Ashley Manor House possibly rebuilt in 1604 (photo Box Parish Council)

Ashley Manor House possibly rebuilt in 1604 (photo Box Parish Council)

The History of Ashley

Paul Bazell asked us:

We would love to see anything to do with our house, Ashley Green, and the Ashley area in general.

We hope that Paul and everyone will enjoy our history of Ashley.

Please get in touch if you have more to add.

Alan Payne, February 2014

Paul Bazell asked us:

We would love to see anything to do with our house, Ashley Green, and the Ashley area in general.

We hope that Paul and everyone will enjoy our history of Ashley.

Please get in touch if you have more to add.

Alan Payne, February 2014

Early History

The earliest reference to Ashley is in the late 1100s when Robert de Mountfort of Ashley held land both there and at Walcot, Swindon. The origin of the name may be ash wood or clearing.[1] Another theory is that it described the ashlar Bath stone found in this area and is the reason for the economic success of the hamlet. The Mountfort family held these lands for over two centuries.[2]

The Mountforts may have resided at Ashley. One witness to the charters of Samson de Bigod refers to Robert de Muntford who in another charter is called Robert de Arselege.[3] The Mountforts lived there over a considerable period of time. In 1242 there is reference to Simon de Mountfort of Ashley; in 1340 John Mountfort of Ashley; and in 1428 another John Mountfort is mentioned.[4]

There are medieval references to other residents in the area, which was clearly a developed hamlet before the Black Death.[5] In 1336 William Poyntz of Ashley held land, and in 1346 there is a record of Jordan le Knyght of Aissheley.

The earliest reference to Ashley is in the late 1100s when Robert de Mountfort of Ashley held land both there and at Walcot, Swindon. The origin of the name may be ash wood or clearing.[1] Another theory is that it described the ashlar Bath stone found in this area and is the reason for the economic success of the hamlet. The Mountfort family held these lands for over two centuries.[2]

The Mountforts may have resided at Ashley. One witness to the charters of Samson de Bigod refers to Robert de Muntford who in another charter is called Robert de Arselege.[3] The Mountforts lived there over a considerable period of time. In 1242 there is reference to Simon de Mountfort of Ashley; in 1340 John Mountfort of Ashley; and in 1428 another John Mountfort is mentioned.[4]

There are medieval references to other residents in the area, which was clearly a developed hamlet before the Black Death.[5] In 1336 William Poyntz of Ashley held land, and in 1346 there is a record of Jordan le Knyght of Aissheley.

Depiction of medieval dairying

Depiction of medieval dairying

Medieval Dairying

It is possible that dairying was the reason for the wealth which existed at Ashley and which in 1306 gave rise to an intriguing legal reference: Roger Crede of Cosham, son of Walter de Cosham, for burgling Stephen de Aschlegh's house and taking goods to the value of 100s. This was a fortune, equivalent today to perhaps £40,000.[6]

Dairying was given further impetus after the Black Death when the shortage of manpower curtailed arable farming. The surnames Cottle (cattle) and Bollwell (bull), which occur in Box around 1600, hark back to dairy or beef grazing origins.[7]

Box was already characterised by small, enclosed pastoral fields for beef rearing, dairy cows, sheep and goats. After about 1500 cows previously kept as beef sucklers were turned to milk production and Wiltshire butter and cheese was sold in London and other towns.[8] The North Wiltshire dairy industry was a highly developed trade and a wide range of cattle were kept. A century later the local historian John Aubrey said: I have not seen so many pied cattle any where as in North Wiltshire. The county hereabout is much inclined to pied cattle, but commonly the colour is black, or brown, or deep red.[9]

A dairy farm called Weck Farm existed at Ashley. It had a cottage on the land and there was sufficient running water which was needed for cleaning down. The slurry would be used on the next door common field strips. The landlord retained the hay and pasture fields at Ashley (called Ha Grove and Broad Lay) and let out other fields for farming. Above Littlemead there is a property called The Barton, an old word for a farmyard where land had been enclosed to make small closes for cattle.[10] There are four other fields called weeke or wicke in the area, which are dairy farms but too small to be self-sufficient.

The size of medieval dairy herds was minute compared to modern herds. For example, at Whitely, Melksham in about 1550, a herd was recorded as 4 oxen, 5 kine (cows), 4 bullocks under 2 years and 5 yearlings. A wealthy Corsham farmer in 1666 had 7 plough oxen and 12 cows and steers.[11] Oxen were used for ploughing Wiltshire soils until about 1700.

Landlords rarely ran their own dairy operations, preferring instead to rent out pasture land and sell winter fodder to small family farms. This is the origin of the word farmer (where the landlord received a flat-rate fee in advance and allowed the tenant to make as much money as he could out of husbandry; similar to the farming of taxes)[11a]. The farmer in turn sub-contracted the milking work to dairymen by leasing out pregnant cows on an annual contract together with a house and sometimes a dairy. The dairyman earned his living from selling the milk, butter and cheese. Richard Crick in Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles was just such a dairyman and Tess worked as a milkmaid for him.

It is possible that dairying was the reason for the wealth which existed at Ashley and which in 1306 gave rise to an intriguing legal reference: Roger Crede of Cosham, son of Walter de Cosham, for burgling Stephen de Aschlegh's house and taking goods to the value of 100s. This was a fortune, equivalent today to perhaps £40,000.[6]

Dairying was given further impetus after the Black Death when the shortage of manpower curtailed arable farming. The surnames Cottle (cattle) and Bollwell (bull), which occur in Box around 1600, hark back to dairy or beef grazing origins.[7]

Box was already characterised by small, enclosed pastoral fields for beef rearing, dairy cows, sheep and goats. After about 1500 cows previously kept as beef sucklers were turned to milk production and Wiltshire butter and cheese was sold in London and other towns.[8] The North Wiltshire dairy industry was a highly developed trade and a wide range of cattle were kept. A century later the local historian John Aubrey said: I have not seen so many pied cattle any where as in North Wiltshire. The county hereabout is much inclined to pied cattle, but commonly the colour is black, or brown, or deep red.[9]

A dairy farm called Weck Farm existed at Ashley. It had a cottage on the land and there was sufficient running water which was needed for cleaning down. The slurry would be used on the next door common field strips. The landlord retained the hay and pasture fields at Ashley (called Ha Grove and Broad Lay) and let out other fields for farming. Above Littlemead there is a property called The Barton, an old word for a farmyard where land had been enclosed to make small closes for cattle.[10] There are four other fields called weeke or wicke in the area, which are dairy farms but too small to be self-sufficient.

The size of medieval dairy herds was minute compared to modern herds. For example, at Whitely, Melksham in about 1550, a herd was recorded as 4 oxen, 5 kine (cows), 4 bullocks under 2 years and 5 yearlings. A wealthy Corsham farmer in 1666 had 7 plough oxen and 12 cows and steers.[11] Oxen were used for ploughing Wiltshire soils until about 1700.

Landlords rarely ran their own dairy operations, preferring instead to rent out pasture land and sell winter fodder to small family farms. This is the origin of the word farmer (where the landlord received a flat-rate fee in advance and allowed the tenant to make as much money as he could out of husbandry; similar to the farming of taxes)[11a]. The farmer in turn sub-contracted the milking work to dairymen by leasing out pregnant cows on an annual contract together with a house and sometimes a dairy. The dairyman earned his living from selling the milk, butter and cheese. Richard Crick in Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles was just such a dairyman and Tess worked as a milkmaid for him.

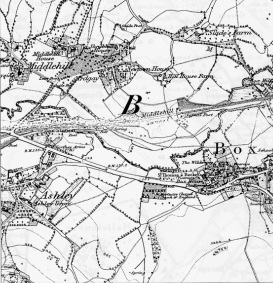

Extensive enclosure in 1630 with the Long's property marked in black

Extensive enclosure in 1630 with the Long's property marked in black

Enclosures in the 1500s

The ownership and control of land altered greatly in the 1500s. It was a very challenging time. The population boomed from 2.4 million in 1520 to 3.3 million in 1570 and 4.5 million by 1600. It was a rate of increase not seen again until the Industrial Revolution. The price of foodstuffs rose steeply with average annual inflation of 0.6% every year throughout the 1540s; 1% every year during the1560s and even more in the 1570s.

Everyone tried to adjust to this rapidly changing situation. Landlords tried to get out of 90 year leases on fixed rents; ambitious yeomen farmers grabbed land, field by field; and everywhere there were complaints against the enclosure of common pasture land taken into private ownership. We can see this at Ashley where small parcels of enclosed dairy land replaced the arable field strips to the east and west of the manor house.

One of the main yeoman families in the area was the Butler family at Ashley. For a brief time the Mountford holdings passed into the ownership of the Butlers when in about 1550 Alice Butler (heiress to the Mountfords through her grandmother) inherited the Ashley land.[12] The Butlers were a prominent regional family, upwardly mobile, and references to them in the parish register include: Richard, son of John Butler 1581; Edward, son, and Edith, wife of John Butler 1582; Henry, son of Richard Butler 1590; William, son of William Butler 1591.[13] Alice's father was William Butler who lived in Badminton, Gloucestershire.

About this time we see how common land was being enclosed and had properties built on it. This probably included the commons (the green) at Ashley, that sparked Paul's question. Squatters homesteads or temporary shacks were erected by landless artisans who set up residence in woodland or common fields until the authorities moved them on. For smallholders the building of a house offered protection and security from life in rough shacks. But house building was closely controlled by the village authorities, such as a special licence Box authorities granted to Anthony Vincent in 1591 to build a cottage.[16]

We can speculate how the enclosure of common land occurred. Theoretically the land was open to everyone to exercise ancient rights to graze animals on grassland, pigs on wasteland and to collect firewood. But the theory had long been unworkable because the village authorities had to control the number of animals each person could graze. As pressure grew on the use of common land, some residents imposed their will to a greater extent than others. They fenced in land to stop open access and they built farmsteads to stop commoners re-entering. These areas became known as the closes.[14] Other houses were built bordering trackways.[15] This was completely different to the old village structure where farmers gathered centrally and walked out to their field strips in the common land.

The ownership and control of land altered greatly in the 1500s. It was a very challenging time. The population boomed from 2.4 million in 1520 to 3.3 million in 1570 and 4.5 million by 1600. It was a rate of increase not seen again until the Industrial Revolution. The price of foodstuffs rose steeply with average annual inflation of 0.6% every year throughout the 1540s; 1% every year during the1560s and even more in the 1570s.

Everyone tried to adjust to this rapidly changing situation. Landlords tried to get out of 90 year leases on fixed rents; ambitious yeomen farmers grabbed land, field by field; and everywhere there were complaints against the enclosure of common pasture land taken into private ownership. We can see this at Ashley where small parcels of enclosed dairy land replaced the arable field strips to the east and west of the manor house.

One of the main yeoman families in the area was the Butler family at Ashley. For a brief time the Mountford holdings passed into the ownership of the Butlers when in about 1550 Alice Butler (heiress to the Mountfords through her grandmother) inherited the Ashley land.[12] The Butlers were a prominent regional family, upwardly mobile, and references to them in the parish register include: Richard, son of John Butler 1581; Edward, son, and Edith, wife of John Butler 1582; Henry, son of Richard Butler 1590; William, son of William Butler 1591.[13] Alice's father was William Butler who lived in Badminton, Gloucestershire.

About this time we see how common land was being enclosed and had properties built on it. This probably included the commons (the green) at Ashley, that sparked Paul's question. Squatters homesteads or temporary shacks were erected by landless artisans who set up residence in woodland or common fields until the authorities moved them on. For smallholders the building of a house offered protection and security from life in rough shacks. But house building was closely controlled by the village authorities, such as a special licence Box authorities granted to Anthony Vincent in 1591 to build a cottage.[16]

We can speculate how the enclosure of common land occurred. Theoretically the land was open to everyone to exercise ancient rights to graze animals on grassland, pigs on wasteland and to collect firewood. But the theory had long been unworkable because the village authorities had to control the number of animals each person could graze. As pressure grew on the use of common land, some residents imposed their will to a greater extent than others. They fenced in land to stop open access and they built farmsteads to stop commoners re-entering. These areas became known as the closes.[14] Other houses were built bordering trackways.[15] This was completely different to the old village structure where farmers gathered centrally and walked out to their field strips in the common land.

Anthony Long's effigy in St Thomas a Becket Church (CMP)

Anthony Long's effigy in St Thomas a Becket Church (CMP)

The Longs at Ashley, 1550 - 1726

After 1550, Alice Butler from Ashley, mentioned above, married Anthony Long of the Long family of South Wraxall.[17] The Longs made their money as clothiers and continued to rise in social status by investing in land.[18]

Anthony Long was a junior member of the family, the fourth of seven sons of Sir Henry Long, but his wealth made him an important local person as can still be seen from the array of insignia and epitaphs in Box church. Anthony’s effigy carries the inscription: Here lyeth the body of Anthony Long, Esqr, buried 2nd of May 1578. John Aubrey describes them: The Longs are now the most flourishing and numerous family in the county.

A legal case in 1583, which defined Alice's entitlement to income from her late husband's estate, described their lands as including: 1,000 acres of land (arable), 500 acres of meadow, 800 acres of pasture, 200 acres of wood.[19]

The family was active in local government but they were unpaid and they reimbursed themselves by exploiting tax advantages and local opportunities. They often had considerable local knowledge, having been involved in the financial and administrative affairs of the monasteries and they took up much monastic land after the dissolution. The Longs were prime movers in the enclosure of land which enabled them to raise revenue from tenants who took up the holding.

After 1550, Alice Butler from Ashley, mentioned above, married Anthony Long of the Long family of South Wraxall.[17] The Longs made their money as clothiers and continued to rise in social status by investing in land.[18]

Anthony Long was a junior member of the family, the fourth of seven sons of Sir Henry Long, but his wealth made him an important local person as can still be seen from the array of insignia and epitaphs in Box church. Anthony’s effigy carries the inscription: Here lyeth the body of Anthony Long, Esqr, buried 2nd of May 1578. John Aubrey describes them: The Longs are now the most flourishing and numerous family in the county.

A legal case in 1583, which defined Alice's entitlement to income from her late husband's estate, described their lands as including: 1,000 acres of land (arable), 500 acres of meadow, 800 acres of pasture, 200 acres of wood.[19]

The family was active in local government but they were unpaid and they reimbursed themselves by exploiting tax advantages and local opportunities. They often had considerable local knowledge, having been involved in the financial and administrative affairs of the monasteries and they took up much monastic land after the dissolution. The Longs were prime movers in the enclosure of land which enabled them to raise revenue from tenants who took up the holding.

Ashley Farmhouse (CMP)

Ashley Farmhouse (CMP)

It was the Longs who substantially developed the area and rebuilt Ashley Manor including a gable end of the south wing in the early 1600s, possibly at the same time as the barn there which is dated 1604.[20] In Francis Allen's map of 1630 the Manor House is shown as a very grand house.[21] They invested their wealth into property and let out land and buildings to tenant farmers.

They also worked their family connections to reinforce their position locally. The vicar of Box, John Coren, married Edith the daughter of Anthony Long of Ashley in 1601 which cemented the union of landlord and church.[22]

This wasn't a total success. Recent views of Coren have depicted him as totally incompetent, frequently accused of immorality, drunkenness and blasphemy.[23] He was also deeply in debt, and a constant litigant who was accused by some of his parishioners of being an unpreaching minister (who) could not rightly nor had no power (authority) to administer the Sacrement.[24]

They also worked their family connections to reinforce their position locally. The vicar of Box, John Coren, married Edith the daughter of Anthony Long of Ashley in 1601 which cemented the union of landlord and church.[22]

This wasn't a total success. Recent views of Coren have depicted him as totally incompetent, frequently accused of immorality, drunkenness and blasphemy.[23] He was also deeply in debt, and a constant litigant who was accused by some of his parishioners of being an unpreaching minister (who) could not rightly nor had no power (authority) to administer the Sacrement.[24]

Sir Edward Northey (photo Martin Northey)

Sir Edward Northey (photo Martin Northey)

The Northey Family, 1726 - 1919

The Northey family took control of Ashley and much of Box after 1726. Their main power base was in Surrey but they invested heavily in Wiltshire and a branch of the family settled in Box.[25]

Sir Edward Northey (1652-1723) founded the dynasty. He was a lawyer who became Attorney-General to two monarchs and acquired substantial property, some of which was at Cheney Court, Manor Farm and Ashley.[26] It was the start of a two hundred year connection between the Northey family and the village.

William Northey II (1722-1770) was married twice. His first wife in 1742 was Harriet Vyner, daughter of Robert, a Lincolnshire MP. The Northey family vault at St Thomas à Becket has a tablet which appears to commemorate Harriet.

William Northey III (1752 -1826) was called Wicked Billy by his family, probably for several reasons. He was a very colourful character, a Member of Parliament for Newport, Wales who rarely attended his public duties at Westminster and gave speeches even less.[27] His reputation probably arose because of his private life. He encouraged the extravagances of the Prince Regent (later George IV) in a manner more lively than respectable at Hazelbury House, which was used as a shooting-box.[28] He was the first Northey to base himself in Box; at Cheney Court, and is sometimes called Wicked Billy of Box.[29]

Wicked Billy died with no legitimate heirs and the Box estate passed to the military side of the Northey family in Epsom. Edward Richard Northey (1795-1878) fought with the Duke of Wellington against Napoleon's troops in the Spanish Peninsular War in 1813 and at Waterloo in 1815. His fourth child, George Wilbraham Northey, who was born in Epsom in 1835, lived at Ashley Manor when he was not serving overseas in the army.

The Northey family took control of Ashley and much of Box after 1726. Their main power base was in Surrey but they invested heavily in Wiltshire and a branch of the family settled in Box.[25]

Sir Edward Northey (1652-1723) founded the dynasty. He was a lawyer who became Attorney-General to two monarchs and acquired substantial property, some of which was at Cheney Court, Manor Farm and Ashley.[26] It was the start of a two hundred year connection between the Northey family and the village.

William Northey II (1722-1770) was married twice. His first wife in 1742 was Harriet Vyner, daughter of Robert, a Lincolnshire MP. The Northey family vault at St Thomas à Becket has a tablet which appears to commemorate Harriet.

William Northey III (1752 -1826) was called Wicked Billy by his family, probably for several reasons. He was a very colourful character, a Member of Parliament for Newport, Wales who rarely attended his public duties at Westminster and gave speeches even less.[27] His reputation probably arose because of his private life. He encouraged the extravagances of the Prince Regent (later George IV) in a manner more lively than respectable at Hazelbury House, which was used as a shooting-box.[28] He was the first Northey to base himself in Box; at Cheney Court, and is sometimes called Wicked Billy of Box.[29]

Wicked Billy died with no legitimate heirs and the Box estate passed to the military side of the Northey family in Epsom. Edward Richard Northey (1795-1878) fought with the Duke of Wellington against Napoleon's troops in the Spanish Peninsular War in 1813 and at Waterloo in 1815. His fourth child, George Wilbraham Northey, who was born in Epsom in 1835, lived at Ashley Manor when he was not serving overseas in the army.

Ordnance Survey map of 1885

Ordnance Survey map of 1885

Later History

The Northeys invested in their properties to increase their rental income needed to support their positions in Westminster and on military service.

Ashley Grove and Lower House were built about 1820-30 and were originally a single property.[30] Ashley Leigh is early 1800s, probably 1820-30. There appears to be a schoolroom or chapel at the east end.[31] Ailsa Craig is also early 1800s.[32]

Ashley House (sometimes called West Ashley House and East Ashley House) is dated about 1840. It is an ornate Italian-style villa with detailed cornices. The property now divides into four: East Ashley House, Lawnwood, Ashley Groome and Ashley Mews.

The Northeys invested in their properties to increase their rental income needed to support their positions in Westminster and on military service.

Ashley Grove and Lower House were built about 1820-30 and were originally a single property.[30] Ashley Leigh is early 1800s, probably 1820-30. There appears to be a schoolroom or chapel at the east end.[31] Ailsa Craig is also early 1800s.[32]

Ashley House (sometimes called West Ashley House and East Ashley House) is dated about 1840. It is an ornate Italian-style villa with detailed cornices. The property now divides into four: East Ashley House, Lawnwood, Ashley Groome and Ashley Mews.

When this property investment strategy was insufficient for their needs, the Northeys had to sell off parts of their estate. In 1873 they held 1,300 acres in the parish but by 1894 this had reduced by almost half.[33]

The number of Northey children caused problems of sub-division because each child required a share of the family inheritance. Edward Richard Northey had seven children; Lieutenant-Colonel George Wilbraham Northey had thirteen children, including George Edward Wilbraham Northey (1860-1932) who based himself at Cheney Court. The recession in Edwardian society hit all ranks of people in the village.

The number of Northey children caused problems of sub-division because each child required a share of the family inheritance. Edward Richard Northey had seven children; Lieutenant-Colonel George Wilbraham Northey had thirteen children, including George Edward Wilbraham Northey (1860-1932) who based himself at Cheney Court. The recession in Edwardian society hit all ranks of people in the village.

Ashley properties in 1919

Ashley properties in 1919

The introduction of Estate Duty tax on property assets valued over £100 introduced in HH Asquith's government of 1908-1915 led to a massive breakup of estates shortly before and immediately after the

First World War.

The Manor of Box and Ashley Estate was sold in 1912, described as one of the best known properties in Wiltshire and Somerset, having been the seat of the Northey family for many years.[34]

The Ashley property comprised nearly 900 acres: a charming little Hamlet of Box, rising from 120 to 600 feet above sea-level, with beautiful views of the distant country.

It was sold as tenanted property including several cottages on Ashley Green itself.

The Ashley property comprised nearly 900 acres: a charming little Hamlet of Box, rising from 120 to 600 feet above sea-level, with beautiful views of the distant country.

It was sold as tenanted property including several cottages on Ashley Green itself.

The sale details of the agent describe it as a Residential, Agricultural or Sporting Estate, being of undulating character; Box Station on the main line of the Great Western Railway is practically on the Property.

|

Property

Ashley Manor Ashley Leigh Ashley Post Office Ashley Cottage Ailsa Craig Ashley Green Cottage Ashley Green Cottages & Allotments |

Principal Tenant

Rev AV Gregoire & TT Perkins Col Parkinson - C Botcherby R Davies G Pritchard Various |

Acreage (a.r.p) [35]

9.3.31 1.0.6 0.0.12 0.1.2 0.0.26 1.0.7 1.3.27 |

Rent (£.s.d)

£150.0.0 £40.2.6 £12.0.0 £35.0.0 £13.0.0 £12.15.0 £40.14.0 |

The sale particulars give an interesting view of the extent of the estate at that time including Kingsdown Golf Links, Longsplatt Quarry, Private Water Works and numerous farms and farmhouses. It was an appropriate time to sell as the Smallholdings Act of 1907 gave help to small farmers particularly in dairy.[36]

Some parts of the Northey Estates survived longer. Parts of the freehold estate were sold in 1919 including Hazelbury. Hazelbury Manor had fallen into decline and in 1919 Major-General Sir Edward Northey sold it to George Jardine Kidston, the notable historian of Hazelbury. Slades Farm was sold in 1964.[37]

The sale of the Northey estates marked the end of landlord control of the village, the conclusion of a period that had lasted centuries. It was also the opening of a new chapter in Box’s story.

Some parts of the Northey Estates survived longer. Parts of the freehold estate were sold in 1919 including Hazelbury. Hazelbury Manor had fallen into decline and in 1919 Major-General Sir Edward Northey sold it to George Jardine Kidston, the notable historian of Hazelbury. Slades Farm was sold in 1964.[37]

The sale of the Northey estates marked the end of landlord control of the village, the conclusion of a period that had lasted centuries. It was also the opening of a new chapter in Box’s story.

Putting on a new extension (Paul Bazell)

Putting on a new extension (Paul Bazell)

Modern Times

Paul Bazell has brought the story of Ashley Green fully up to date with the following article in February 2014.

The only recent history that I know of is that we purchased Ashley Green in the summer of 2008 from the Oatley family who had lived there for 50 years. We believe the house may have originally been the wash house for Ashley Manor. The owners who we bought from said that they thought the house dated back to the 1600s.

We carried out a major refurbishment and extension to the house whilst we lived with our daughter Katie (and her husband Justin) in Tring, Herts for 5 months. I ended up renting a caravan and parking it up outside the house and living in it with one of my sons and one of our dogs for the last 6 weeks of the contract, mainly to push it on and deal with the decisions on finishings whilst the remainder of the family and pets stayed in Tring.

Importantly I rigged up a small office in the caravan (including internet access) to enable me to carry on with my business (building/ refurbishment contractor in central London) and of course Sky TV for evening entertainment - Those 6 weeks were memorable for all sorts of reasons, my son Greg was a big help in those stressful times.

Paul Bazell has brought the story of Ashley Green fully up to date with the following article in February 2014.

The only recent history that I know of is that we purchased Ashley Green in the summer of 2008 from the Oatley family who had lived there for 50 years. We believe the house may have originally been the wash house for Ashley Manor. The owners who we bought from said that they thought the house dated back to the 1600s.

We carried out a major refurbishment and extension to the house whilst we lived with our daughter Katie (and her husband Justin) in Tring, Herts for 5 months. I ended up renting a caravan and parking it up outside the house and living in it with one of my sons and one of our dogs for the last 6 weeks of the contract, mainly to push it on and deal with the decisions on finishings whilst the remainder of the family and pets stayed in Tring.

Importantly I rigged up a small office in the caravan (including internet access) to enable me to carry on with my business (building/ refurbishment contractor in central London) and of course Sky TV for evening entertainment - Those 6 weeks were memorable for all sorts of reasons, my son Greg was a big help in those stressful times.

New roof finished

New roof finished

I have now retired at the age of 55 (as planned) and am embarking on working / improving the paddock, gardens, workshop and general outside areas to Ashley Green.

Hilary, my wife still works 1 or 2 days a week in London with long established clients as a personal fitness coach/advisor and we are now both enjoying being new grand parents.

Our eldest son is currently touring the world with his girlfriend Bridget, coming back in March 2014.

Hilary, my wife still works 1 or 2 days a week in London with long established clients as a personal fitness coach/advisor and we are now both enjoying being new grand parents.

Our eldest son is currently touring the world with his girlfriend Bridget, coming back in March 2014.

References

[1] JEB Gover, Allen Mawer & FM Stenton, The Place-names of Wiltshire,1939, Cambridge University Press p.85

[2] GF Laurence, Ashley Manor, Box, 1994, Wiltshire History Centre

[3] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.125 & 127

[4] GF Laurence, Ashley Manor, Box

[5] GF Laurence, Ashley Manor, Box

[6] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 33, p.115

[7] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, The Downland Pres,p.54-5

[8] JH Bettey, Rural Life in Wessex 1500-1900, 1987, Alan Sutton, p14

[9] John Aubrey, The Natural History of Wiltshire, 1969, David & Charles Reprint, p.61

[10] Pamela M Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1800, 1989, Devizes Books Press, p.8, 16, 63

[11] Pamela M Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings, p.63

[11a] The sale to private individuals of the right to collect and keep national taxes (eg customs duties) in return for an up-front, discounted payment to government - similar in principle to renting out farmland and allowing the tenant to keep the income.

[12] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, 1862, Longman, p.57

[13] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, p.56

[14] John Hare, A Prospering Society, p.17

[15] www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/england/wiltshire/box

[16] WRS, Vol 3, p.142

[17] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, p.57

[18] George W Marshall, The Visitation of Wiltshire 1623, 1882, George Bell & Sons, p.47

[19] Inquisitiones Post Mortem, Henry Long, 22nd September 1629, p.86-7

[20] WRO ref L1/WILTM: F402.16-7

[21] Francis Allen's map in Kidston

[22] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.55

[23] Martin Ingram, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England 1570-1640, p.110

[24] BH Cunniston, Records of the County of Wilts, 1932, Devizes, p.5

[25] This section is indebted to www.epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/WoodcoteHouse.html

[26] http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1690-1715/member/northey-sir-edward-1652-1723

[27] www.historyofparliamentonline.org

[28] http://www.epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/WoodcoteHouse.html

[29] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, p.245

[30] www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/england/wiltshire/box

[31] www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/england/wiltshire/box

[32] www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/england/wiltshire/box

[33] Victoria County History, Vol IV, p.106

[34] Sale Particulars www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/a2a/records.aspx?cat=190-1265&cid=-1#-1, Wiltshire History Centre 1265/4 1912

[35] Imperial measurement of acres, roods and perches

[36] Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066-1945, 1987, Harper Collins, p.565-6

[37] Countryside Treasures, Wiltshire History Centre

[1] JEB Gover, Allen Mawer & FM Stenton, The Place-names of Wiltshire,1939, Cambridge University Press p.85

[2] GF Laurence, Ashley Manor, Box, 1994, Wiltshire History Centre

[3] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.125 & 127

[4] GF Laurence, Ashley Manor, Box

[5] GF Laurence, Ashley Manor, Box

[6] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 33, p.115

[7] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, The Downland Pres,p.54-5

[8] JH Bettey, Rural Life in Wessex 1500-1900, 1987, Alan Sutton, p14

[9] John Aubrey, The Natural History of Wiltshire, 1969, David & Charles Reprint, p.61

[10] Pamela M Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1800, 1989, Devizes Books Press, p.8, 16, 63

[11] Pamela M Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings, p.63

[11a] The sale to private individuals of the right to collect and keep national taxes (eg customs duties) in return for an up-front, discounted payment to government - similar in principle to renting out farmland and allowing the tenant to keep the income.

[12] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, 1862, Longman, p.57

[13] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, p.56

[14] John Hare, A Prospering Society, p.17

[15] www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/england/wiltshire/box

[16] WRS, Vol 3, p.142

[17] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, p.57

[18] George W Marshall, The Visitation of Wiltshire 1623, 1882, George Bell & Sons, p.47

[19] Inquisitiones Post Mortem, Henry Long, 22nd September 1629, p.86-7

[20] WRO ref L1/WILTM: F402.16-7

[21] Francis Allen's map in Kidston

[22] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.55

[23] Martin Ingram, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England 1570-1640, p.110

[24] BH Cunniston, Records of the County of Wilts, 1932, Devizes, p.5

[25] This section is indebted to www.epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/WoodcoteHouse.html

[26] http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1690-1715/member/northey-sir-edward-1652-1723

[27] www.historyofparliamentonline.org

[28] http://www.epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/WoodcoteHouse.html

[29] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, p.245

[30] www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/england/wiltshire/box

[31] www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/england/wiltshire/box

[32] www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/england/wiltshire/box

[33] Victoria County History, Vol IV, p.106

[34] Sale Particulars www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/a2a/records.aspx?cat=190-1265&cid=-1#-1, Wiltshire History Centre 1265/4 1912

[35] Imperial measurement of acres, roods and perches

[36] Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066-1945, 1987, Harper Collins, p.565-6

[37] Countryside Treasures, Wiltshire History Centre