Ashley Barn Site, 1982 Text and photos Abi Sherriff July 2023

Above Left: the two barns and habitat of the site with water trough beyond gate and Right: close-up of old barn with half-timber door

When Abi Sherirff was a teenager studying for her National Nursery Examination Board (NNEB) exams in Bristol, she carried out a year-long study of a derelict area of wasteland at Ashley, just up from Ashley Manor and close to her mother’s house at Newby, Doctor’s Hill. This article gives extracts of Abi’s research in her own words in 1982.

Introduction

The site I have chosen to study consists of old-farmland now wasteland, 200 yards long and 80 yards wide, with two barns, a metal aluminium trough and a group of symmetrically-planted trees. The site is bordered by a hedge on one side and an old natural stone wall, held together by cement but no longer very neat. The land is owned by a Middlehill farmer from the other side of Box Valley, although most other land in the area belongs to an Ashley farmer. Most of the area was once owned by Ashley Manor and, where there are now new houses, once were courtyards and stables.

My project is due to last 8-10 months. Throughout this time, I shall have made several visits (approximately one a month) and

I will record my observations and whenever possible collect samples of plants and portray the habitat with photographs.

My winter visits will be shorter due to nature’s period of inactivity, when I will try to gain background information. The intention of this project is to illustrate just how much goes on in the environment around us and how the various elements affect the pattern of nature, including man’s influence.

First Visit, 17 July 1982, 11:15 am

Sunshine but sky cloudy with quite a strong wind blowing. Although they are side by side, the two barns are constructed differently. One has wooden posts and a corrugated iron roof. It is virtually open apart from a back wall and the wall it shares with the second barn. This second barn is older, built of stone with a slate tiled roof. At one time it may have been a stable as it has half doors. Today, both barns are full of hay. The first thing I noticed was a small black object on a bale of hay, a dead black cat. Behind the trough is an ivy-covered wall, leading to the gate with a hedge running the length of the field and a small, but old, hawthorn tree.

The site I have chosen to study consists of old-farmland now wasteland, 200 yards long and 80 yards wide, with two barns, a metal aluminium trough and a group of symmetrically-planted trees. The site is bordered by a hedge on one side and an old natural stone wall, held together by cement but no longer very neat. The land is owned by a Middlehill farmer from the other side of Box Valley, although most other land in the area belongs to an Ashley farmer. Most of the area was once owned by Ashley Manor and, where there are now new houses, once were courtyards and stables.

My project is due to last 8-10 months. Throughout this time, I shall have made several visits (approximately one a month) and

I will record my observations and whenever possible collect samples of plants and portray the habitat with photographs.

My winter visits will be shorter due to nature’s period of inactivity, when I will try to gain background information. The intention of this project is to illustrate just how much goes on in the environment around us and how the various elements affect the pattern of nature, including man’s influence.

First Visit, 17 July 1982, 11:15 am

Sunshine but sky cloudy with quite a strong wind blowing. Although they are side by side, the two barns are constructed differently. One has wooden posts and a corrugated iron roof. It is virtually open apart from a back wall and the wall it shares with the second barn. This second barn is older, built of stone with a slate tiled roof. At one time it may have been a stable as it has half doors. Today, both barns are full of hay. The first thing I noticed was a small black object on a bale of hay, a dead black cat. Behind the trough is an ivy-covered wall, leading to the gate with a hedge running the length of the field and a small, but old, hawthorn tree.

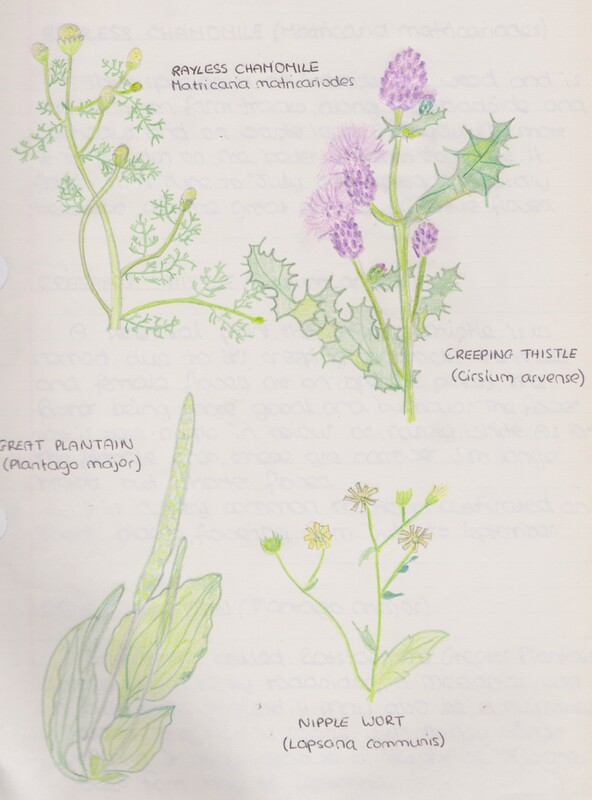

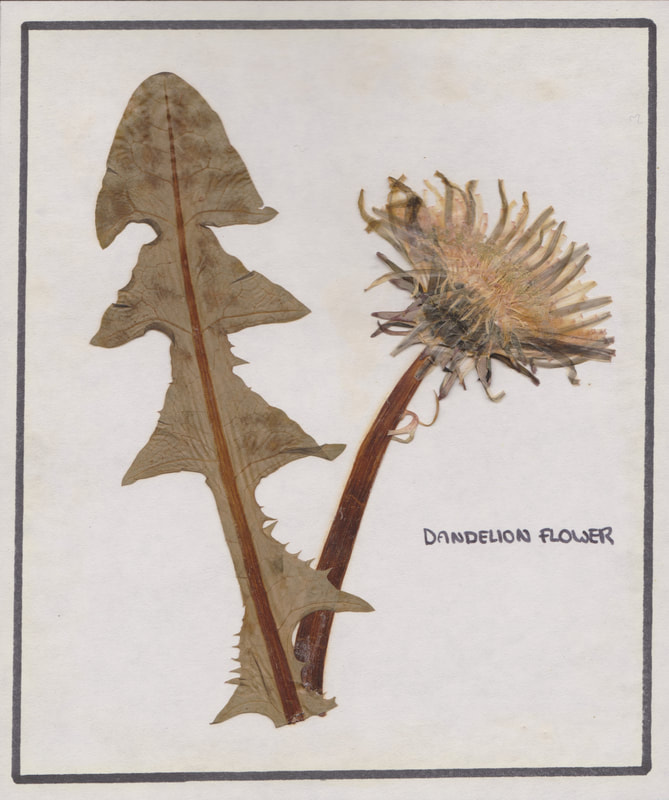

Most of the ground is covered in wild plants in large clusters. The plants I discovered include dandelions, dock leaves, brambles, thistles, nettles, speedwell, great plantain, Rayless Chamomile, Good King Henry, nipple-wort, hawthorn, ivy, couch grass. The Good King Henry was once used as a vegetable and boiled, similar to spinach. Not native, it has since naturalised near villages and farms. The Rayless Chamomile is a very common, wasteland weed. When the leaves are crushed, they smell of pineapple. It is thought to have come from Oregon, USA. On the thistles, almost one to every flower, was a small beetle, about 1½ cms long, bright orange in colour with a black tip at the end of its body

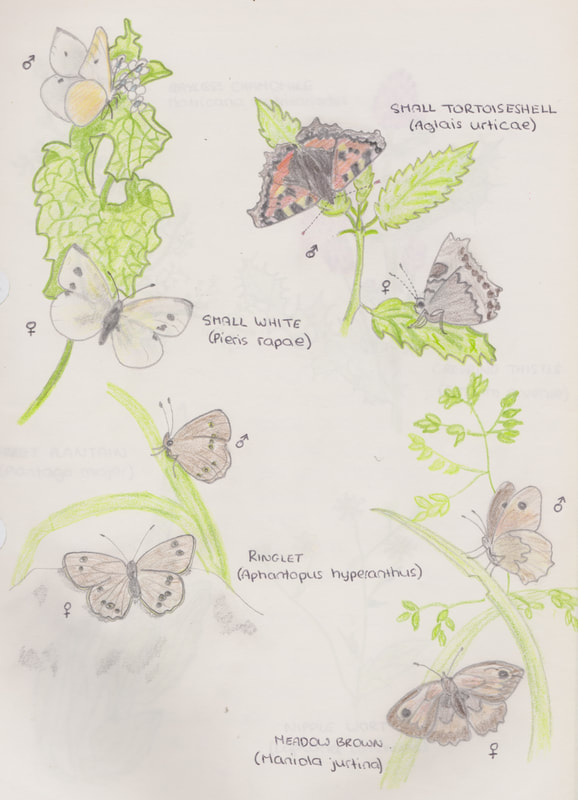

As well as the dead cat, woodlice, spiders and orange beetle, I found several species of butterfly – Small White, Small Tortoiseshell, Meadow Brown and Ringlet. The Meadow Brown is common throughout the British Isles, in fields, meadows and woodland clearings. There are two broods a year which overlap, giving the appearance that the butterfly is continuously around. The Meadow Brown is easily recognisable with a spot on each of its forewings and it flies in a slow, lazy way. The small tortoiseshell is found in almost any type of habitat, feeding eagerly in gardens, particularly buddleia, sedum and Michaelmas Daisy. Directly after the eggs hatch, the larvae spin a silk thread over the leaves of the nettle and feed on the plant. The pupae suspend by tail hooks of silk attached to the stem of the plant. The ringlet has only one generation a year. It is a restless butterfly and takes frequent, short flights, showing a distinct preference for shade and scattering its eggs freely amongst the grass.

I had to look into the trough for some minutes as it was murky and somewhat overgrown. Then I spotted a couple of tiny, larvae-like creatures ½ cm in length with their mouths attached to the surface film of the water and their bodies dangling beneath.

They wriggled here and there at quite a speed.

I had to look into the trough for some minutes as it was murky and somewhat overgrown. Then I spotted a couple of tiny, larvae-like creatures ½ cm in length with their mouths attached to the surface film of the water and their bodies dangling beneath.

They wriggled here and there at quite a speed.

Second Visit 29 August 1982, 2:15pm

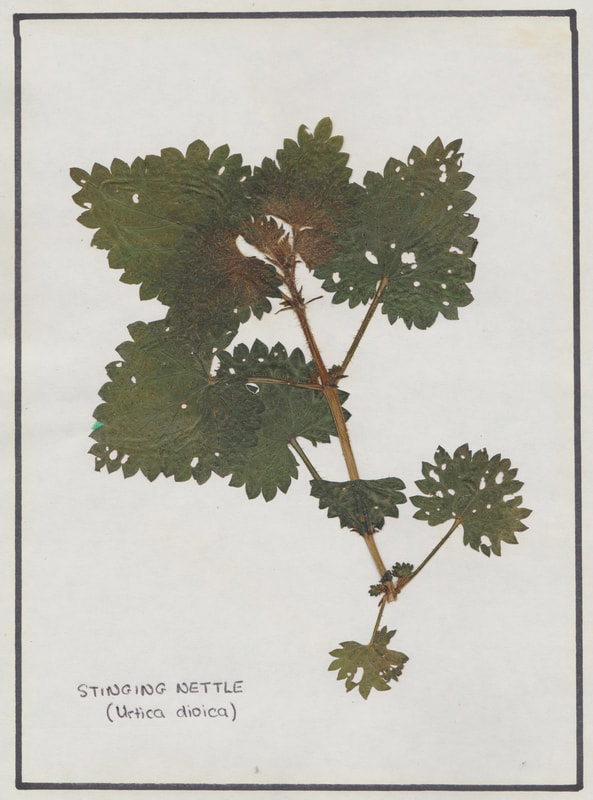

The weather was sunny and warm with a blustery wind. What hit me first was the emptiness and clearing of the vegetation. All the stinging nettles had been cut along with patches of thistles. There was a strong smell of cows and a lot of the ground cover had gone, died down, trampled or been eaten. Beyond the site boundary, I could see a small herd of young Friesians huddled together.

The water in the trough was now very clear with a layer of silt on the bottom covered in leaves, straw and twigs. Apart from a drowning fly, there were no water creatures. Most of the remaining thistles had gone to seed, looking like dandelion seeds. When the wind blew, the thistles seeds were scattered, giving the appearance of flying insects. No orange beetles left, replaced by snails and spiders. I could hear grasshoppers but could not see them, just the rustling of the surrounding trees.

After twenty minutes I saw a single butterfly and under the stones was not a solitary insect, not even a woodlouse. The dead cat was still there in exactly the same place, its body decomposing but recognisable by its facial features. Compared to my previous visit, the habitat was almost a ghost town, the hive of activity now dispelled.

Third Visit 23 September 1982, 4:30pm

The weather was overcast and damp. The ground of the habitat was thick with mud and cow muck, covering all the plants and even the stones on the floor. The newer barn was still full of hay but the stable door of the other had a bent over nail in it, preventing it from opening. I heard heavy breathing behind me and turned round to see a herd of a dozen curious Friesian bullocks who had arrived from the field to discover what I was doing. I had a quick chat with them and squelched my way round to the back of the barn. There was no sign of animal life, just a group of trees in three rows of about nine trees in each: beech, horse chestnut, oak and beech (by far the most dominant).

The hedge offered more possibilities. To the casual on-looker it is just a divider of fields but it is a living, vital community with many insects, small plants and animals. The hedges planted to enclose fields in the sixteenth century usually started as a single species, mainly hazel, hawthorn or blackthorn. But in succeeding years they have often been colonised by other species of shrub, perhaps one species emerging every hundred years, so that older hedges tend to have the most species. I only found hawthorn growing in my hedge, so it could have been about 100 years old.

Fourth Visit 29 October 1982, 9:00am

I found very little different between my third and fourth visit apart from the thicker mud and brown and grey colours as most trees had shed their leaves, particularly the horse chestnut. The chestnut was introduced to Britain from Greece in the 15th century and tends to grow in parks and gardens rather than woodland. The buds are easily recognisable with their numerous wrap layers and resin coating of the sticky bud. The resin melts daily in the sunshine and gives the buds a topcoat of polish. The leaves separate and assume a horizontal position, reaching up to 18 inches across. Trees do not produce conker fruit until they are about 20 years old. Horses do not eat the conkers as they are too bitter, although cattle, deer and sheep are fond of them. This is still much quicker than the oak, which produces acorns after 60 or 70 years. The wood is unsuitable for timber until it is 150 years old. The thick, rough bark is deeply furrowed and affords a temporary hiding place for insects. The blossom can be male (catkins) and the female flower becomes the cup that holds the acorn.

The weather was sunny and warm with a blustery wind. What hit me first was the emptiness and clearing of the vegetation. All the stinging nettles had been cut along with patches of thistles. There was a strong smell of cows and a lot of the ground cover had gone, died down, trampled or been eaten. Beyond the site boundary, I could see a small herd of young Friesians huddled together.

The water in the trough was now very clear with a layer of silt on the bottom covered in leaves, straw and twigs. Apart from a drowning fly, there were no water creatures. Most of the remaining thistles had gone to seed, looking like dandelion seeds. When the wind blew, the thistles seeds were scattered, giving the appearance of flying insects. No orange beetles left, replaced by snails and spiders. I could hear grasshoppers but could not see them, just the rustling of the surrounding trees.

After twenty minutes I saw a single butterfly and under the stones was not a solitary insect, not even a woodlouse. The dead cat was still there in exactly the same place, its body decomposing but recognisable by its facial features. Compared to my previous visit, the habitat was almost a ghost town, the hive of activity now dispelled.

Third Visit 23 September 1982, 4:30pm

The weather was overcast and damp. The ground of the habitat was thick with mud and cow muck, covering all the plants and even the stones on the floor. The newer barn was still full of hay but the stable door of the other had a bent over nail in it, preventing it from opening. I heard heavy breathing behind me and turned round to see a herd of a dozen curious Friesian bullocks who had arrived from the field to discover what I was doing. I had a quick chat with them and squelched my way round to the back of the barn. There was no sign of animal life, just a group of trees in three rows of about nine trees in each: beech, horse chestnut, oak and beech (by far the most dominant).

The hedge offered more possibilities. To the casual on-looker it is just a divider of fields but it is a living, vital community with many insects, small plants and animals. The hedges planted to enclose fields in the sixteenth century usually started as a single species, mainly hazel, hawthorn or blackthorn. But in succeeding years they have often been colonised by other species of shrub, perhaps one species emerging every hundred years, so that older hedges tend to have the most species. I only found hawthorn growing in my hedge, so it could have been about 100 years old.

Fourth Visit 29 October 1982, 9:00am

I found very little different between my third and fourth visit apart from the thicker mud and brown and grey colours as most trees had shed their leaves, particularly the horse chestnut. The chestnut was introduced to Britain from Greece in the 15th century and tends to grow in parks and gardens rather than woodland. The buds are easily recognisable with their numerous wrap layers and resin coating of the sticky bud. The resin melts daily in the sunshine and gives the buds a topcoat of polish. The leaves separate and assume a horizontal position, reaching up to 18 inches across. Trees do not produce conker fruit until they are about 20 years old. Horses do not eat the conkers as they are too bitter, although cattle, deer and sheep are fond of them. This is still much quicker than the oak, which produces acorns after 60 or 70 years. The wood is unsuitable for timber until it is 150 years old. The thick, rough bark is deeply furrowed and affords a temporary hiding place for insects. The blossom can be male (catkins) and the female flower becomes the cup that holds the acorn.

Fifth Visit 13 November 1982, 10:55am

Cold and sharp with a quite clear sky after a sharp frost. As it was late autumn, I was rather surprised about the amount of green vegetation since my last visit, mainly grass and even some young stinging nettles. The stinging comes from the tips of the leaves which break off when touched, releasing acid from the hairs covering the leaves. In country districts, the young nettle shoots were sometimes cooked and eaten during the Second World War, the chlorophyll extracted for use in medicines and the green dye for colouring camouflage. The plants have only male or female flowers and pollen is carried between them by the wind. The cows had gone by the time of this visit, allowing the grass to grow through the mud. Standing listening for a few moments, I could hear bird song, a sparrow and a blackbird.

Sixth and Seventh Visits 7 December 1982 and 15 January 1983

There is little to report in these winter visits with new life virtually at a standstill, apart from the chickweed showing as a very green colour.

Eighth Visit 17 February 1983, 12:00 noon

The weather was sunny but very cold without a cloud in the blue sky and a sharp wind. Someone had been to the site as, in front of the barn was a machine with four wheels and a sort of conveyor belt with the word “Lister” on it. On further inspection, I concluded it was used for moving bales of hay or straw. Despite this activity, the dead cat was still there untouched, perhaps slightly more skeletal.

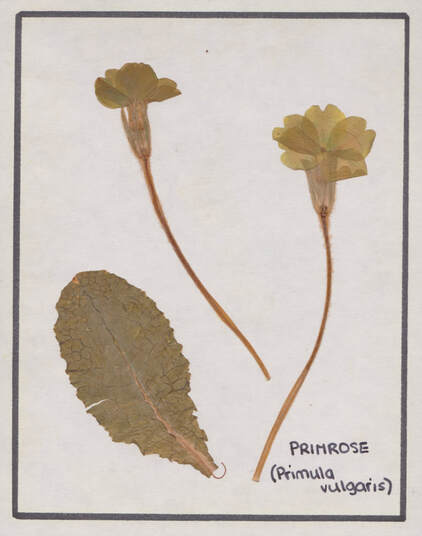

I moved away into the outside where the ground was still frozen with frost lingering along the length of the hedge. I noticed some primroses, small and not quite open. I collected moss which dominated the stones and wood under the hedge. The water in the trough was frozen thick and I decided to take bark rubbings of the trees. One horse chestnut had died for a reason unknown and shed its bark.

Cold and sharp with a quite clear sky after a sharp frost. As it was late autumn, I was rather surprised about the amount of green vegetation since my last visit, mainly grass and even some young stinging nettles. The stinging comes from the tips of the leaves which break off when touched, releasing acid from the hairs covering the leaves. In country districts, the young nettle shoots were sometimes cooked and eaten during the Second World War, the chlorophyll extracted for use in medicines and the green dye for colouring camouflage. The plants have only male or female flowers and pollen is carried between them by the wind. The cows had gone by the time of this visit, allowing the grass to grow through the mud. Standing listening for a few moments, I could hear bird song, a sparrow and a blackbird.

Sixth and Seventh Visits 7 December 1982 and 15 January 1983

There is little to report in these winter visits with new life virtually at a standstill, apart from the chickweed showing as a very green colour.

Eighth Visit 17 February 1983, 12:00 noon

The weather was sunny but very cold without a cloud in the blue sky and a sharp wind. Someone had been to the site as, in front of the barn was a machine with four wheels and a sort of conveyor belt with the word “Lister” on it. On further inspection, I concluded it was used for moving bales of hay or straw. Despite this activity, the dead cat was still there untouched, perhaps slightly more skeletal.

I moved away into the outside where the ground was still frozen with frost lingering along the length of the hedge. I noticed some primroses, small and not quite open. I collected moss which dominated the stones and wood under the hedge. The water in the trough was frozen thick and I decided to take bark rubbings of the trees. One horse chestnut had died for a reason unknown and shed its bark.

Above: The site in January 1983. Left: The main barn and Right: The gate and corrugated iron barn

Ninth and Tenth Visits 25 March 1983, 6.30pm Dusk and 6 April 1983, 2:10pm

Approaching the site in wet and windy weather, a female blackbird flew across my path. At the top of one of the trees I noticed a crow’s nest and although the base of the tree were bird droppings. I looked for bats and rabbits but perhaps it was not yet quite dark enough for them. Within the last month, all kinds of plants had appeared on the surface and the ground cover had become fairly dense. I collected several specimens and pressed samples, especially from the trees at the back of the site, which were more protected from the cows.

Most of the hay from the new barn had been used and the remaining bales strewn across the floor. The dead cat and its bale had gone but, on the ground, were three of its vertebrae which I collected in a matchbox. The farmer has been on the site and protected the remaining hay bales from the cows using a length of iron bar. Despite the high wind, I could hear birds singing, probably blackbirds. Due to the recent rain and hail showers the ground is boggy underfoot.

Eleventh Visit 19 April 1983, 7:00pm

This was my last visit to the site in sunny but quite cold weather. No plants were in flower yet but everything looked greener and more abundant. Buds in the hedgerow were coming out at a fast rate, none apparent in the oaks, beech buds still tightly closed but the horse chestnut buds well on the way.

There was an air of peace and quiet with the cows getting ready for spring and summer grazing in the very green field beyond the site as the seasons renewed themselves.

Conclusion

This concluded my project over nine months and eleven visits. During the first few visits, there was an abundance of plant life and a variety of insects including butterflies. The atmosphere was of intense activity with the buzzing of bees and flies, the sway and rustle of the thistles in the breeze. This gave way to a peaceful calm and tranquillity in the summer sun and later changing into rain and mud with the inevitable decline in vegetation and insects as they began their annual hibernation.

Browns and yellows replaced the green vegetation as autumn approached, then a bareness with a definite and deep silence shrouded by a carpet of decaying matter. By January, the site was beginning to be more active after a mild winter. March was by far the most profitable for collecting specimens and life came so quickly within weeks of starting. I was disappointed with the lack of animal life to record but being part of a farm unit meant that the site had a lot of human influence.

Approaching the site in wet and windy weather, a female blackbird flew across my path. At the top of one of the trees I noticed a crow’s nest and although the base of the tree were bird droppings. I looked for bats and rabbits but perhaps it was not yet quite dark enough for them. Within the last month, all kinds of plants had appeared on the surface and the ground cover had become fairly dense. I collected several specimens and pressed samples, especially from the trees at the back of the site, which were more protected from the cows.

Most of the hay from the new barn had been used and the remaining bales strewn across the floor. The dead cat and its bale had gone but, on the ground, were three of its vertebrae which I collected in a matchbox. The farmer has been on the site and protected the remaining hay bales from the cows using a length of iron bar. Despite the high wind, I could hear birds singing, probably blackbirds. Due to the recent rain and hail showers the ground is boggy underfoot.

Eleventh Visit 19 April 1983, 7:00pm

This was my last visit to the site in sunny but quite cold weather. No plants were in flower yet but everything looked greener and more abundant. Buds in the hedgerow were coming out at a fast rate, none apparent in the oaks, beech buds still tightly closed but the horse chestnut buds well on the way.

There was an air of peace and quiet with the cows getting ready for spring and summer grazing in the very green field beyond the site as the seasons renewed themselves.

Conclusion

This concluded my project over nine months and eleven visits. During the first few visits, there was an abundance of plant life and a variety of insects including butterflies. The atmosphere was of intense activity with the buzzing of bees and flies, the sway and rustle of the thistles in the breeze. This gave way to a peaceful calm and tranquillity in the summer sun and later changing into rain and mud with the inevitable decline in vegetation and insects as they began their annual hibernation.

Browns and yellows replaced the green vegetation as autumn approached, then a bareness with a definite and deep silence shrouded by a carpet of decaying matter. By January, the site was beginning to be more active after a mild winter. March was by far the most profitable for collecting specimens and life came so quickly within weeks of starting. I was disappointed with the lack of animal life to record but being part of a farm unit meant that the site had a lot of human influence.

Abi’s work charmingly recorded a largely unchanging habitat and the continuous cycle of nature with limited human interaction. But her story also comes from a bygone age before global warming and climate change were fully identified. The site was later sold and redeveloped with an attractive new residence and garden. It now remains for us to rediscover what we should do with the natural world and how it is impacted by our needs as a human species. We are just on the brink of new ways of doing this with rewilding, no-mow May and a desire to help nature.