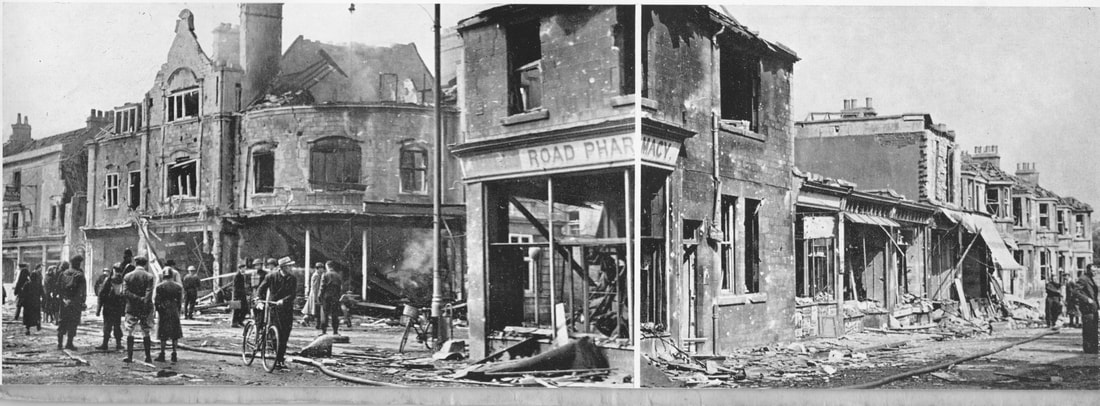

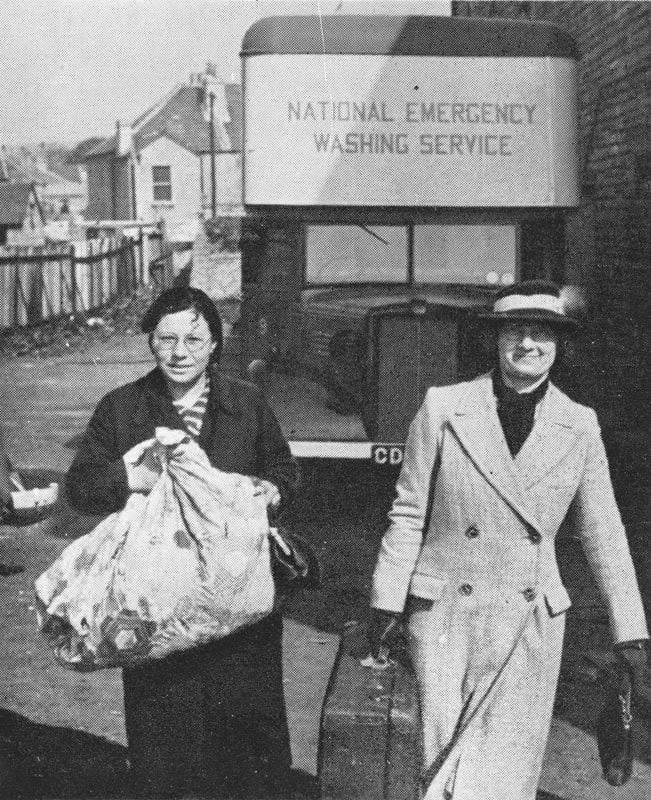

The public attitude to the Bath Blitz was truly remarkable. The photos above were published by The Bath and Wilts Chronicle and Herald capturing a record of bombed buildings and wartime emergency feeding stations. It was utter defiance and quite unlike the strict control exercise by the government over most bad news. (All photos courtesy Eric Callaway).

Eddie Weeks' Memories

I found the Home Guard photo in your last issue was very interesting as my father's cousin is in the back row. He and his wife were bombed out in Bath and lived with us for a while before moving to a cottage on a farm in Middlehill. Also in the front row squatting down I think is Kruger Barnett whom I remember keeping all the verges, drains and ditches in good order in Ashley.

I was told that he was nicknamed Kruger because he had served in the Boer War.

I found the Home Guard photo in your last issue was very interesting as my father's cousin is in the back row. He and his wife were bombed out in Bath and lived with us for a while before moving to a cottage on a farm in Middlehill. Also in the front row squatting down I think is Kruger Barnett whom I remember keeping all the verges, drains and ditches in good order in Ashley.

I was told that he was nicknamed Kruger because he had served in the Boer War.

Even the tragedy of hardship and death caused by the bombing was recorded.

Bill Cooper Remembers the Bombing

When Bath was blitzed, it was ironic that my aunty Dot, an Air Raid Warden in badly blitzed Portsmouth, had been staying with us for a few days. She had come to our house in Chapel Lane to get away from the nightly raids. The bomb that landed at the end of Manvers Street took out all the glass covering the Bath Railway Station platforms, meaning that the station was temporarily

un-usable. All rail traffic had to use Bathampton as the main station for a few days. Luckily, the tracks were untouched.

Afterwards my aunt was pleased to be going back to Portsmouth which was very well defended. She missed the reassuring sound of home guns retaliating. Here there was virtually no defence.

After the first night's blitz, a family friend from Forester Avenue, Bath, called to say she was bringing the occupants of three flats to stay as they were all damaged and uninhabitable . There were 15 people in all in addition to our family of four. The Bath families had to be dispersed around friends in village. I had to sleep on a camp bed surrounded by the rest of the family and the Bingham Hall ceased to be a canteen, temporarily becoming a rest centre.

One of my lasting memories is my father arriving with a colleague from work in Bath, who had returned home from night duty to find his home in Oldfield Park flattened. He had nowhere to stay and was desperately searching for his wife. It turned out that she had been killed. Apparently, all the deceased were collected by the authorities and laid out in a warehouse somewhere in Twerton. Later he found her body.

When Bath was blitzed, it was ironic that my aunty Dot, an Air Raid Warden in badly blitzed Portsmouth, had been staying with us for a few days. She had come to our house in Chapel Lane to get away from the nightly raids. The bomb that landed at the end of Manvers Street took out all the glass covering the Bath Railway Station platforms, meaning that the station was temporarily

un-usable. All rail traffic had to use Bathampton as the main station for a few days. Luckily, the tracks were untouched.

Afterwards my aunt was pleased to be going back to Portsmouth which was very well defended. She missed the reassuring sound of home guns retaliating. Here there was virtually no defence.

After the first night's blitz, a family friend from Forester Avenue, Bath, called to say she was bringing the occupants of three flats to stay as they were all damaged and uninhabitable . There were 15 people in all in addition to our family of four. The Bath families had to be dispersed around friends in village. I had to sleep on a camp bed surrounded by the rest of the family and the Bingham Hall ceased to be a canteen, temporarily becoming a rest centre.

One of my lasting memories is my father arriving with a colleague from work in Bath, who had returned home from night duty to find his home in Oldfield Park flattened. He had nowhere to stay and was desperately searching for his wife. It turned out that she had been killed. Apparently, all the deceased were collected by the authorities and laid out in a warehouse somewhere in Twerton. Later he found her body.

References

[1] Parish Magazine, October 1941

[2] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 21 February 1942

[3] Parish Magazine, June 1942

[4] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 2 May 1942

[5] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 24 December 1942

[6] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 6 June 1942

[7] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 20 June 1942

[8] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 28 November 1942, 24 December 1942 and 10 April 1943

[1] Parish Magazine, October 1941

[2] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 21 February 1942

[3] Parish Magazine, June 1942

[4] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 2 May 1942

[5] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 24 December 1942

[6] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 6 June 1942

[7] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 20 June 1942

[8] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 28 November 1942, 24 December 1942 and 10 April 1943