AT WAR 11am 3 September 1939 Clive Banks and his cousin Sally Hicks February 2017

|

Recalling the Moment It was a pleasant late summer morning in 1939 when my cousin Sally, aged 9 years, attended the Sunday morning service at St Thomas à Becket Church. She was accompanied by her grandmother, Mabel Vezey, (who was also my great aunt) and Doctor Martin. He had apparently been quite sweet on the long-widowed Mabel for many years but his regard for her was never reciprocated in the way that he had hoped. They all sat in their usual pews in the back row of the front block facing the lectern, with Sally sitting between them. My great uncle, Harry Milsom, was in the choir. There was a good attendance at that time and the church was fairly full. |

Sally then recalls the moment when the vicar, Arthur Maltin, approached the chancel steps and standing there, made the announcement that we were now at war with Germany. It must have been one of the most dramatic moments in the several-hundred year history of Box Church.

The usual time for the start of morning service was 11am, precisely the time when the ultimatum to Germany was due to expire. The radio broadcast by the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, announcing the declaration of war did not take place until 11.15am, so the vicar would not of been aware of the situation until then. Sally does not remember when the service started; she just remembered sitting there waiting. It seems probable that the start of the service was delayed to await the news. I like to think that the Rev Maltin had been listening to a radio in the vestry at low volume. One can imagine the tension amongst the congregation, who would probably have guessed the reason for the delay. Most of them would have lived through the horrors of the previous Great War, which was supposed to have been the War to End War. Sally, now Dr Sally Hicks, must be one of the last survivors of that moment who was then old enough to realise its significance.

The usual time for the start of morning service was 11am, precisely the time when the ultimatum to Germany was due to expire. The radio broadcast by the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, announcing the declaration of war did not take place until 11.15am, so the vicar would not of been aware of the situation until then. Sally does not remember when the service started; she just remembered sitting there waiting. It seems probable that the start of the service was delayed to await the news. I like to think that the Rev Maltin had been listening to a radio in the vestry at low volume. One can imagine the tension amongst the congregation, who would probably have guessed the reason for the delay. Most of them would have lived through the horrors of the previous Great War, which was supposed to have been the War to End War. Sally, now Dr Sally Hicks, must be one of the last survivors of that moment who was then old enough to realise its significance.

Reaction in Box

The bells which were rung for this morning service were some of the last bells rung for the next three years until October 1942. By government order on 13 June 1940 bells were only to be used in emergency, which everyone knew to be the warning that the Germans had invaded Britain. Rev Arthur Maltin expressed the tragedy of warfare in his commentary three months after the outbreak: We commenced the year 1939 with high hopes for the future. Prosperity was on the up-grade, unemployment was decreasing ... We end 1939 at War... Our peoples have resolved to stand by certain principles of civilisation or perish.[1]

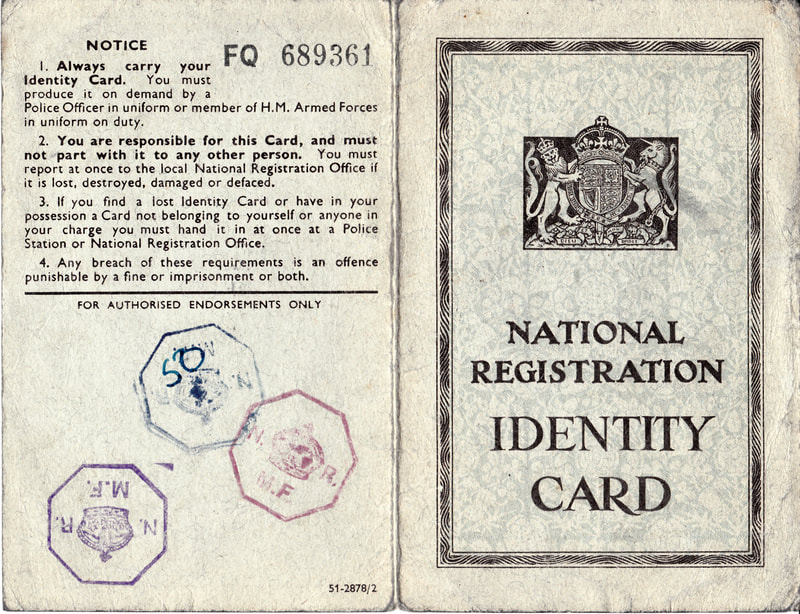

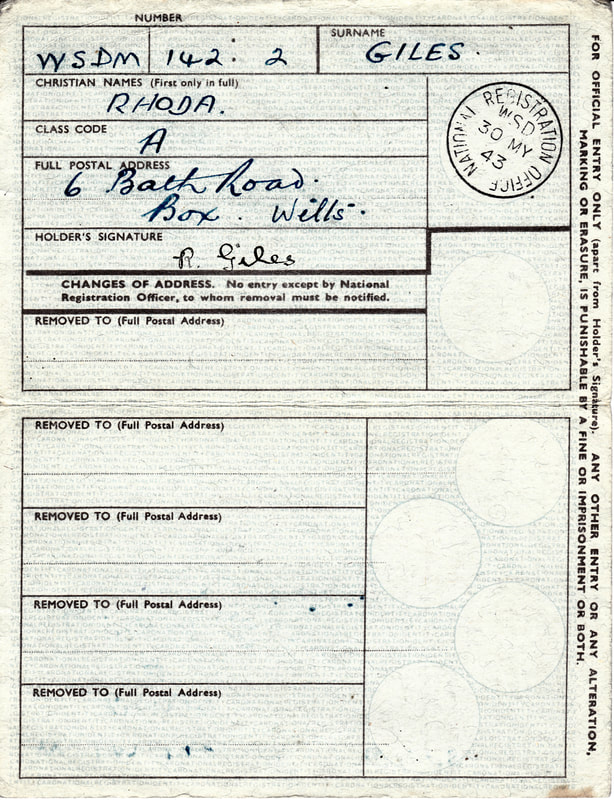

Preparations for war continued throughout 1939. Conscription was extended to men aged 18-41 and on 7 September Identity Cards were introduced. Box prepared for bloodshed, We have formed a Blood Transfusion Group in Box and about thirty people have given. Mrs Rooke, of Ben Mead, is kindly acting as secretary.[2]

The bells which were rung for this morning service were some of the last bells rung for the next three years until October 1942. By government order on 13 June 1940 bells were only to be used in emergency, which everyone knew to be the warning that the Germans had invaded Britain. Rev Arthur Maltin expressed the tragedy of warfare in his commentary three months after the outbreak: We commenced the year 1939 with high hopes for the future. Prosperity was on the up-grade, unemployment was decreasing ... We end 1939 at War... Our peoples have resolved to stand by certain principles of civilisation or perish.[1]

Preparations for war continued throughout 1939. Conscription was extended to men aged 18-41 and on 7 September Identity Cards were introduced. Box prepared for bloodshed, We have formed a Blood Transfusion Group in Box and about thirty people have given. Mrs Rooke, of Ben Mead, is kindly acting as secretary.[2]

Blackouts

One of the most disruptive aspects of village life was the blackout of all light on roads and domestic and factory buildings during pre-set hours of night-time. It made curfews almost inevitable and curtailed evening activities and travel. The blackout hours varied daily according to daylight times, so that in the spring time blackouts from 7.30pm to 7am was common.

The purpose of the blackout was to avoid assisting enemy bombers. Street lights were turned off, speed limits imposed of

20 miles per hour and white lines painted in the middle of roads but there were many crashes and fatalities. By October 1939, the Bath coroner advised motorists to avoid driving during blackout hours. Mr Charles Pearce, a retired gardener, had been knocked down by a car at 10pm on 17 October on the Devizes Road, 20 yards from his home, because it was difficult for the motorist to follow the white line and to see what was on the road in front.[3]

No-one was exempt from the restrictions, as Rev Maltin found out in May 1940. He had parked outside the Theatre Royal, Bath, during the daylight hours to attend a meeting about the Actors' Church Union.[4] Unfortunately he stayed beyond the watershed and the police found that he had parked on the wrong side of the road during blackout hours, suffering a 5s fine.

One of the most disruptive aspects of village life was the blackout of all light on roads and domestic and factory buildings during pre-set hours of night-time. It made curfews almost inevitable and curtailed evening activities and travel. The blackout hours varied daily according to daylight times, so that in the spring time blackouts from 7.30pm to 7am was common.

The purpose of the blackout was to avoid assisting enemy bombers. Street lights were turned off, speed limits imposed of

20 miles per hour and white lines painted in the middle of roads but there were many crashes and fatalities. By October 1939, the Bath coroner advised motorists to avoid driving during blackout hours. Mr Charles Pearce, a retired gardener, had been knocked down by a car at 10pm on 17 October on the Devizes Road, 20 yards from his home, because it was difficult for the motorist to follow the white line and to see what was on the road in front.[3]

No-one was exempt from the restrictions, as Rev Maltin found out in May 1940. He had parked outside the Theatre Royal, Bath, during the daylight hours to attend a meeting about the Actors' Church Union.[4] Unfortunately he stayed beyond the watershed and the police found that he had parked on the wrong side of the road during blackout hours, suffering a 5s fine.

First Box Group Gang Show November 1939. Back Row L to R: Alan Sheppard, Phil Lambert, Chris Sparrow, Gordon McTaggart, unknown, Phil McTaggart, Mervyn Gregory, Jim Browning, Nigel Bence, Peter Armstead, Geoff Bence, unknown, unknown. Middle Row: Hubert Wickings, four unknown, John Miller, Len Weekes, six unknown. Front Row: nine unknown, Bryan Bence and four unknown (courtesy Margaret Wakefield)

The Phoney War

Notwithstanding all the preparations, Box continued untroubled during the period of the so-called phoney war. Germany occupied Poland, then attacked Denmark and Norway but Britain was not involved in any significant military action. The scouts and cubs in the 1939 Christmas Gang Show enjoyed the moment of quiet but many would be called up to serve their country before the war was over. [Please let us know if you can identify any of the missing names above.]

The phoney war came to an end in May 1940 when Hitler invaded France, Holland, Luxembourg and Belgium. The speed of German success amazed people and everyone knew the implications of Churchill replacing Chamberlain as Prime Minister and his speech that, in later times, history would recall the part of Britain and the Empire in the coming war That this was their finest hour.

Notwithstanding all the preparations, Box continued untroubled during the period of the so-called phoney war. Germany occupied Poland, then attacked Denmark and Norway but Britain was not involved in any significant military action. The scouts and cubs in the 1939 Christmas Gang Show enjoyed the moment of quiet but many would be called up to serve their country before the war was over. [Please let us know if you can identify any of the missing names above.]

The phoney war came to an end in May 1940 when Hitler invaded France, Holland, Luxembourg and Belgium. The speed of German success amazed people and everyone knew the implications of Churchill replacing Chamberlain as Prime Minister and his speech that, in later times, history would recall the part of Britain and the Empire in the coming war That this was their finest hour.

References

[1] Parish Magazine, January 1940

[2] Parish Magazine, December 1939

[3] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 26 October 1939

[4] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 25 May 1940

[1] Parish Magazine, January 1940

[2] Parish Magazine, December 1939

[3] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 26 October 1939

[4] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 25 May 1940