Ashley Firing Range Suggested by Roger Oliver & Stephen Eyles, November 2023

Origin of the Box Range

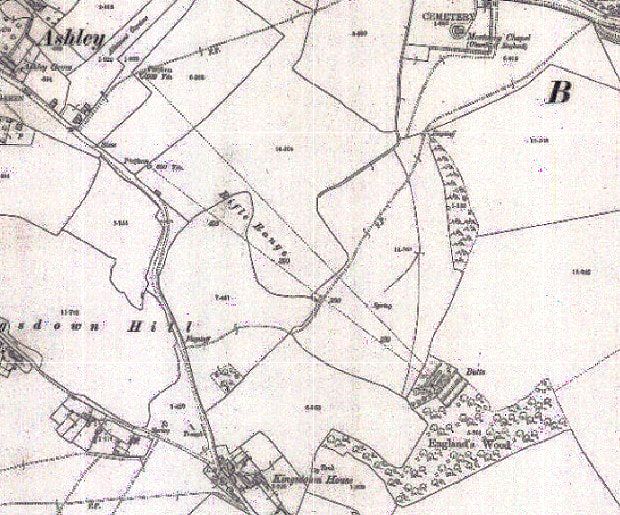

The Outdoor Firing Range went from Ashley going eastwards towards and north of the cemetery. It was started before the Second Boer War 1899-1902, possibly in the decades after the 1860s when the National Rifle Association was formed.[1]

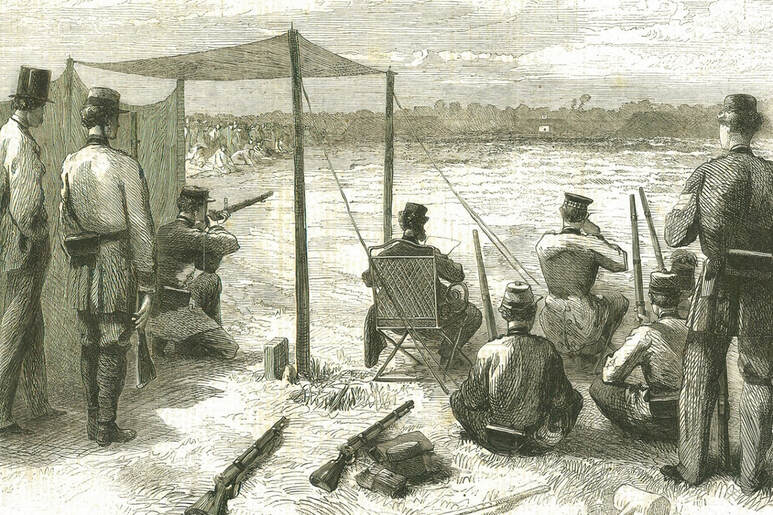

The Box range became an event as much as a military exercise. There was a series of shooting competitions for prizes competed for by servicemen and officers which became an annual gathering every summertime. Each competition was named, the winners receiving a plate trophy and men in the ranks getting cash prizes. There was a huge variety of shots including competitions covering a range of distances, kneeling or Queen’s position (so called because Queen Victoria made the first shot at the inaugural Rifle Association meeting), individual and different numbers per team and omnium competitions.[2]

A firing range had been used at Bedminster for the Somerset Volunteers and the North Somerset Imperial Yeomanry but it was more convenient to have military horse exercises on Kingsdown Common associated with shooting practice at Ashley.[3]

The Ashley area was better than Kingsdown for shooting contests as it was less windy and less prone to mist. The event became a series of contests for teams from battalions all over Somerset although, when the Box range was temporarily closed in 1928,

it moved back to Bedminster.[4]

The Outdoor Firing Range went from Ashley going eastwards towards and north of the cemetery. It was started before the Second Boer War 1899-1902, possibly in the decades after the 1860s when the National Rifle Association was formed.[1]

The Box range became an event as much as a military exercise. There was a series of shooting competitions for prizes competed for by servicemen and officers which became an annual gathering every summertime. Each competition was named, the winners receiving a plate trophy and men in the ranks getting cash prizes. There was a huge variety of shots including competitions covering a range of distances, kneeling or Queen’s position (so called because Queen Victoria made the first shot at the inaugural Rifle Association meeting), individual and different numbers per team and omnium competitions.[2]

A firing range had been used at Bedminster for the Somerset Volunteers and the North Somerset Imperial Yeomanry but it was more convenient to have military horse exercises on Kingsdown Common associated with shooting practice at Ashley.[3]

The Ashley area was better than Kingsdown for shooting contests as it was less windy and less prone to mist. The event became a series of contests for teams from battalions all over Somerset although, when the Box range was temporarily closed in 1928,

it moved back to Bedminster.[4]

There is still evidence of the range in the footings of the butts in the fields and number 4 Wilton Cottages was later named Range View recalling that it overlooked the targets. Over the years, the range was used by several different military services including the North Somerset Yeomanry, the Somerset Territorial Volunteers and the Second World War Home Guard.[5]

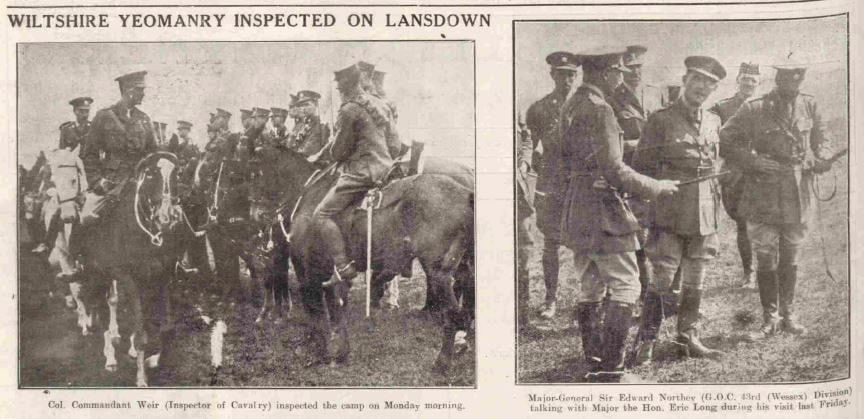

Somerset Territorials

Although the Somerset Light Infantry held annual camps in Box at Kingsdown and Ashley, these didn’t involve Box servicemen because these were recruited into the Wiltshire Yeomanry and Volunteers. Nonetheless the Somerset regiments started to use the Box areas to practice manoeuvres starting in the years before the First World War. It was a difficult terrain, involving the import of food, water, fuel, straw and animal provisions with tenders invited from local suppliers.[6] The meetings weren’t purely manoeuvres but also had a social aspect with promotions announced and medals awarded, such as in 1901 when Boer War medals were awarded to men in the North Somerset Imperial Yeomanry, 48th Company by the Earl of Cork.[7] Less enjoyable were night-time manoeuvres and the trumpet voluntary to raise men from their slumbers on the last night after 20 days encampment for a simulated night fire alarm in 1900.[8]

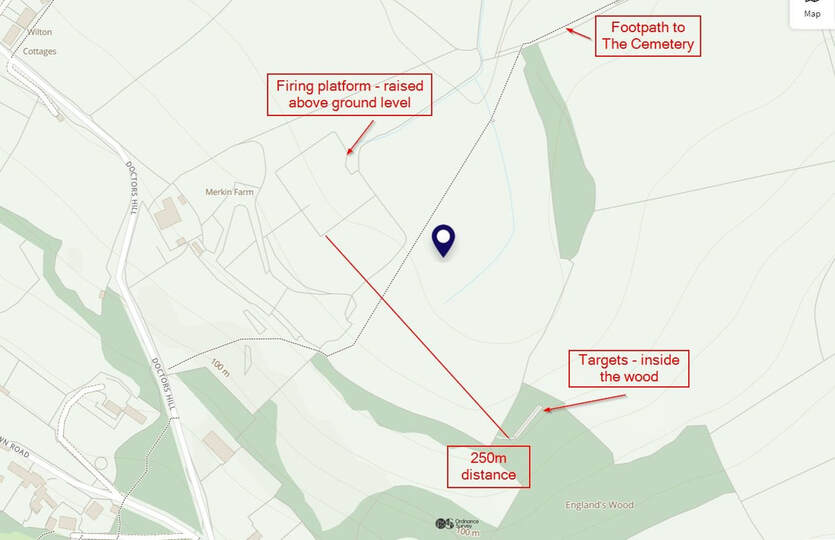

The Kingsdown camps were operated in association with the Ashley firing range so that men could practice shooting with live ammunition. A series of butts (derived from the archery term) was established at different distances down the valley to allow the men to experience a range of shots from Doctors Hill towards the area where Littlemead has now been built.

Somerset Territorials

Although the Somerset Light Infantry held annual camps in Box at Kingsdown and Ashley, these didn’t involve Box servicemen because these were recruited into the Wiltshire Yeomanry and Volunteers. Nonetheless the Somerset regiments started to use the Box areas to practice manoeuvres starting in the years before the First World War. It was a difficult terrain, involving the import of food, water, fuel, straw and animal provisions with tenders invited from local suppliers.[6] The meetings weren’t purely manoeuvres but also had a social aspect with promotions announced and medals awarded, such as in 1901 when Boer War medals were awarded to men in the North Somerset Imperial Yeomanry, 48th Company by the Earl of Cork.[7] Less enjoyable were night-time manoeuvres and the trumpet voluntary to raise men from their slumbers on the last night after 20 days encampment for a simulated night fire alarm in 1900.[8]

The Kingsdown camps were operated in association with the Ashley firing range so that men could practice shooting with live ammunition. A series of butts (derived from the archery term) was established at different distances down the valley to allow the men to experience a range of shots from Doctors Hill towards the area where Littlemead has now been built.

Activities at Camp

An extensive report was given about the training undertaken by the Somerset Yeomanry in 1901.[9] The assembly comprised 327 men divided into 3 squadrons. There were 16 officers, 18 sergeants, 21 corporals, 6 trumpeters and 266 troopers. Included in the numbers were 19 musicians. Many men that year had served in the Boer War and one suffered a recurrence of sunstroke at Kingsdown which he had contracted in South Africa. Interestingly, most of these people were middleclass members of society who had to buy their own uniforms and rifles.

Activities that year included equipment cleaning and grooming the horses (assisted by 30 non-service grooms), endless parading and assembling in formation, and Church services in Bath Abbey each Sunday. More practical instruction was given on handling rifles, and scouting work involved reconnaissance outside the camp to thwart role-playing agitators at Atworth, Melksham, Farleigh Wick, Bradford Leigh and Chalfield. In the pouring rain some men marched to the Ashley firing range for practice and the annual competition; others practiced flag signalling. And so it went on for 20 days with one day off for men to go back to their business duties.

Undoubtedly, the meeting improved the morale of participants (and also the observers from the Kingsdown sheep fair which was happening at the same time). A regimental sports day attracted much attention with the usual egg and spoon races, cycle chases and tug-of-war. A new event, pillow fights on a slippery pole, provided generous amusement. Comradeship was generated by the band playing for two hours every afternoon but the event was also hard work with Kingsdown Hill being rechristened Spion Kop and the arduous task of a full-dress march into Bath, parade around the city and a long salute and address outside the Guildhall attended by the mayor and civic dignitaries.

An extensive report was given about the training undertaken by the Somerset Yeomanry in 1901.[9] The assembly comprised 327 men divided into 3 squadrons. There were 16 officers, 18 sergeants, 21 corporals, 6 trumpeters and 266 troopers. Included in the numbers were 19 musicians. Many men that year had served in the Boer War and one suffered a recurrence of sunstroke at Kingsdown which he had contracted in South Africa. Interestingly, most of these people were middleclass members of society who had to buy their own uniforms and rifles.

Activities that year included equipment cleaning and grooming the horses (assisted by 30 non-service grooms), endless parading and assembling in formation, and Church services in Bath Abbey each Sunday. More practical instruction was given on handling rifles, and scouting work involved reconnaissance outside the camp to thwart role-playing agitators at Atworth, Melksham, Farleigh Wick, Bradford Leigh and Chalfield. In the pouring rain some men marched to the Ashley firing range for practice and the annual competition; others practiced flag signalling. And so it went on for 20 days with one day off for men to go back to their business duties.

Undoubtedly, the meeting improved the morale of participants (and also the observers from the Kingsdown sheep fair which was happening at the same time). A regimental sports day attracted much attention with the usual egg and spoon races, cycle chases and tug-of-war. A new event, pillow fights on a slippery pole, provided generous amusement. Comradeship was generated by the band playing for two hours every afternoon but the event was also hard work with Kingsdown Hill being rechristened Spion Kop and the arduous task of a full-dress march into Bath, parade around the city and a long salute and address outside the Guildhall attended by the mayor and civic dignitaries.

Attitude of Residents

Clearly the invasion of Kingsdown by servicemen caused considerable disruption and the use of the Ashley firing range generated complaints that villagers were Under Fire from inaccurate firing by the Somerset Territorial Army at the Ashley range. In 1927 the Parish Council complained that stray bullets caused distress to Henley residents.[10]

A petition was started in September that year by the inhabitants of Henley and Longsplatt: There is seldom an occasion when firing is in progress that the people of this place are not terrified by stray bullets but the climax was reached last Saturday week when a succession of explosive bullets dropped, some of them within a few yards of men working in the harvest field at Henley.[11] One passed close to the face of a resident; another went through a front door.[12]

The direction of the 400- and 600-yard shoots is unclear as there seems to be insufficient space for them to follow the same line as the smaller shoots. The references to stray bullets seems to indicate some random lines.

Clearly the invasion of Kingsdown by servicemen caused considerable disruption and the use of the Ashley firing range generated complaints that villagers were Under Fire from inaccurate firing by the Somerset Territorial Army at the Ashley range. In 1927 the Parish Council complained that stray bullets caused distress to Henley residents.[10]

A petition was started in September that year by the inhabitants of Henley and Longsplatt: There is seldom an occasion when firing is in progress that the people of this place are not terrified by stray bullets but the climax was reached last Saturday week when a succession of explosive bullets dropped, some of them within a few yards of men working in the harvest field at Henley.[11] One passed close to the face of a resident; another went through a front door.[12]

The direction of the 400- and 600-yard shoots is unclear as there seems to be insufficient space for them to follow the same line as the smaller shoots. The references to stray bullets seems to indicate some random lines.

Later History: Roger Oliver

In the 1950s I was stationed at Basil Hill Barracks, Hawthorn, on my regular army service duty. We regularly went to the Ministry of Defence 200-yard range at Ashley to practise 0.303-inch rifle shooting. I was in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) attached to the Ordnance Depot of the (Royal Army Ordnance Corps) RAOV in 1956-57.

Entrance to the range was at the bottom of Doctors Hill, where the road bends and widens. You went straight in at the 200-yard firing point, which was partially covered with a roof on legs. The 100-yard firing point was further down the hill, just an open-air mound. There were other firing points at 500 and 600 yards. This range was difficult to operate as three footpaths came down across the line, one from the right down Doctors Hill; a second from Henley, straight in front of the targets; and the third on the left from the A4 above the cemetery. All three footpaths took walkers straight towards the target area. We had to put red flags out to warn people. We also had sentries at each point where the footpath met the range. Shooting often stopped until walkers were safely clear.

Shooting continued here until the 1960s when the land was restored as farmland. Charlie Poulsom and Bob Hancock farmed the area for many years. After this, troops had to go to Salisbury Plain to practise shooting with live ammunition.

In the 1950s I was stationed at Basil Hill Barracks, Hawthorn, on my regular army service duty. We regularly went to the Ministry of Defence 200-yard range at Ashley to practise 0.303-inch rifle shooting. I was in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) attached to the Ordnance Depot of the (Royal Army Ordnance Corps) RAOV in 1956-57.

Entrance to the range was at the bottom of Doctors Hill, where the road bends and widens. You went straight in at the 200-yard firing point, which was partially covered with a roof on legs. The 100-yard firing point was further down the hill, just an open-air mound. There were other firing points at 500 and 600 yards. This range was difficult to operate as three footpaths came down across the line, one from the right down Doctors Hill; a second from Henley, straight in front of the targets; and the third on the left from the A4 above the cemetery. All three footpaths took walkers straight towards the target area. We had to put red flags out to warn people. We also had sentries at each point where the footpath met the range. Shooting often stopped until walkers were safely clear.

Shooting continued here until the 1960s when the land was restored as farmland. Charlie Poulsom and Bob Hancock farmed the area for many years. After this, troops had to go to Salisbury Plain to practise shooting with live ammunition.

References

[1] The earliest reference appears to be pre-1899 The Bath Chronicle, 14 September 1899. See also English Rifles: The Victorian NRA | History Today

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 14 September 1899

[3] Shepton Mallett Journal, 27 September 1901

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 22 September 1928

[5] Courtesy Eric and Sandra Callaway

[6] The Wiltshire Times, 6 April 1912

[7] The Somerset Standard, 13 September 1901

[8] The Wells Journal, 27 September 1900 and The Wiltshire Times, 29 September 1900

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 26 and 29 September 1901 and 3 October 1901

[10] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 1 October 1927

[11] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 17 September 1927

[12] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 17 September 1927

[1] The earliest reference appears to be pre-1899 The Bath Chronicle, 14 September 1899. See also English Rifles: The Victorian NRA | History Today

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 14 September 1899

[3] Shepton Mallett Journal, 27 September 1901

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 22 September 1928

[5] Courtesy Eric and Sandra Callaway

[6] The Wiltshire Times, 6 April 1912

[7] The Somerset Standard, 13 September 1901

[8] The Wells Journal, 27 September 1900 and The Wiltshire Times, 29 September 1900

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 26 and 29 September 1901 and 3 October 1901

[10] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 1 October 1927

[11] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 17 September 1927

[12] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 17 September 1927