Anglo-Saxon Evidence in Early Medieval Box Alan Payne and Jonathan Parkhouse, August 2020

We saw from earlier articles that we need a sophisticated narrative to explain early medieval Box, contrary to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's narrative of invasion and replacement of Romano-British culture by Germanic settlers. One authority has described these changes as indicating "an emergent, largely native, post-Roman society forging a new distinct cultural identity".[1]

With no archaeological finds or documentary sources in Box, we need to focus on other available evidence.

With no archaeological finds or documentary sources in Box, we need to focus on other available evidence.

Place-names

There are a several place-names derived from Old English words still in use in the village such as Hazelbury, Ditteridge, Henley and Ashley. The latter two are topographical composite words using the suffix leah, (a farm area created out of forest clearings. later used to describe meadow). There are also a few significant fieldnames in the 1840 Tithe Apportionment Records. These include Charlands (meaning the coerls lands) at Alcombe (refs 258 and 280) and Charlwood also from churl (peasant) refs 699 and 701a). But these are the haphazard residue of Old English derivatives and tell us nothing about the date of their adoption. There seems to have been a degree of settlement shift in many areas during the mid-Saxon period and these terms could have been applied as a descriptive name any time before or after the Norman conquest.

Some etymologists have attempted to associate topographical names, such as woods, hills and streams, with early settlement-names.[2] There are occurrences of these in the field-names of Box including -dun ("hill" as in Kingsdown), -hãm ("homestead" in Fogham), -feld ("open land" in several different locations), and -lëah ("wood/ clearing" as in The Ley). In 1630 Leyes was a field, an area of common pasture where animals could graze freely and securely close to the centre of the village and the Ley road is still the border of a low-lying, secure area. But there is no evidence that these names were used pre-conquest and the dating of the village by their use is uncertain.

There are a several place-names derived from Old English words still in use in the village such as Hazelbury, Ditteridge, Henley and Ashley. The latter two are topographical composite words using the suffix leah, (a farm area created out of forest clearings. later used to describe meadow). There are also a few significant fieldnames in the 1840 Tithe Apportionment Records. These include Charlands (meaning the coerls lands) at Alcombe (refs 258 and 280) and Charlwood also from churl (peasant) refs 699 and 701a). But these are the haphazard residue of Old English derivatives and tell us nothing about the date of their adoption. There seems to have been a degree of settlement shift in many areas during the mid-Saxon period and these terms could have been applied as a descriptive name any time before or after the Norman conquest.

Some etymologists have attempted to associate topographical names, such as woods, hills and streams, with early settlement-names.[2] There are occurrences of these in the field-names of Box including -dun ("hill" as in Kingsdown), -hãm ("homestead" in Fogham), -feld ("open land" in several different locations), and -lëah ("wood/ clearing" as in The Ley). In 1630 Leyes was a field, an area of common pasture where animals could graze freely and securely close to the centre of the village and the Ley road is still the border of a low-lying, secure area. But there is no evidence that these names were used pre-conquest and the dating of the village by their use is uncertain.

Saxon Occupation

It is unlikely that a Saxon treasure hoard would be buried where there was domestic farming because of the likelihood of accidental discovery but what about a Saxon residence? A grubenhaus (sunken-featured building often thought to be craft workshop or storage building) has been found in Chippenham but probably we will never find evidence of Saxon residential occupation in central Box either of Saxon halls or farmhouses.[3] Sometimes occupation is determined just by postholes where the colour and texture of soil differs, the wooden building and thatch roof having entirely rotted away. The evidence is less highly visible than that (for example) of the Roman or late medieval periods. Unless we strike lucky, it may be that the centre of the village has been rebuilt too many times for evidence to remain.

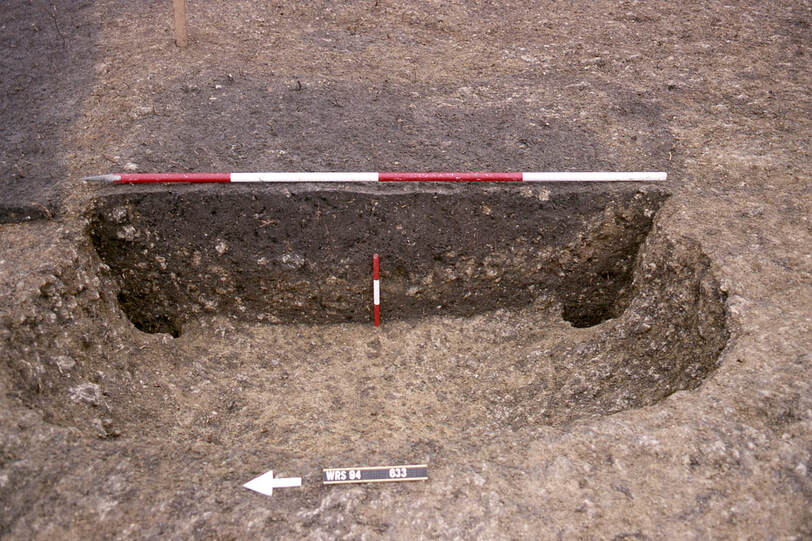

A number of Saxon-style buildings have been found in north Wiltshire, both sunken-featured structures and timber framed-buildings have been uncovered in Trowbridge and Swindon. In Old Town, Swindon, archaeologists found a large, timber building with plaster wall coverings and several domestic goods.[4] The pictures in this article are of early Saxon-style buildings excavated in Buckinghamshire. The headline photograph is of a grubenhaus; the one below is of a small post-built timber hall. They are both from the site of Walton, on the southern side of Aylesbury, where the Walton name indicates a settlement occupied by people identified (whether by themselves or their neighbours) as walh (Britons) whilst living in structures conventionally categorised as Anglo-Saxon. The Aylesbury site is an example of an early invasion conflict location where, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Cuthwulf fought against the Britons at Bedcanford (unidentified) and captured four villages, including Aylesbury. Aylesbury itself was the site of an Iron-Age hillfort and was to become the site of an Anglo-Saxon minster church, perhaps during the 700s. The Walton buildings are probably a century or so earlier than the minster.

It is unlikely that a Saxon treasure hoard would be buried where there was domestic farming because of the likelihood of accidental discovery but what about a Saxon residence? A grubenhaus (sunken-featured building often thought to be craft workshop or storage building) has been found in Chippenham but probably we will never find evidence of Saxon residential occupation in central Box either of Saxon halls or farmhouses.[3] Sometimes occupation is determined just by postholes where the colour and texture of soil differs, the wooden building and thatch roof having entirely rotted away. The evidence is less highly visible than that (for example) of the Roman or late medieval periods. Unless we strike lucky, it may be that the centre of the village has been rebuilt too many times for evidence to remain.

A number of Saxon-style buildings have been found in north Wiltshire, both sunken-featured structures and timber framed-buildings have been uncovered in Trowbridge and Swindon. In Old Town, Swindon, archaeologists found a large, timber building with plaster wall coverings and several domestic goods.[4] The pictures in this article are of early Saxon-style buildings excavated in Buckinghamshire. The headline photograph is of a grubenhaus; the one below is of a small post-built timber hall. They are both from the site of Walton, on the southern side of Aylesbury, where the Walton name indicates a settlement occupied by people identified (whether by themselves or their neighbours) as walh (Britons) whilst living in structures conventionally categorised as Anglo-Saxon. The Aylesbury site is an example of an early invasion conflict location where, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Cuthwulf fought against the Britons at Bedcanford (unidentified) and captured four villages, including Aylesbury. Aylesbury itself was the site of an Iron-Age hillfort and was to become the site of an Anglo-Saxon minster church, perhaps during the 700s. The Walton buildings are probably a century or so earlier than the minster.

Settlement in Box Valley

Fertile lowlands, like Box Valley, were never abandoned as places of domestic residence and farming activity, even in periods of conflicting ownership, seen earlier.[5] Even in times of conflict between West Saxon, Mercian and Romano-British lordship, it would have been in the interest of new overlords to leave the existing settlements intact which might extract a higher tribute than starting anew. From around the mid-600s, there is evidence of the growing prominence of enclosures and boundaries in Wiltshire, then of droveways which linked settlements to arable expansion.

There is possible evidence of Anglo-Saxon investment in the Box area. The introduction of hay meadows was one aspect of a growing investment in the countryside by elite families and organisations, including ecclesiastical foundations. They were what we might now think of as capitals projects, such as watermills which are dealt with below.

Fertile lowlands, like Box Valley, were never abandoned as places of domestic residence and farming activity, even in periods of conflicting ownership, seen earlier.[5] Even in times of conflict between West Saxon, Mercian and Romano-British lordship, it would have been in the interest of new overlords to leave the existing settlements intact which might extract a higher tribute than starting anew. From around the mid-600s, there is evidence of the growing prominence of enclosures and boundaries in Wiltshire, then of droveways which linked settlements to arable expansion.

There is possible evidence of Anglo-Saxon investment in the Box area. The introduction of hay meadows was one aspect of a growing investment in the countryside by elite families and organisations, including ecclesiastical foundations. They were what we might now think of as capitals projects, such as watermills which are dealt with below.

|

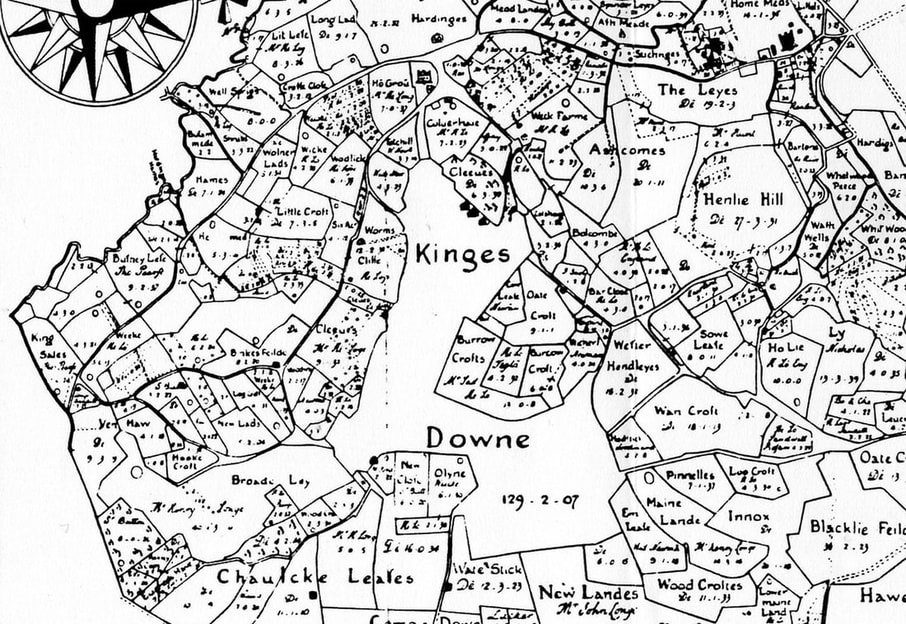

Evidence of occupation can be seen in the use of the word hãm (homestead) such as Fogham on the banks of the By Brook. It is believed that the lowland areas were used for their meadows to provide winter feed for sheep and cattle grazed on the surrounding hills and as secure enclosure for prized and pregnant animals.[6] We see this pattern of usage in the Allen maps of 1630 with a large number of fields referred to as mæd (meadow), especially around the By Brook in the centre of the village such as Hill Meade, Little Me(ad), Brode Mea(d), Kings M(ead) and Mead Lande. There are also a number of composite words using a "mead" suffix, including Ash Meade, Slade mead, yoles mead and Ven Meade.

|

-æker = acre of ploughed land -dun = hill -feld = open land -graf = grove/ copse -hãm = homestead -lëah = wood/ clearing -mæd = meadow |

The valley slopes were often used for arable farming with names of land and æker (acre) referring to ploughed land. There are several field-name references in Allen’s map to the enclosure of land, many with reference to the size of fields. These include Six Acr (e) Kingsdown, Ni(n)e Acre near Chapel Plaister, Twelve acres Hazelbury and Ash acres Rudloe. We can’t positively date them to the early or middle Saxon period (rather than later medieval) but the longevity of field-names is commonplace.

Pattern of Occupation

Some authorities have claimed that there may have been a distinctive pattern to the Saxon layouts with a sophisticated land infrastructure surrounding the domestic buildings.[7] Radiating from the centre, the characteristic pattern of the rings of land was proposed as:

Some authorities have claimed that there may have been a distinctive pattern to the Saxon layouts with a sophisticated land infrastructure surrounding the domestic buildings.[7] Radiating from the centre, the characteristic pattern of the rings of land was proposed as:

- closes (for gardens, bee hives), paddocks (for animal breeding and over-wintering);

- arable land (for growing cereals and legumes), pasture (for cattle, sheep and horses), meadows (for hay for winter fodder and low-lying meadows for early hay);

- common land and wasteland (for daily fuel, and wild animals as food); and

- cultivated woodland (pollarded for building materials and used also for pasture of pigs).[8]

Some of this occurs in the Box landscape but this concept appears to be a theoretical model, perhaps based on common sense, more than a standard layout. The actualities of the opportunities and constraints offered by particular topographies mean that such patterns are actually hard to discern in reality, even if they do give some indication of the needs of farming at this time. The pattern of land holding in Box might be more relevant to topographical features. The river was the industrial area with watermills at Drewetts, Box and Cuttings. In the Domesday Book, none are named and they have only been associated anecdotally. The first two were referenced: 2 mills which pay 35s held by Rainald (Croke) under the lands of Milo (Crispin). Cuttings Mill is believed to have been demolished by the Railway line and Railway Station). It was called half mill which pays 5s held by Warner from King William and the other half (on the opposite bank?) was possible held directly by the king.

One vital component for a self-sufficient community was woodland, needed every day for cooking, heating, small tools and building purposes. In Box, woodland appears to have run in a continuous line from the edge of village pasture land, uphill to Henley, east to Hatt and past Hazelbury. Today these woods have been encroached upon and divided by the A365 into sections called Thorn Wood, White Wood and Privetts Wood. The words lëah (area where woods have been cleared), feld (open land, several) and graf (grove/copse) feature in Box’s field-names indicating the importance of woodland or cleared woodland in the area. There are several whole areas with the lëah suffix including Ashley and Henley and even more references outside the village at Farleigh, Leigh, Winsley, Woolley and similar. Some lëah words describe the early use of cleared fields, including Swine Leyes, Hawe Leies, and Holleleyes. Other names describe of the size of the area such as Broade Ley and Multö Ley. Feld is an interesting word which has been suggested as land cleared of woodland/scrub in contrast to nearby woods, a juxtaposition which still dominates Box’s landscape.[11]

Some 1630 Box field-names with the word feld reflect the earlier use of these cleared areas. Some appear to be enclosed out of the common field system running down to the By Brook, Feilde Close and Darley Hill Feilde; some refer to use of the area,

Stey Feilde (pigs) and Tile Pitte Feilde (building material). The use of grove is seen in Ashley where the field next to Ashley Manor is called Hö Groü (Hay Grove).

One vital component for a self-sufficient community was woodland, needed every day for cooking, heating, small tools and building purposes. In Box, woodland appears to have run in a continuous line from the edge of village pasture land, uphill to Henley, east to Hatt and past Hazelbury. Today these woods have been encroached upon and divided by the A365 into sections called Thorn Wood, White Wood and Privetts Wood. The words lëah (area where woods have been cleared), feld (open land, several) and graf (grove/copse) feature in Box’s field-names indicating the importance of woodland or cleared woodland in the area. There are several whole areas with the lëah suffix including Ashley and Henley and even more references outside the village at Farleigh, Leigh, Winsley, Woolley and similar. Some lëah words describe the early use of cleared fields, including Swine Leyes, Hawe Leies, and Holleleyes. Other names describe of the size of the area such as Broade Ley and Multö Ley. Feld is an interesting word which has been suggested as land cleared of woodland/scrub in contrast to nearby woods, a juxtaposition which still dominates Box’s landscape.[11]

Some 1630 Box field-names with the word feld reflect the earlier use of these cleared areas. Some appear to be enclosed out of the common field system running down to the By Brook, Feilde Close and Darley Hill Feilde; some refer to use of the area,

Stey Feilde (pigs) and Tile Pitte Feilde (building material). The use of grove is seen in Ashley where the field next to Ashley Manor is called Hö Groü (Hay Grove).

Unlikely Continuity of Place-names

Many of the present names in Box preserve historic connotations but suggestions that they were continuously so named for millennia is unlikely. The Townsend area was the extremity of a later village, the name referring to land situated between the village houses and common fields, often left free from planting.[9] Bull Lane is a modern name but it could have been a track leading into a field where valuable breeding animals were kept separate from common grazing areas within easy reach of assistance and for feeding over winter.[10] There are numerous references to "close" in Box, in fact so many that their ubiquity makes dating impossible but enclosure of areas was probably sixteenth or seventeenth century. There are also many references to "croft" in certain locations such as Kingsdown, meaning a small, tenanted field with a house, again of uncertain provenance.

Many of the present names in Box preserve historic connotations but suggestions that they were continuously so named for millennia is unlikely. The Townsend area was the extremity of a later village, the name referring to land situated between the village houses and common fields, often left free from planting.[9] Bull Lane is a modern name but it could have been a track leading into a field where valuable breeding animals were kept separate from common grazing areas within easy reach of assistance and for feeding over winter.[10] There are numerous references to "close" in Box, in fact so many that their ubiquity makes dating impossible but enclosure of areas was probably sixteenth or seventeenth century. There are also many references to "croft" in certain locations such as Kingsdown, meaning a small, tenanted field with a house, again of uncertain provenance.

Conclusion

Field-name and place-name evidence seems to suggest that Anglo-Saxon settlements existed throughout the Box area, not just in the central location. Even though they were centuries later, we are fortunate to have the detailed descriptions of our area in the Allen maps. From these we might surmise that isolated farmstead settlements existed in the hamlets such as Ashley, Middlehill, Hazelbury and Rudloe. Certainly, there was abundant spring water throughout the area (not just the Lid and By Brooks), which enabled farming and residential occupation of the hamlets.[12] We consider these in more detail in a later issue.

Field-name and place-name evidence seems to suggest that Anglo-Saxon settlements existed throughout the Box area, not just in the central location. Even though they were centuries later, we are fortunate to have the detailed descriptions of our area in the Allen maps. From these we might surmise that isolated farmstead settlements existed in the hamlets such as Ashley, Middlehill, Hazelbury and Rudloe. Certainly, there was abundant spring water throughout the area (not just the Lid and By Brooks), which enabled farming and residential occupation of the hamlets.[12] We consider these in more detail in a later issue.

References

[1] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.74

[2] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.78

[3] See https://www.archiuk.com/cgi-bin/web-archi.pl?PlacenameFromPlacenameFinder=Chippenham&CountyFromPlacenameFinder=Wiltshire&distance=10000&ARCHIFormNGRLetter=ST&ARCHIFormNGR_x=91&ARCHIFormNGR_y=73&info2search4=placename_search&[email protected]#anglo-saxon

[4] Bruce Eagles, Roman Wiltshire and After (editor Peter Ellis), 2001, “Anglo-Saxon Presence and Culture in Wiltshire, AD 450-c675”, p.222

[5] Francis Pryor, The Making of the British Landscape, 2010, Penguin Books, p.218

[6] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.147

[7] Michael Aston, Interpreting the Landscape, 1985, BT Batsford, p.98

[8] Michael Aston, Interpreting the Landscape, p.103

[9] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.150

[10] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.126

[11] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.149

[12] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.163

[1] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.74

[2] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.78

[3] See https://www.archiuk.com/cgi-bin/web-archi.pl?PlacenameFromPlacenameFinder=Chippenham&CountyFromPlacenameFinder=Wiltshire&distance=10000&ARCHIFormNGRLetter=ST&ARCHIFormNGR_x=91&ARCHIFormNGR_y=73&info2search4=placename_search&[email protected]#anglo-saxon

[4] Bruce Eagles, Roman Wiltshire and After (editor Peter Ellis), 2001, “Anglo-Saxon Presence and Culture in Wiltshire, AD 450-c675”, p.222

[5] Francis Pryor, The Making of the British Landscape, 2010, Penguin Books, p.218

[6] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.147

[7] Michael Aston, Interpreting the Landscape, 1985, BT Batsford, p.98

[8] Michael Aston, Interpreting the Landscape, p.103

[9] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.150

[10] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.126

[11] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.149

[12] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.163