We have been asked why we started the late Victorian period at 1870 when nothing much happened in Box that year. But nationally the changes introduced in 1870 were fundamental to the story of Box. That was the year of William Foster's Education Act, which opened a new beginning for the children of Box village. This article deals with the social impact of the school on the village. A fuller history of Box Primary School can be seen on the school's website.[1]

Box Schools Before 1870

Various schools existed in Box and Ditteridge before 1870; some were day schools, some boarding. The largest school was the Charity School in Springfield House (see below) and there were several others: a dame school (often day-care run by well-meaning ladies in their home) for infants in Townsend Cottage and another at Henley; a ladies school at Middle Hill run by Miss Mary Pictor (possibly a Methodist school as the quarry-owner family were dissenters); a church school at Ditteridge; and a Commercial and Boarding Academy run by JV Watts in 1862.

The charity school which had been run in Springfield House by the Mullins family for a century after the 1750s had badly run down. It was described as a tall old-fashioned, factory-like building with 70 boys and 70 girls. It took many fee-paying children and when the charity commissioners visited in 1834 they demanded an increase in the free places from 30 to 50.[2] The Church Rambler reported that the charity schoolroom was in a ruinous condition. After the 1870 Education Act the charity school was brought to a close, the land and assets being sold in 1879 for £2,250.

Various schools existed in Box and Ditteridge before 1870; some were day schools, some boarding. The largest school was the Charity School in Springfield House (see below) and there were several others: a dame school (often day-care run by well-meaning ladies in their home) for infants in Townsend Cottage and another at Henley; a ladies school at Middle Hill run by Miss Mary Pictor (possibly a Methodist school as the quarry-owner family were dissenters); a church school at Ditteridge; and a Commercial and Boarding Academy run by JV Watts in 1862.

The charity school which had been run in Springfield House by the Mullins family for a century after the 1750s had badly run down. It was described as a tall old-fashioned, factory-like building with 70 boys and 70 girls. It took many fee-paying children and when the charity commissioners visited in 1834 they demanded an increase in the free places from 30 to 50.[2] The Church Rambler reported that the charity schoolroom was in a ruinous condition. After the 1870 Education Act the charity school was brought to a close, the land and assets being sold in 1879 for £2,250.

The school took in a broad range of children, including orphans from the Poorhouse, nonconformist and fee-paying children (reduced to 1d a week for those who could not afford the full price). The school gave formal religious instruction including a daily lesson by Dr Horlock and enforced strict discipline. Failure to pay attention in church was punished by the learning of additional Scriptures; lying required the cane; incorrigible fidgetiness merited a whipping; pilferage led to one girl holding a slate with the word Thief on it for an hour. By 1868 it had expanded to 124 children, 53 of them were infants many under 5 years but there were too many different headteachers to give continuity with changes in 1864, 1869 and 1870.[5]

Education Act 1870

The need for better education was highlighted by Disraeli's Reform Act of 1867 which allowed almost all male householders to vote, whether they owned or rented their houses. This leap in the dark showed the need for a more literate population who could read the ballot paper and understand the issues.

The Act had high ideals from the start: to bring elementary education within the reach of every English home and within the reach of those children who have no home. Supervised by independent School Boards, the existing Church of England charity schools were brought into the initiative to cover the country with good schools and to get the parents to send their children to these schools. Most parents took pride in educating their children but the Act was resented by some who registered their children as half-timers (half-day scholars) so they could work the rest of the day pulling weeds and thistles from the wheat. At other times we scared birds, tended pigs and worked in the hayfield.[6] For some half-timers school was a chance to rest.

The Act sought to bring good elementary education to children aged 5 to 13 years but there were shortfalls. Attendance wasn't made compulsory until 1880 (even then with exemptions), nor was it free for all until 1891.[7]

Box New Schools 1875

The need for better education was highlighted by Disraeli's Reform Act of 1867 which allowed almost all male householders to vote, whether they owned or rented their houses. This leap in the dark showed the need for a more literate population who could read the ballot paper and understand the issues.

The Act had high ideals from the start: to bring elementary education within the reach of every English home and within the reach of those children who have no home. Supervised by independent School Boards, the existing Church of England charity schools were brought into the initiative to cover the country with good schools and to get the parents to send their children to these schools. Most parents took pride in educating their children but the Act was resented by some who registered their children as half-timers (half-day scholars) so they could work the rest of the day pulling weeds and thistles from the wheat. At other times we scared birds, tended pigs and worked in the hayfield.[6] For some half-timers school was a chance to rest.

The Act sought to bring good elementary education to children aged 5 to 13 years but there were shortfalls. Attendance wasn't made compulsory until 1880 (even then with exemptions), nor was it free for all until 1891.[7]

Box New Schools 1875

|

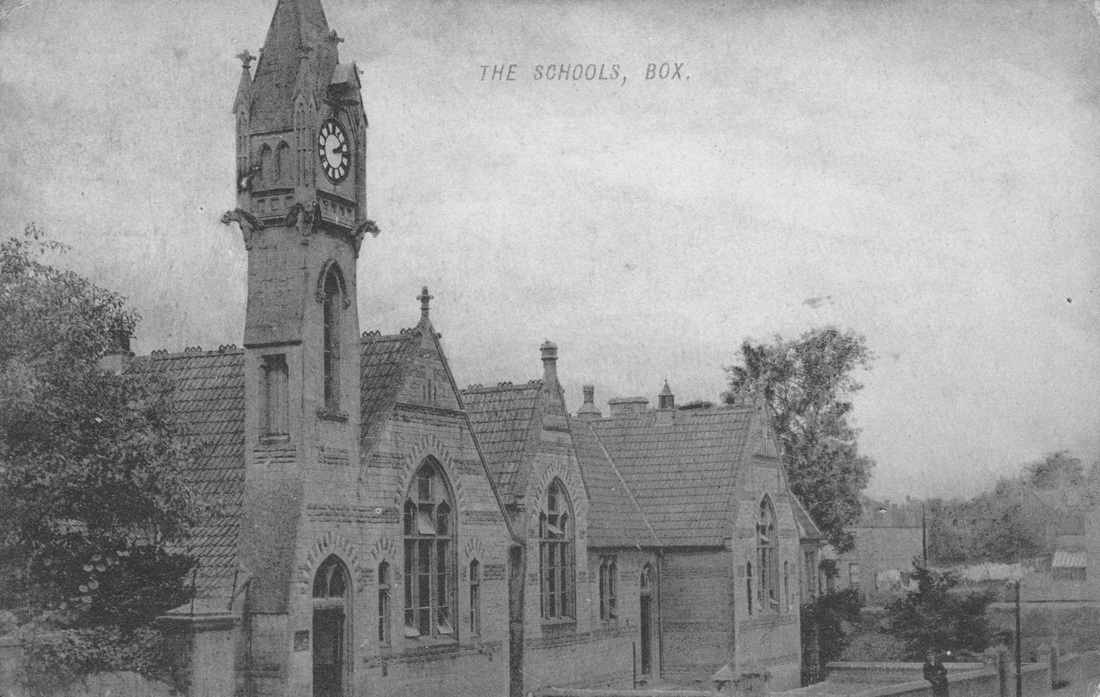

To cope with the Act's requirements Box needed a large school premises to accommodate three different schools: infant, girls and boys. A new building was constructed prominently on the main road in 1874-75 with two projecting wings, one marked Boys Entrance and the other marked Girls and Infants. The sexes were taught separately until they became a Mixed School in January 1924.

It was a prestigious building in a grand Gothic style based on an imposing brick tower, tall, solid and dominating the landscape, designed to demonstrate the village's commitment to the education of its young people. |

It was a remarkably successful initiative offering modern facilities and professional teaching standards supervised by His Majesty's Inspectors of Schools. It is reputed to have opened with a capacity of 400 children but that seems to overstate the capacity.[8] In any event, to cope with demand an extension was built on the school in 1894. When the clock with two faces was installed in the tower in 1897 (at a cost of £62 as part of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations) it reinforced the importance of the building to the life of the village. And later there were more building works reported in the Parish Magazine of August 1914 as: The structural alterations to the Schools have been on so extensive scale that we have been obliged to hold the Sunday School at the Bingham Hall during this month.

Originally the whole system was based on payment by results; grants of 12s per pupil were paid to schools for pupils who achieved the required standard each year up to Standard VI and this was closely monitored by the Schools Inspectors. This led to cramming and restriction in subject-matter, with schools being a factory producing a certain modicum of examinable knowledge.[9]

This system was abandoned in 1890 in favour of capitation grants to the school and even 3d per week (school pence) paid to certain parents to encourage them to enforce attendance.

Education at Box School

The first subjects taught were very basic: reading, writing and arithmetic, taught by rote with virtually no concern for life-skills.

It was later that class subjects (geography, history and needlework) were adopted and in 1890 new subjects (cookery, physical education and woodwork).[10]

Originally the whole system was based on payment by results; grants of 12s per pupil were paid to schools for pupils who achieved the required standard each year up to Standard VI and this was closely monitored by the Schools Inspectors. This led to cramming and restriction in subject-matter, with schools being a factory producing a certain modicum of examinable knowledge.[9]

This system was abandoned in 1890 in favour of capitation grants to the school and even 3d per week (school pence) paid to certain parents to encourage them to enforce attendance.

Education at Box School

The first subjects taught were very basic: reading, writing and arithmetic, taught by rote with virtually no concern for life-skills.

It was later that class subjects (geography, history and needlework) were adopted and in 1890 new subjects (cookery, physical education and woodwork).[10]

Conclusion

We need to remember that the purpose in much of this elementary education was to produce literate clerks, artisans and girls for domestic service but not much more than that. Contemporaries often recall their education at school as being restrictive, repetitious and of no practical use.[12] This was realised and in 1902 the School Boards were abolished in favour of County Councils and Local Education Authorities aiming to provide an education as a ladder from the elementary school to the university.[13]

The 1870 Act had dragged elementary education in Box up to a basic level but it was shown up as wanting. It failed to adequately address the needs of nonconformist children and consequently the Methodist Hall and school classrooms (now called Ebenezer Chapel) were built in 1907 to cater for dissenting children.

Nor was the Act a total success nationally. The Boer War revealed that half the young recruits were physically unfit for war service. Schools were encouraged to provide for the whole person with medical inspection of children (1907); playing fields and swimming lessons (after 1918); better meals and free milk (after 1940). There was much still left to do: Secondary schooling was not adequately reformed until the Education Act of 1944; education for women still requires improvement in certain subjects; education for the disabled waits to be fully resolved between mainstream and specialist schooling. The Act was a start of a struggle to raise standards that will probably never be attained.

We need to remember that the purpose in much of this elementary education was to produce literate clerks, artisans and girls for domestic service but not much more than that. Contemporaries often recall their education at school as being restrictive, repetitious and of no practical use.[12] This was realised and in 1902 the School Boards were abolished in favour of County Councils and Local Education Authorities aiming to provide an education as a ladder from the elementary school to the university.[13]

The 1870 Act had dragged elementary education in Box up to a basic level but it was shown up as wanting. It failed to adequately address the needs of nonconformist children and consequently the Methodist Hall and school classrooms (now called Ebenezer Chapel) were built in 1907 to cater for dissenting children.

Nor was the Act a total success nationally. The Boer War revealed that half the young recruits were physically unfit for war service. Schools were encouraged to provide for the whole person with medical inspection of children (1907); playing fields and swimming lessons (after 1918); better meals and free milk (after 1940). There was much still left to do: Secondary schooling was not adequately reformed until the Education Act of 1944; education for women still requires improvement in certain subjects; education for the disabled waits to be fully resolved between mainstream and specialist schooling. The Act was a start of a struggle to raise standards that will probably never be attained.

References

[1] See several interesting articles at http://www.box.wilts.sch.uk/index.php/history

[2] John Ayers, A Christian & Useful Education, Wiltshire History Centre, p.26

[3] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, The Downland Press, p.62

[4] John Ayers, A Christian & Useful Education, Table VI

[5] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.65

[6] Alfred Williams, In A Wiltshire Village, 1981, Alan Sutton, p.11

[7] http://www.educationengland.org.uk/history.html

[8] See http://www.box.wilts.sch.uk/images/publications/History/Extractsfromschoollogbooks.pdf

[9] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750-1965, 1979, Wayland Publishers Ltd, p.56

[10] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750-1965, p.51-52

[11] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750-1965, p.101

[12] See Stella Clarke article

[13] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750-1965, p.80

[1] See several interesting articles at http://www.box.wilts.sch.uk/index.php/history

[2] John Ayers, A Christian & Useful Education, Wiltshire History Centre, p.26

[3] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, The Downland Press, p.62

[4] John Ayers, A Christian & Useful Education, Table VI

[5] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.65

[6] Alfred Williams, In A Wiltshire Village, 1981, Alan Sutton, p.11

[7] http://www.educationengland.org.uk/history.html

[8] See http://www.box.wilts.sch.uk/images/publications/History/Extractsfromschoollogbooks.pdf

[9] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750-1965, 1979, Wayland Publishers Ltd, p.56

[10] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750-1965, p.51-52

[11] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750-1965, p.101

[12] See Stella Clarke article

[13] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750-1965, p.80