|

Aircraft Factories Underground: Places which must be Nameless Alan Payne February 2018 Nowadays we might belittle the wartime slogan Careless Talk Costs Lives but the wartime government was terrified of the effect that adverse or scare-mongering stories could have on public morale. The Bath Chronicle of January 1940 revealed that The weather in War-time is a hush-hush topic for fear of revealing information to the enemy.[1] It could only be revealed a fortnight after the actual date. |

State Censorship

Military set-backs had to be minimised; the location of factories, traffic diversions and public events referred to in obscure terms; and, worst of all, reference to children or husbands serving abroad totally excluded. What is perhaps less well-known is the detail of control that the war brought to the domestic population, particularly control of news and the media.

Because the newspapers could publish little information, they turned to patriotic events in the past. The Bath Chronicle ran a series on How Bath Prepared for Napoleon in March 1942, including instructions on destroying livestock to reduce the enemy's supplies and making flour for storage for domestic use.[2] Clearly the article was veiled advice in the event of a Nazi invasion.

Military set-backs had to be minimised; the location of factories, traffic diversions and public events referred to in obscure terms; and, worst of all, reference to children or husbands serving abroad totally excluded. What is perhaps less well-known is the detail of control that the war brought to the domestic population, particularly control of news and the media.

Because the newspapers could publish little information, they turned to patriotic events in the past. The Bath Chronicle ran a series on How Bath Prepared for Napoleon in March 1942, including instructions on destroying livestock to reduce the enemy's supplies and making flour for storage for domestic use.[2] Clearly the article was veiled advice in the event of a Nazi invasion.

Underground Factories

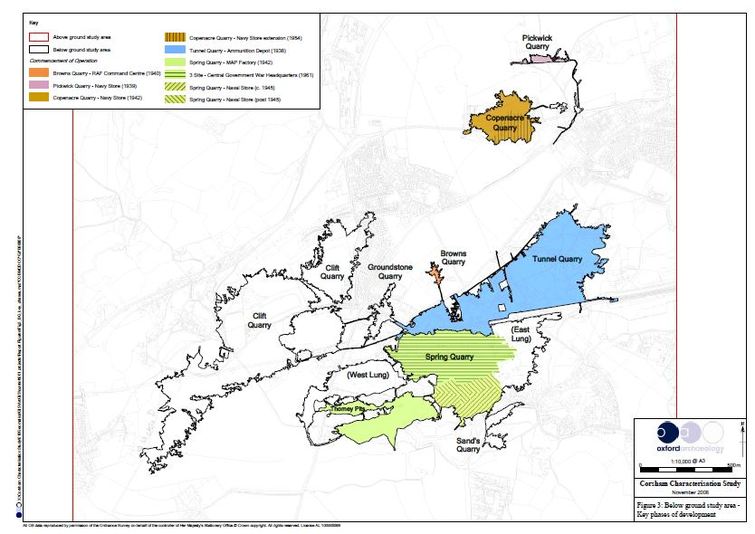

German bombing raids on Bristol in September 1940, which killed 160 workers, convinced the Ministry of Aircraft Production to make dramatic changes in Britain's manufacturing facilities.[3] Suddenly on 7 December 1940 the Ministry requisitioned various quarries still being worked by the Bath and Portland Company, mainly Spring Quarry. The move surprised the workers, who dropped their tools where they had been working and abandoned lamps, saws, half-cut blocks of stone and lifting cranes.

German bombing raids on Bristol in September 1940, which killed 160 workers, convinced the Ministry of Aircraft Production to make dramatic changes in Britain's manufacturing facilities.[3] Suddenly on 7 December 1940 the Ministry requisitioned various quarries still being worked by the Bath and Portland Company, mainly Spring Quarry. The move surprised the workers, who dropped their tools where they had been working and abandoned lamps, saws, half-cut blocks of stone and lifting cranes.

|

The Ministry intended to move vital, military production factories into safer underground locations. Their costings estimated an investment cost of £100,000 and a completion time of six months.[4]

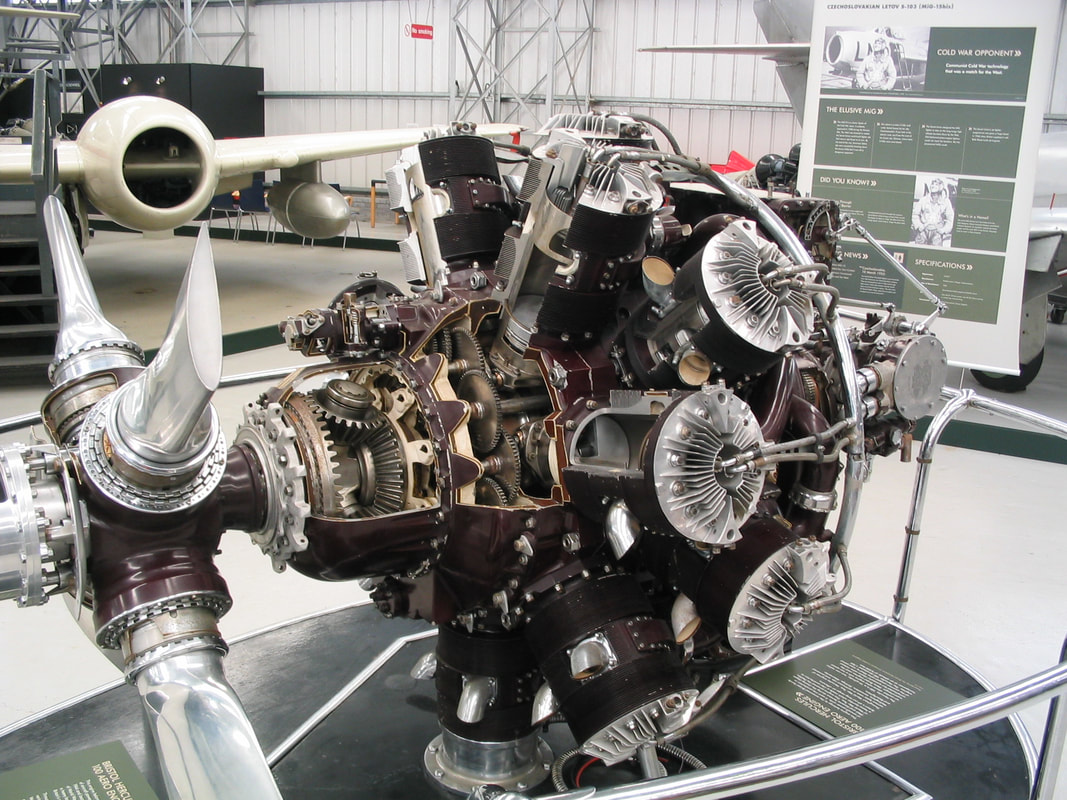

The original plan was to move the Bristol Aeroplane Company's Hercules Bomber engine plant from Filton, together with Parnell's gun turret facilities from Yate, Bristol, and the Dowty Company's undercarriage plant at Gloucester. The Spring Quarry was chosen because of its 55 acres of underground tunnels. McAlpine, the clearance contractors, recruited 10,000 navvies mostly from the Irish Republic.[5] Left: The Hercules engine (courtesy Wikipedia) |

Work started in April 1941 but, far from a quick job, the scheme expanded beyond recognition. To move the anticipated workers quickly two escalators were removed from Underground Tube Stations at Holborn and St Paul's, and four large, passenger lifts installed.[6] Wide roadways were made connecting different workshops, stores and rest facilities.[7] Being entirely underground enormous ventilation systems were needed (sealed to prevent attack by poison gas), special lighting, compressors, boiler houses for heating and power and an entirely new Telephone Exchange called Hawthorn. The work was plagued by delays and cost over-runs and the eventual cost was reputed to be £19 million.[8] Reduced German air strikes resulted in Parnells and Dowty declining to take up space. BAC left the Hercules engines in Filton and took up only a portion of their allotted area to develop experimental Centaurus engines.[9] Only part of the BAC area was taken up and the Birmingham Small Arms Company took up a small area to make cannon barrels and they were in operation for only about 18 months. In the end only 523 engines are believed to have been built underground.[10]

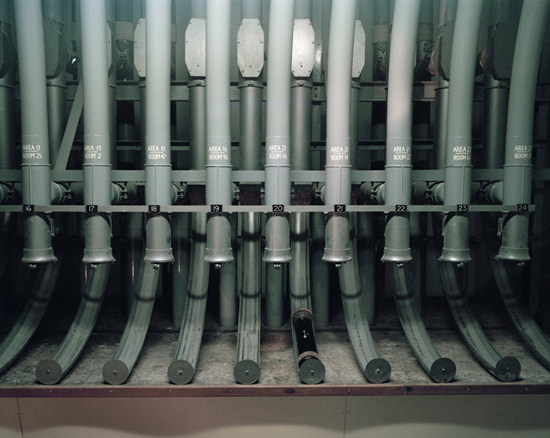

In the 1950s and 1960s the factories were converted into a governmental nuclear retreat called Burlington Bunker (photos courtesy Jason Orton)

In a remarkable development in 1943, a mural painter, Olga Lehmann, was commissioned to decorate the walls of the various canteens. She had already undertaken a number of civic works, including murals at the London Air Raid Precautions Headquarters in 1940, air raid shelters, and the Censorship Department, Holborn, in 1942. The walls at Springfields have remains of her work showing friezes of pre-historic animals, African scenes and horse-riders.[11]

In 1943, other quarries were taken over for military purposes. Brown's Quarry was converted into a command centre for RAF Fighter Command including an operations room and plotting table.[12] It is alleged that the Cabinet Office would be sited in the Box Tunnels in the event that the Germans invaded and overran London. The work left changes that are still with us, mostly in the north-east of the parish, including the name Hawthorn, and the 18-inch gas mains pipe which runs from Bath to Corsham.[13]

Housing the Workers

Factory workers came from Bristol, miners from the North of England and Wales, and navvies from Ireland. A Catholic church was established at Leafield to cater for them, which in 1946 became a permanent location called St Patrick’s in the old Pickwick School (used as a gas mask factory during the war).[14]

The original plan was to house 14,000 workers with eight hostels at Rudloe and Corsham each housing 1,000 persons; 1,300 people in married quarters at Hawthorn; and the remainder bussed in from Bath.[15] The workers from Bristol refused to move and in the end only half of the houses were actually built.[16] Instead in 1942 prefabricated huts were put up in Corsham for Bristol workers made homeless by bombardment and these were subsequently redeveloped as council estates in the 1950s

and the 1960s.[17]

The number of buses had to be increased to get the workers from their accommodation in Bath and Box to the underground factories. In November 1940 the Bath Tramways Motor Company Limited notified travellers that these services would be increased but at the expense of stopping regular services half an hour earlier on weekdays and an hour on Sundays.[18]

By 1944 the movement of factory workers was so great that bus routes were introduced for them alone separating ordinary civilian travellers, number 50a three times daily in each direction between Bath, Box, Hawthorn, Corsham.[19] By the end of the war another group of servicemen were using public transport, the wounded soldiers trying to find a life in the civilian world.

In April the Bath Tramway Company allowed them to travel free of charge on their buses.[20]

Defending the Area

After 1940 Rudloe Manor became the headquarters of 10 Group Fighter Command.[21] From spring 1940 to May 1945 the Manor House controlled Allied planes in South West England and South Wales and investigated enemy activity.

An elaborate decoy system was built to confuse enemy bombers. At Norbin Barton Farm lights were installed to replicate those at Thingley Railway Junction and Farleigh Down sidings and a special bunker at Norbin Barton to house an electricity generator to simulate fires set off by bomb strikes.[22] Huge stone blocks were installed on Kingsdown Common to prevent enemy gliders landing and nearly 3,000 Home Guards deployed to man road blocks and checkpoints day and night in 1940.

The houses at Rudloe and Hawthorne were referred to in the most discreet terms, so that the Germans should not be aware of their existence. Almost the only contemporary reference in the Parish Magazine is in May 1943 that our congregations are supplemented by members of the Forces, and other civilians in the area. The area of concrete at Rudloe Industrial Estate is the last visible evidence of the hostels but the Hawthorn buildings remain in use.

In 1943, other quarries were taken over for military purposes. Brown's Quarry was converted into a command centre for RAF Fighter Command including an operations room and plotting table.[12] It is alleged that the Cabinet Office would be sited in the Box Tunnels in the event that the Germans invaded and overran London. The work left changes that are still with us, mostly in the north-east of the parish, including the name Hawthorn, and the 18-inch gas mains pipe which runs from Bath to Corsham.[13]

Housing the Workers

Factory workers came from Bristol, miners from the North of England and Wales, and navvies from Ireland. A Catholic church was established at Leafield to cater for them, which in 1946 became a permanent location called St Patrick’s in the old Pickwick School (used as a gas mask factory during the war).[14]

The original plan was to house 14,000 workers with eight hostels at Rudloe and Corsham each housing 1,000 persons; 1,300 people in married quarters at Hawthorn; and the remainder bussed in from Bath.[15] The workers from Bristol refused to move and in the end only half of the houses were actually built.[16] Instead in 1942 prefabricated huts were put up in Corsham for Bristol workers made homeless by bombardment and these were subsequently redeveloped as council estates in the 1950s

and the 1960s.[17]

The number of buses had to be increased to get the workers from their accommodation in Bath and Box to the underground factories. In November 1940 the Bath Tramways Motor Company Limited notified travellers that these services would be increased but at the expense of stopping regular services half an hour earlier on weekdays and an hour on Sundays.[18]

By 1944 the movement of factory workers was so great that bus routes were introduced for them alone separating ordinary civilian travellers, number 50a three times daily in each direction between Bath, Box, Hawthorn, Corsham.[19] By the end of the war another group of servicemen were using public transport, the wounded soldiers trying to find a life in the civilian world.

In April the Bath Tramway Company allowed them to travel free of charge on their buses.[20]

Defending the Area

After 1940 Rudloe Manor became the headquarters of 10 Group Fighter Command.[21] From spring 1940 to May 1945 the Manor House controlled Allied planes in South West England and South Wales and investigated enemy activity.

An elaborate decoy system was built to confuse enemy bombers. At Norbin Barton Farm lights were installed to replicate those at Thingley Railway Junction and Farleigh Down sidings and a special bunker at Norbin Barton to house an electricity generator to simulate fires set off by bomb strikes.[22] Huge stone blocks were installed on Kingsdown Common to prevent enemy gliders landing and nearly 3,000 Home Guards deployed to man road blocks and checkpoints day and night in 1940.

The houses at Rudloe and Hawthorne were referred to in the most discreet terms, so that the Germans should not be aware of their existence. Almost the only contemporary reference in the Parish Magazine is in May 1943 that our congregations are supplemented by members of the Forces, and other civilians in the area. The area of concrete at Rudloe Industrial Estate is the last visible evidence of the hostels but the Hawthorn buildings remain in use.

References

[1] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 3 February 1940

[2] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 21 March 1942

[3] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, 2010, Folly Books, p.12-13

[4] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.107

[5] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.156-8

[6] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.107

[7] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.120-127

[8] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.230-1

[9] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.107

[10] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.202

[11] There are some great photographs of her work in Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.128-133

[12] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.63

[13] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.186

[14] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, p.15 & 50

[15] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.160-4

[16] VCH, Vol IV, p.250 and NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.194-9

[17] CJ Hall, Corsham: An Illustrated History, 1983, pub CJ Hall, p.30

[18] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 16 November 1940

[19] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 19 February 1944

[20] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 21 April 1945

[21] Countryside Treasures, Wiltshire History Centre, p.27

[22] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.119-123

[1] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 3 February 1940

[2] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 21 March 1942

[3] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, 2010, Folly Books, p.12-13

[4] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.107

[5] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.156-8

[6] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.107

[7] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.120-127

[8] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.230-1

[9] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.107

[10] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.202

[11] There are some great photographs of her work in Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.128-133

[12] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.63

[13] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.186

[14] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, p.15 & 50

[15] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.160-4

[16] VCH, Vol IV, p.250 and NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.194-9

[17] CJ Hall, Corsham: An Illustrated History, 1983, pub CJ Hall, p.30

[18] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 16 November 1940

[19] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 19 February 1944

[20] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 21 April 1945

[21] Countryside Treasures, Wiltshire History Centre, p.27

[22] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.119-123