The Woman Who Loved Mummies: Rachel Amelia Lee (nee Oldroyd)

Research Contributed by Emma Simpson March 2019

Research Contributed by Emma Simpson March 2019

The well-known BBC presenter, Samira Ahmed, recently looked at female influences on the discovery and collection of Egyptian mummies in a programme on Radio 3.[1] One of these women, Rachel Amelia Lee (nee Oldroyd) lived at Spa House, Box, in the 1930s and died there on 22 July 1932, aged 74. She was an intrepid Victorian explorer who helped bring ancient Egyptian artefacts back to the people of Dewsbury, artefacts that are now in the collections of Kirklees Museums and Galleries.

Katina Bill is Head Curator at Kirklees Museums & Galleries and has worked with Dr Margaret Serpico, a consultant Egyptologist who has worked in Egyptology collections in England and co-curated the Beyond Beauty exhibition in London, to better understand items in the Kirklees Collection and uncover details of the life of Ms Oldroyd.

Katina Bill is Head Curator at Kirklees Museums & Galleries and has worked with Dr Margaret Serpico, a consultant Egyptologist who has worked in Egyptology collections in England and co-curated the Beyond Beauty exhibition in London, to better understand items in the Kirklees Collection and uncover details of the life of Ms Oldroyd.

|

Oldroyd Family

Amelia wasn’t local to Box, Wiltshire. She was born at Hanging Heaton, Soothill, Dewsbury, Yorkshire, in 1858 second daughter of George Oldroyd and Elizabeth Oates. The family were mill owners and Amelia’s grandfather Mark Oldroyd ran a cloth manufacturing business employing 30 men in Dewsbury in 1851. Amelia’s father George expanded the Sprinkwell Mill and the family became extremely wealthy in the years of Victorian economic boom. George’s death in 1876 was recorded in the Dewsbury Reporter in the most glowing terms: George Oldroyd, Esq, was a hand-loom weaver in his early years and by his diligence and a remarkable aptitude for business he, his father and his brother John succeeded in raising themselves to a position of great affluence, establishing the firm of M Oldroyd and Sons, the largest of its kind in the world.[2] During the funeral service, the firm did a most unusual thing, the mills of the firm M Oldroyd and Sons ceased to run and a large number of operatives assembled (to pay their respects) within the building. The Oldroyds were one of the many wealthy families in the Dewsbury area. Amelia’s uncle Sir Mark Oldroyd was also a mill owner and Dewsbury Member of Parliament, who lived at Hyrstlands, Batley, a Grade II listed building, built by him in 1891. |

Dr Edwin Lee

Amelia’s husband, Edwin Lee, was a renowned local doctor, a member of the Royal College of Surgeons, England General Practitioners by the age of 28 in 1881. Edwin and Amelia married at Dewsbury in 1899 when he was 46 and she was 41, their first marriage and neither had any children. They lived at 24 Halifax Road in 1901 with three servants including a French maid and were on the same street in 1911 in Broomfield House, possibly the same house renamed. Edwin moved in important local circles and was later remembered by James Seaton, Bishop of Wakefield, as a very true friend to many. The bishop recalled that when he attended the doctor as a young boy, Bishop Seaton learned his way around the streets of Dewsbury traversing them in a hansom cab.[3]

Edwin was too old for active service in the First World War but he appears to have volunteered as an officer probably assisting the recuperation of injured servicemen. He was given an officer’s award of the Voluntary Officer’s Decoration and used the title Colonel.[4]

Egypt Exploration Fund

Amelia took full advantage of the opportunities her background afforded her, for both personal and public benefit. It used to be thought that Amelia played a largely administrative role in fundraising for the discovery of artefacts as the local honorary Secretary for the Egypt Exploration Fund, Dewsbury Branch.[5] She personally donated contributions to the Fund both before and after her marriage and persuaded her siblings to do so. Her contemporary obituary said simply She was greatly interested in Egyptology and, as a result of her efforts in obtaining subscribers to the Egypt Exploration Fund, Mrs Lee was responsible for obtaining the valuable collection of Egyptian relics in the museum in Crow Nest Park, Dewsbury.[6]

The Fund was founded in London in 1882 to explore, survey, and excavate in Egypt. Its main purpose was to produce publications and lectures but it was licenced to export a portion of discoveries and there is no doubt that the collections of artefacts in British museums was part of its aim. We nowadays regard this as tantamount to looting but, at the time, it was regarded as an attempt to conserve antiquities in public hands and make them accessible to view. Many wealthy mill-owning daughters and wives were caught up with enthusiasm to support the Fund and it is alleged that they were the main instrument in saving textiles and other intimate small portable objects.[7]

Amelia’s husband, Edwin Lee, was a renowned local doctor, a member of the Royal College of Surgeons, England General Practitioners by the age of 28 in 1881. Edwin and Amelia married at Dewsbury in 1899 when he was 46 and she was 41, their first marriage and neither had any children. They lived at 24 Halifax Road in 1901 with three servants including a French maid and were on the same street in 1911 in Broomfield House, possibly the same house renamed. Edwin moved in important local circles and was later remembered by James Seaton, Bishop of Wakefield, as a very true friend to many. The bishop recalled that when he attended the doctor as a young boy, Bishop Seaton learned his way around the streets of Dewsbury traversing them in a hansom cab.[3]

Edwin was too old for active service in the First World War but he appears to have volunteered as an officer probably assisting the recuperation of injured servicemen. He was given an officer’s award of the Voluntary Officer’s Decoration and used the title Colonel.[4]

Egypt Exploration Fund

Amelia took full advantage of the opportunities her background afforded her, for both personal and public benefit. It used to be thought that Amelia played a largely administrative role in fundraising for the discovery of artefacts as the local honorary Secretary for the Egypt Exploration Fund, Dewsbury Branch.[5] She personally donated contributions to the Fund both before and after her marriage and persuaded her siblings to do so. Her contemporary obituary said simply She was greatly interested in Egyptology and, as a result of her efforts in obtaining subscribers to the Egypt Exploration Fund, Mrs Lee was responsible for obtaining the valuable collection of Egyptian relics in the museum in Crow Nest Park, Dewsbury.[6]

The Fund was founded in London in 1882 to explore, survey, and excavate in Egypt. Its main purpose was to produce publications and lectures but it was licenced to export a portion of discoveries and there is no doubt that the collections of artefacts in British museums was part of its aim. We nowadays regard this as tantamount to looting but, at the time, it was regarded as an attempt to conserve antiquities in public hands and make them accessible to view. Many wealthy mill-owning daughters and wives were caught up with enthusiasm to support the Fund and it is alleged that they were the main instrument in saving textiles and other intimate small portable objects.[7]

New Discoveries about Amelia’s Egyptology Work

But her administrative work was only part of her efforts and I love the fact it’s now confirmed she went to the tomb in Egypt to assist the work of the eminent archaeologist Sir William Flinders Petrie, sometimes called the father of scientific archaeology! There was a deep connection with the Fund as, from the outset of his career, the Fund supported him financially and approved his appointment as Professor of Egyptology, University of Central London.

Amelia went to visit the Nile and the antiquities with a relative in 1892 and joined up with Petrie and his wife Hilda at the extensive archaeological site at Amarna, Egypt.[8] In his autobiography Petrie records the visits of his friend Amelia:[9]

Amelia Oldroyd, with her nephew Borwick, stayed for ten days.

Miss Oldroyd and Borwick followed as soon as there was room for them and stayed long enough to see the first tombs opened.

For nearly a month she [Hilda] kept to her bed with a fever; she ate little, and Miss Oldroyd, arriving on her usual visit, stayed on to nurse her and to tempt her appetite with little dishes.

The intrepid Miss Oldroyd and nephew would be staying for a time.

But her administrative work was only part of her efforts and I love the fact it’s now confirmed she went to the tomb in Egypt to assist the work of the eminent archaeologist Sir William Flinders Petrie, sometimes called the father of scientific archaeology! There was a deep connection with the Fund as, from the outset of his career, the Fund supported him financially and approved his appointment as Professor of Egyptology, University of Central London.

Amelia went to visit the Nile and the antiquities with a relative in 1892 and joined up with Petrie and his wife Hilda at the extensive archaeological site at Amarna, Egypt.[8] In his autobiography Petrie records the visits of his friend Amelia:[9]

Amelia Oldroyd, with her nephew Borwick, stayed for ten days.

Miss Oldroyd and Borwick followed as soon as there was room for them and stayed long enough to see the first tombs opened.

For nearly a month she [Hilda] kept to her bed with a fever; she ate little, and Miss Oldroyd, arriving on her usual visit, stayed on to nurse her and to tempt her appetite with little dishes.

The intrepid Miss Oldroyd and nephew would be staying for a time.

Amelia’s Collection of Artefacts

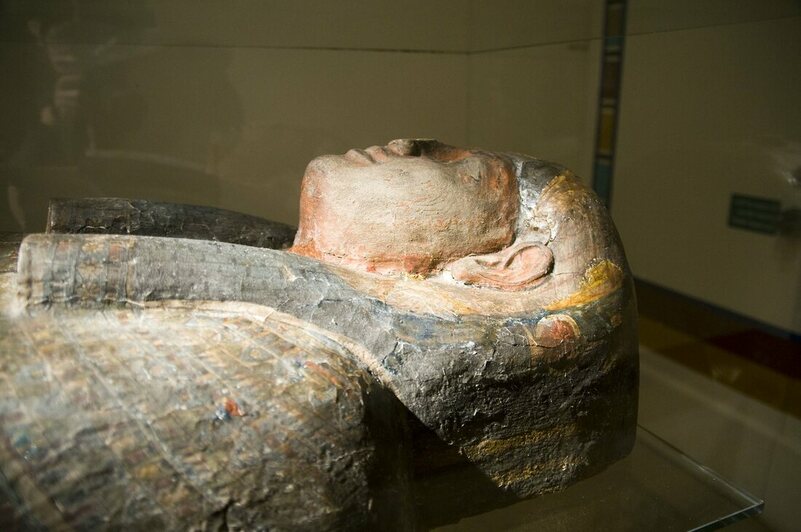

Amelia arranged for hundreds of Egyptian artefacts to be sent to the Dewsbury Museum where they were held for many years until transfer to the Bagshaw Museum in Batley. She recorded her finds in leather-bound catalogues in the archive of the Bagshaw Museum. She was one of the first to explore a burial chamber at Abydos and this has now been recreated in the museum.

Many of the exhibits are mummy wrappings, tapestries and textiles, which presumably Amelia was interested in and knowledgeable about. There are also some fascinating cartonnages (funerary masks) made of linen and papyrus and decorated in sumptuous blue, red and gold.

Amelia arranged for hundreds of Egyptian artefacts to be sent to the Dewsbury Museum where they were held for many years until transfer to the Bagshaw Museum in Batley. She recorded her finds in leather-bound catalogues in the archive of the Bagshaw Museum. She was one of the first to explore a burial chamber at Abydos and this has now been recreated in the museum.

Many of the exhibits are mummy wrappings, tapestries and textiles, which presumably Amelia was interested in and knowledgeable about. There are also some fascinating cartonnages (funerary masks) made of linen and papyrus and decorated in sumptuous blue, red and gold.

Exhibits in Bagshaw Museum, Batley (courtesy Kirklees Council)

Conclusion

On Amelia’s death, most of her estate of £14, 551 was left to her nephews and nieces, Geoffrey and Margaret Inman and Hilda Mary Swift but she also left £500 to my faithful friend and cook Elizabeth Jenks, £300 to my kind maid Isabel Simpson and £200 to Tom Lever manservant.[10]

Kirklees curator, Katina Bill, said We owe a great debt to Amelia and her work to bring Egyptian artefacts to her home town. Without her, Bagshaw Museum would not have its stunning Kingdom of Osiris gallery filled with mummy masks, Egyptian jewellery and mystical amulets which have been enjoyed by generations of local people.

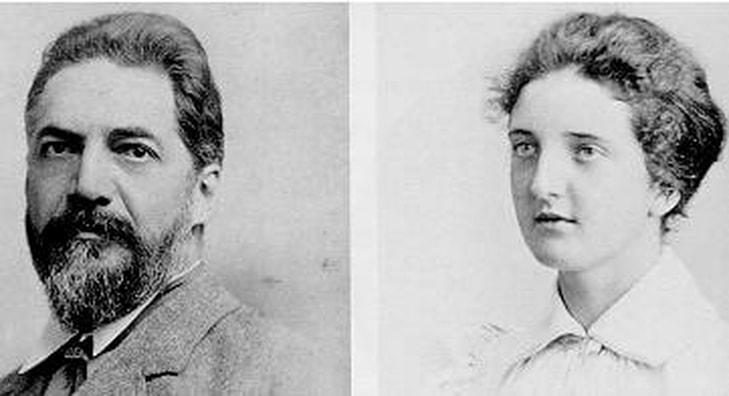

I am thrilled when an aspect of history (often the role of women) emerges out of the historic fog and challenges all our concepts about the story. In case you were hoping for a photograph of Amelia or Edwin, I haven’t been able to find one. Is there anybody out there who can help please?

Family Tree

George Oldroyd (1824 – 1876 or 1889) married Elizabeth Oates (1828 - 1903) at Dewsbury in 1853. They lived in some style at Stony Hurst, Track Road, Batley, Dewsbury from at least 1871, when George had made enough money to retire age 47. In 1881 they had a cook, two housemaids and a domestic page. Elizabeth was still there in 1901 with four servants. Children:

Ellen Elizabeth (b 1854); George Henry (b 1857); Rachel Amelia (1858 – 22 July 1932); Sarah Louie (b 1861); and Mary Adelaide (b 1862).

Rachel Amelia married Dr Edwin Lee (b 1853) at Dewsbury in 1899.

On Amelia’s death, most of her estate of £14, 551 was left to her nephews and nieces, Geoffrey and Margaret Inman and Hilda Mary Swift but she also left £500 to my faithful friend and cook Elizabeth Jenks, £300 to my kind maid Isabel Simpson and £200 to Tom Lever manservant.[10]

Kirklees curator, Katina Bill, said We owe a great debt to Amelia and her work to bring Egyptian artefacts to her home town. Without her, Bagshaw Museum would not have its stunning Kingdom of Osiris gallery filled with mummy masks, Egyptian jewellery and mystical amulets which have been enjoyed by generations of local people.

I am thrilled when an aspect of history (often the role of women) emerges out of the historic fog and challenges all our concepts about the story. In case you were hoping for a photograph of Amelia or Edwin, I haven’t been able to find one. Is there anybody out there who can help please?

Family Tree

George Oldroyd (1824 – 1876 or 1889) married Elizabeth Oates (1828 - 1903) at Dewsbury in 1853. They lived in some style at Stony Hurst, Track Road, Batley, Dewsbury from at least 1871, when George had made enough money to retire age 47. In 1881 they had a cook, two housemaids and a domestic page. Elizabeth was still there in 1901 with four servants. Children:

Ellen Elizabeth (b 1854); George Henry (b 1857); Rachel Amelia (1858 – 22 July 1932); Sarah Louie (b 1861); and Mary Adelaide (b 1862).

Rachel Amelia married Dr Edwin Lee (b 1853) at Dewsbury in 1899.

References

[1] Samira Ahmed, The Victorian Queens of Ancient Egypt, 3 February 2019, BBC Radio 3 and https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/stories-47093041

[2] Dewsbury Reporter, 26 August 1876

[3] The Leeds Mercury, 28 October 1937

[4] Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 23 July 1932

[5] Report of the Twelfth Ordinary General Meeting of the Egypt Exploration Fund, 1897-98

[6] The Yorkshire Post, 23 July 1932

[7] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/stories-47093041

[8] London Evening Standard, 30 June 1897

[9] Flinders Petrie, A life in Archaeology, 1985, Victor Gollancz, p219, 228, 245 and 226

[10] Bath & Chronicle Weekly Gazette, 19 November 1932; The Yorkshire Post, 14 November 1932 and Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 14 November 1932

[1] Samira Ahmed, The Victorian Queens of Ancient Egypt, 3 February 2019, BBC Radio 3 and https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/stories-47093041

[2] Dewsbury Reporter, 26 August 1876

[3] The Leeds Mercury, 28 October 1937

[4] Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 23 July 1932

[5] Report of the Twelfth Ordinary General Meeting of the Egypt Exploration Fund, 1897-98

[6] The Yorkshire Post, 23 July 1932

[7] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/stories-47093041

[8] London Evening Standard, 30 June 1897

[9] Flinders Petrie, A life in Archaeology, 1985, Victor Gollancz, p219, 228, 245 and 226

[10] Bath & Chronicle Weekly Gazette, 19 November 1932; The Yorkshire Post, 14 November 1932 and Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 14 November 1932