|

After the War

Alan Payne March 2018 Many things would never be the same again after the end of hostilities. The centre of the village shifted location. When the village assembled to hear the announcement of peace, it was at the Rec that they assembled, rather than the old Fete Field. Within a short time the old Fete Field, which had hosted royal Jubilees and celebrations galore, had been developed into Bargates housing estate.[1] And the new estates at Rudloe resulted in a permanent school and community at Box Highlands. |

In July 1944 vicar Maltin talked about a better education for children with facilities for advancement and the phrase Social Security is one of the great hopes of post-war days.[2] Life after the war was never as good as the imagination had foreseen. There was a flush of post-war marriages and the baby boomer generation followed shortly after. But the romance of peace depicted in the 1945 film Brief Encounter never lived up to expectation. Some British girls left to marry American or other Allies servicemen; quite a few returned disillusioned.

For some there was frustration that wages and employment were so poor, and taxation rose repeatedly. Finding normality was frustrated by years of post-war rationing and making-do. It is well expressed in the pathos of a newspaper article of February 1946, Who Is She? I assisted a (young lady) with her luggage (on the Bristol to London train). She was destined for the WAAF camp at Hawthorn, Corsham. She left the train at Box. I would very much like to meet her again if possible.[3] It seemed hopeless but, unbelievably, she read the notice and wrote a letter to the inquirer. We will never know what it said.[4]

For some there was frustration that wages and employment were so poor, and taxation rose repeatedly. Finding normality was frustrated by years of post-war rationing and making-do. It is well expressed in the pathos of a newspaper article of February 1946, Who Is She? I assisted a (young lady) with her luggage (on the Bristol to London train). She was destined for the WAAF camp at Hawthorn, Corsham. She left the train at Box. I would very much like to meet her again if possible.[3] It seemed hopeless but, unbelievably, she read the notice and wrote a letter to the inquirer. We will never know what it said.[4]

The results of the General Election on 5 July 1945 were deferred to allow the counting of the votes of overseas servicemen.

A fortnight later it was confirmed that Attlee's Labour Party had won and society moved on a different course with the introduction of the National Health Act, the nationalisation of the Coal Board, Electricity, Bank of England and the Railways.

Changes in Box

The village road system was never the same after the Second World War. The fete held on Fete Field was the last one ever after hundreds of years. The chairman of Box Parish Council, CWB Oatley, proposed that the field be donated to the village and converted into the site of a village hall, but it was not to be.[5] Instead the area was used for residential accommodation and Bargates was constructed in 1950.

Industry was subject to the most dramatic change from military production of arms and munitions to the needs of a post-war population. Moon Aircraft Limited at the Clift Works on Box Hill sought both products and skilled people.[6] The company was wholly owned by the Bath and Portland Stone Firms Limited who had employed their skilled stone masons to make precision plastic mouldings and cockpits for military aircraft.[7] They were the Industry of the Future in 1945, manufacturing peace-time goods out of the newly-discovered perspex into shades for electric lights, soap-trays, fruit bowls and similar with the plastic which, worked like wood, could be turned, sawn, filed and polished.

The Stone Firms never recovered and their demise was swift after the war; their plastics venture never succeeded. By August 1946 a strike of fifty quarrymen at Hawthorn, Pickwick and Box Hill was officially recognised by Transport and General Workers' Union.[8] It was a dispute about wages differentials between unskilled labourers and the stone sawyers wanting an extra 2d per hour. The old order had shifted from piece-rates and the ganger system.

There were changes of personnel also and vicar AF Maltin was replaced by Rev Kenneth Crawford Scott in September 1945.[9]

Equally significant that month was the death of Maisie Gay, announced with the words that she had taken Her Final Curtain at her home at Whirligig, Kingsdown, aged 67.[10] She had run the Northey Arms from 1933 to 1936 and lived in Box ever since, although she was unable to get out much and was bed-ridden for a number of years.

CB Cochran gave his epitaph that in her genre, Maisie was unique and irreplaceable. [11] He had not been able to find anyone since her retirement who was such a wonderful character-drawer. He added a very moving tribute to her that She built a small house at Box and had been in bed ever since she went there. She had periods of unconsciousness and on one occasion when I visited her she wandered right back to her theatre days and said, "Don't worry, Mr Cochran, I shall be ready in time. Her words echoed the sentiment of most Box people during World War 2.

Troop Demobilisation

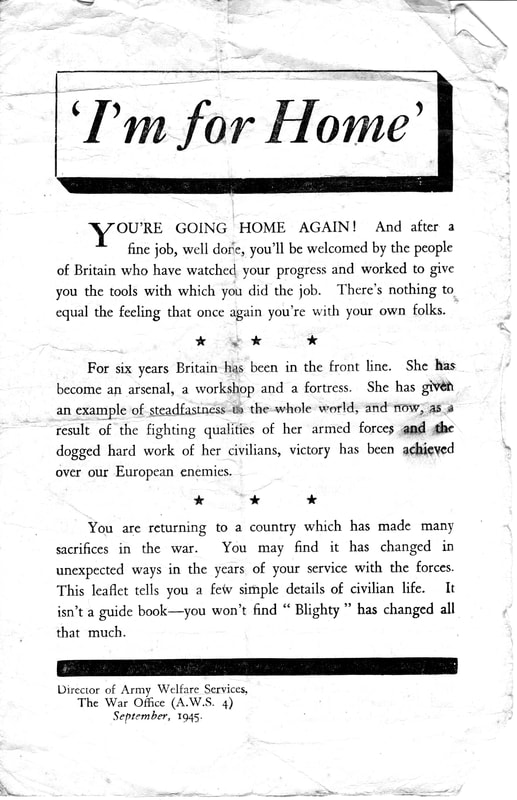

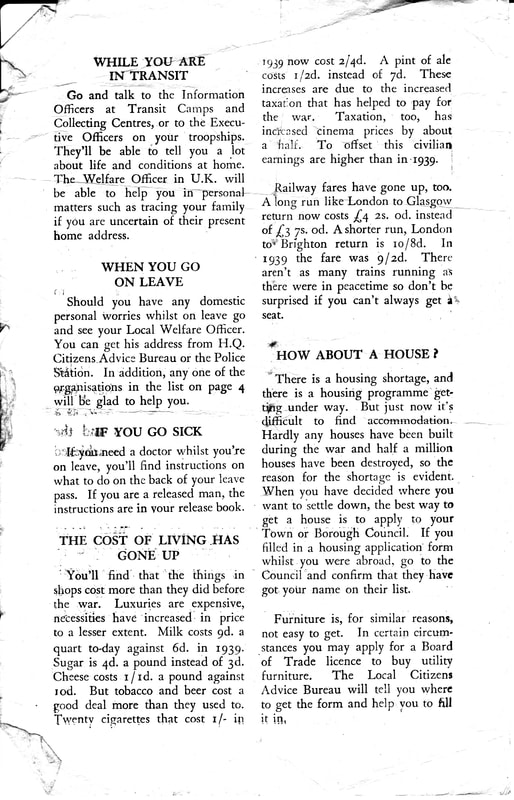

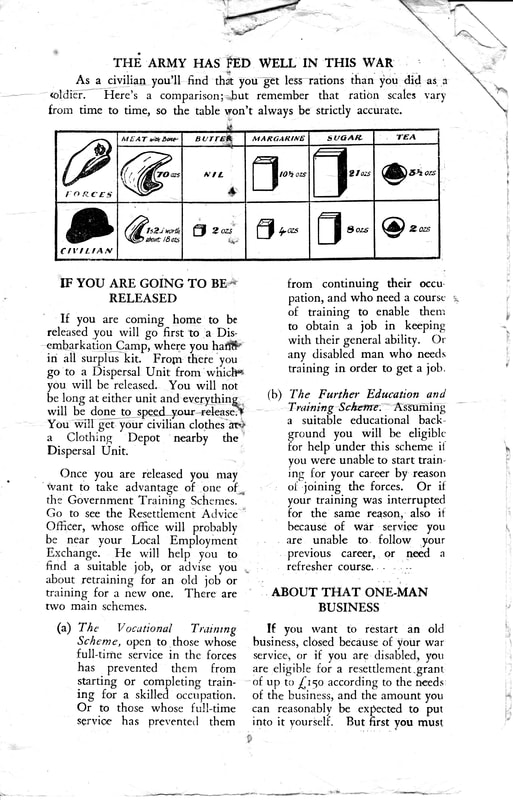

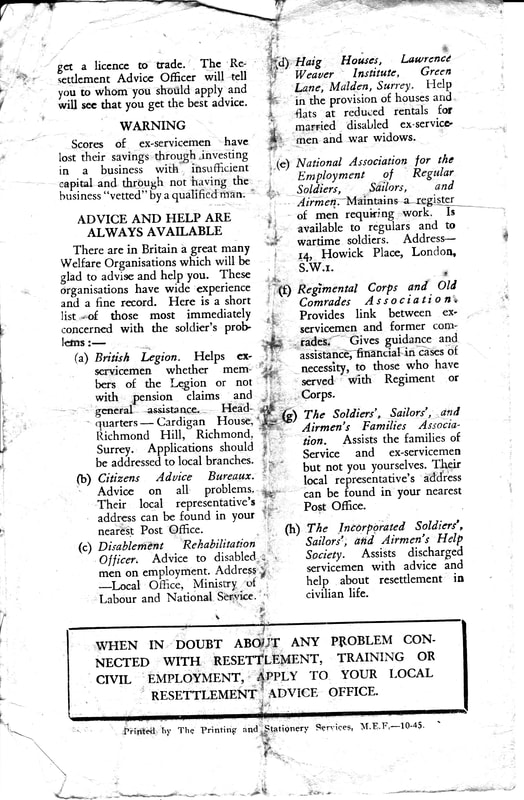

The troops returned many months after the end of hostilities. Prisoners-of-war were able to write freely but many had been listed as missing and were uncertain whether their families had believed them dead. The government issued instructions (such as the well-thumbed leaflet below courtesy Margaret Wakefield), which possibly added to the anxiety rather than proving a reassurance servicemen and women.

A fortnight later it was confirmed that Attlee's Labour Party had won and society moved on a different course with the introduction of the National Health Act, the nationalisation of the Coal Board, Electricity, Bank of England and the Railways.

Changes in Box

The village road system was never the same after the Second World War. The fete held on Fete Field was the last one ever after hundreds of years. The chairman of Box Parish Council, CWB Oatley, proposed that the field be donated to the village and converted into the site of a village hall, but it was not to be.[5] Instead the area was used for residential accommodation and Bargates was constructed in 1950.

Industry was subject to the most dramatic change from military production of arms and munitions to the needs of a post-war population. Moon Aircraft Limited at the Clift Works on Box Hill sought both products and skilled people.[6] The company was wholly owned by the Bath and Portland Stone Firms Limited who had employed their skilled stone masons to make precision plastic mouldings and cockpits for military aircraft.[7] They were the Industry of the Future in 1945, manufacturing peace-time goods out of the newly-discovered perspex into shades for electric lights, soap-trays, fruit bowls and similar with the plastic which, worked like wood, could be turned, sawn, filed and polished.

The Stone Firms never recovered and their demise was swift after the war; their plastics venture never succeeded. By August 1946 a strike of fifty quarrymen at Hawthorn, Pickwick and Box Hill was officially recognised by Transport and General Workers' Union.[8] It was a dispute about wages differentials between unskilled labourers and the stone sawyers wanting an extra 2d per hour. The old order had shifted from piece-rates and the ganger system.

There were changes of personnel also and vicar AF Maltin was replaced by Rev Kenneth Crawford Scott in September 1945.[9]

Equally significant that month was the death of Maisie Gay, announced with the words that she had taken Her Final Curtain at her home at Whirligig, Kingsdown, aged 67.[10] She had run the Northey Arms from 1933 to 1936 and lived in Box ever since, although she was unable to get out much and was bed-ridden for a number of years.

CB Cochran gave his epitaph that in her genre, Maisie was unique and irreplaceable. [11] He had not been able to find anyone since her retirement who was such a wonderful character-drawer. He added a very moving tribute to her that She built a small house at Box and had been in bed ever since she went there. She had periods of unconsciousness and on one occasion when I visited her she wandered right back to her theatre days and said, "Don't worry, Mr Cochran, I shall be ready in time. Her words echoed the sentiment of most Box people during World War 2.

Troop Demobilisation

The troops returned many months after the end of hostilities. Prisoners-of-war were able to write freely but many had been listed as missing and were uncertain whether their families had believed them dead. The government issued instructions (such as the well-thumbed leaflet below courtesy Margaret Wakefield), which possibly added to the anxiety rather than proving a reassurance servicemen and women.

Social Unity or Discord?

We are used to describing the war as a period of great social unity. Commonly-used phrases are Carrying on, Doing Your Bit, and Pulling Together. There is no doubt that there was a common sense of purpose, comradeship and a unity in the face of adversity.

It was partly driven by newspapers, the wireless and cinema, with depictions of English rural life as in Powell and Pressburger's film, The Canterbury Tale. There were certain advantages, employment for all, education of a certain nature, and the chance to visit foreign countries.

Centralisation had many advantages. The Beveridge Report of 1942 spoke of the Five Giants of Need - Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness. A new ideology developed based on fairness, opportunity and full employment, with social welfare and universal benefits regardless of means, including the National Health Service from cradle to grave.

But this was not the whole picture. The war also bred physical hardship and denial and, for some, a desperate need to survive by any means. Panic, youth crime and black market profiteers were commonplace. The difference between self-sacrificing war service and the personal exploitation of circumstances amplified the crimes of some people. In January 1942 a celebrated case of indecency rocked Box, although we might nowadays regard it as rather trivial. Captain Herbert Godfray, aged 47 years, of Rosemary Cottage, Kingsdown, was charged with two others of doing unlawful acts tending to corrupt the mind and to destroy the love of decency, morality and good order.[12] The offense was to post photographs of un-retouched nude studies of models, one a young wife, others of unmarried women aged 16 to 22 years old - models known as Hilda, Joan, Joyce, Marjorie and Eileen. Godfray had served in the Great War and afterwards lost an arm in a motoring accident. He had a wife and three children.[13]

He was jailed for 20 months.

Box in June 1945

The country had been changed for ever by the war. It turned from a free-market economy to a centrally-managed state, perhaps the most centralised in all Europe. Local government was almost eliminated with the reduction of localised hospitals, local Education Authorities and the influence of county magistrates.

Social attitudes had also shifted. In June 1945 the Family Allowances Act awarded money to mothers, the first such award in Britain which did not go to the male head of the household. There was more opportunity for women to work but this was reduced when servicemen returned in peacetime. Servicemen moved extensively over Britain for training, staffing needs and outlying military supplies depots. Many young people left the village of their birth and never returned, whilst newcomers came and stayed.

Society has split over its attitude to the war. Some see the time as their finest hour with victory over the forces of darkness.

For others the period of six years was inglorious, with no poetry, no building epitaphs and remembered now through the prosaic wartime cinema of John Mills in Britain or Hollywood's glorification of events. However, we can all agree with the words of Rev Arthur Maltin in 1945, May was such a wonderful month. The war in Europe is over after five years and eight months.[14]

We are used to describing the war as a period of great social unity. Commonly-used phrases are Carrying on, Doing Your Bit, and Pulling Together. There is no doubt that there was a common sense of purpose, comradeship and a unity in the face of adversity.

It was partly driven by newspapers, the wireless and cinema, with depictions of English rural life as in Powell and Pressburger's film, The Canterbury Tale. There were certain advantages, employment for all, education of a certain nature, and the chance to visit foreign countries.

Centralisation had many advantages. The Beveridge Report of 1942 spoke of the Five Giants of Need - Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness. A new ideology developed based on fairness, opportunity and full employment, with social welfare and universal benefits regardless of means, including the National Health Service from cradle to grave.

But this was not the whole picture. The war also bred physical hardship and denial and, for some, a desperate need to survive by any means. Panic, youth crime and black market profiteers were commonplace. The difference between self-sacrificing war service and the personal exploitation of circumstances amplified the crimes of some people. In January 1942 a celebrated case of indecency rocked Box, although we might nowadays regard it as rather trivial. Captain Herbert Godfray, aged 47 years, of Rosemary Cottage, Kingsdown, was charged with two others of doing unlawful acts tending to corrupt the mind and to destroy the love of decency, morality and good order.[12] The offense was to post photographs of un-retouched nude studies of models, one a young wife, others of unmarried women aged 16 to 22 years old - models known as Hilda, Joan, Joyce, Marjorie and Eileen. Godfray had served in the Great War and afterwards lost an arm in a motoring accident. He had a wife and three children.[13]

He was jailed for 20 months.

Box in June 1945

The country had been changed for ever by the war. It turned from a free-market economy to a centrally-managed state, perhaps the most centralised in all Europe. Local government was almost eliminated with the reduction of localised hospitals, local Education Authorities and the influence of county magistrates.

Social attitudes had also shifted. In June 1945 the Family Allowances Act awarded money to mothers, the first such award in Britain which did not go to the male head of the household. There was more opportunity for women to work but this was reduced when servicemen returned in peacetime. Servicemen moved extensively over Britain for training, staffing needs and outlying military supplies depots. Many young people left the village of their birth and never returned, whilst newcomers came and stayed.

Society has split over its attitude to the war. Some see the time as their finest hour with victory over the forces of darkness.

For others the period of six years was inglorious, with no poetry, no building epitaphs and remembered now through the prosaic wartime cinema of John Mills in Britain or Hollywood's glorification of events. However, we can all agree with the words of Rev Arthur Maltin in 1945, May was such a wonderful month. The war in Europe is over after five years and eight months.[14]

Conclusion

This is not the place to catalogue the extent of the Nazi extermination of six million Jewish people and five million other nationalities. Nor the six million Russian civilians who died as a result of wartime starvation and disease. It was a scale of barbarity not seen since perhaps the Crusades of medieval times, let alone just 70 years ago. There was also the Japanese mistreatment of 60,000 prisoners-of-war and in August 1945 the American nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Box's suffering during the wartime was just a small part of the international story that affected the world.

This is not the place to catalogue the extent of the Nazi extermination of six million Jewish people and five million other nationalities. Nor the six million Russian civilians who died as a result of wartime starvation and disease. It was a scale of barbarity not seen since perhaps the Crusades of medieval times, let alone just 70 years ago. There was also the Japanese mistreatment of 60,000 prisoners-of-war and in August 1945 the American nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Box's suffering during the wartime was just a small part of the international story that affected the world.

References

[1] Donald Bradfield, A Century of Village Cricket, p.64

[2] Parish Magazine, July 1944

[3] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 23 February 1946

[4] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 9 March 1946

[5] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 18 August 1945

[6] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 27 October 1945

[7] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 22 December 1945

[8] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 31 October 1946

[9] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 8 September 1945

[10] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 15 September 1945

[11] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 22 September 1945

[12] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 31 January 1942

[13] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 7 March 1942

[14] Parish Magazine, June 1945

[1] Donald Bradfield, A Century of Village Cricket, p.64

[2] Parish Magazine, July 1944

[3] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 23 February 1946

[4] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 9 March 1946

[5] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 18 August 1945

[6] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 27 October 1945

[7] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 22 December 1945

[8] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 31 October 1946

[9] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 8 September 1945

[10] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 15 September 1945

[11] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 22 September 1945

[12] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 31 January 1942

[13] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 7 March 1942

[14] Parish Magazine, June 1945